Artificial Intelligence is in the headlines. Human civilisation at risk, at one extreme; unrivalled advances in cancer treatment at the other. An international letter had been circulated, asking for ChatGPT to be paused while nations debate it.

Grappling with the rapid rise of AI was the issue for debate in one recent group discussion.

“I tried out chatGPT at work last week” was Julie’s way into the subject. “We need to know what makes a good policy on student withdrawals in our university” she explained. “The programme searched a range of universities for such policies, then summarised and analysed them. The result was pretty good. It has its uses, but we know it can be biased and misinformed” she added.

Marian had heard an interview which pointed out how “AI can come up with beautiful things. It has the potential to free people up”. “But it’s not making ethical decisions, is it?” she added. What mystified Sarah was why the result of a complex digital process seems to be “more than the sum of its parts”. “How does AI learn?” Marian wondered. “Good question … and how do we learn ourselves, anyway, biologically speaking?” added Patrick.

Before exploring the topic, we need to look carefully at the meaning of the “I” word in AI. The concept of “intelligence” (outside its military use) is not well defined. Long before computers entered the fray, psychologists have contested the meaning of the word. Some believe there is a “general” intelligence factor in humans that can be measured in IQ tests. Others believe there are many types of intelligence. In common parlance it’s often used to characterise disparate qualities, such as memory capacity, extreme skill, academic style, command of language and more. For this reason, I find the word unhelpful, not referencing a clear, unambiguous quality. In this blog we avoid the term and explore the fundamentals of how machines and brains learn by processing information and producing outputs.

Digitalisation

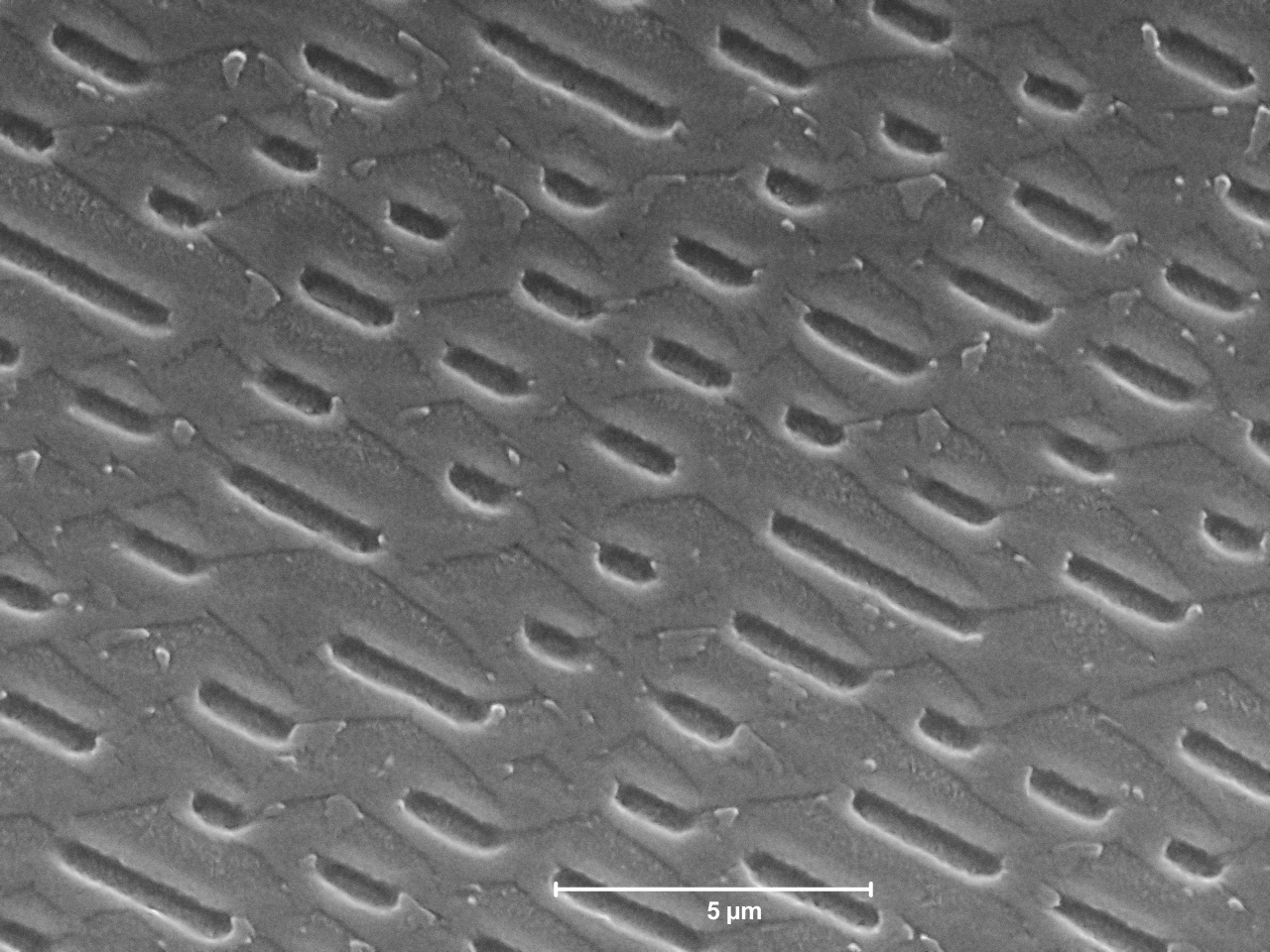

A good starting point is a major transformation we’ve alread got used to, thanks to digitalisation. Enormous amounts of information are routinely stored and reproduced in recorded music, moving images, voice messages and stock market prices, for example – it’s fundamental to the way modern electronic machines work. The process can visualised in a graphical way by comparing microscope images of the tracks laid down in CDs and their predecessors, LPs or “vinyl”.

Figure 1 Grooves on a vinyl record Figure 2 Data pits in a CD (electron microscope)

As figure 1 shows the V-shaped grooves in a vinyl record are tiny wavy lines that fluctuate sideways and up and down. The shape of the wave is analogous to the shape of the sound wave that created them. That’s why the process of transferring the information – the shape of the wave – is known as analogue.

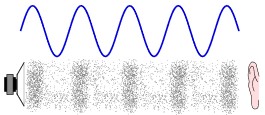

In figure 3 a sound wave is illustrated as a series of compressions in air and the degree of compression is represented in a rising and falling graph.

Figure 3 A sound wave – represented in two ways

In a record player, a sharply pointed needle, or ‘stylus’, follows the shape of the waves, causing corresponding fluctuations in electric current to pass into an amplifier. This recreates the sound wave shape that is impressed into the vinyl.

A CD, on the other hand, has no grooves, no waves; instead, the spiral track consists of a series of short bumps of varying length with flat gaps between (figure 2). A very fine laser is reflected off these bumps, creating a momentary pulse whenever the laser detects the upside or downside of a bump. The electronics interprets a pulse as the digit 1 and the absence of a pulse as a 0. The bumpy track passes under the laser very rapidly. As it does so, a series of 1s and 0s as registered which are interpreted as numbers in the binary counting system. The fast-moving sequence of numbers represents the shape of the sound wave.

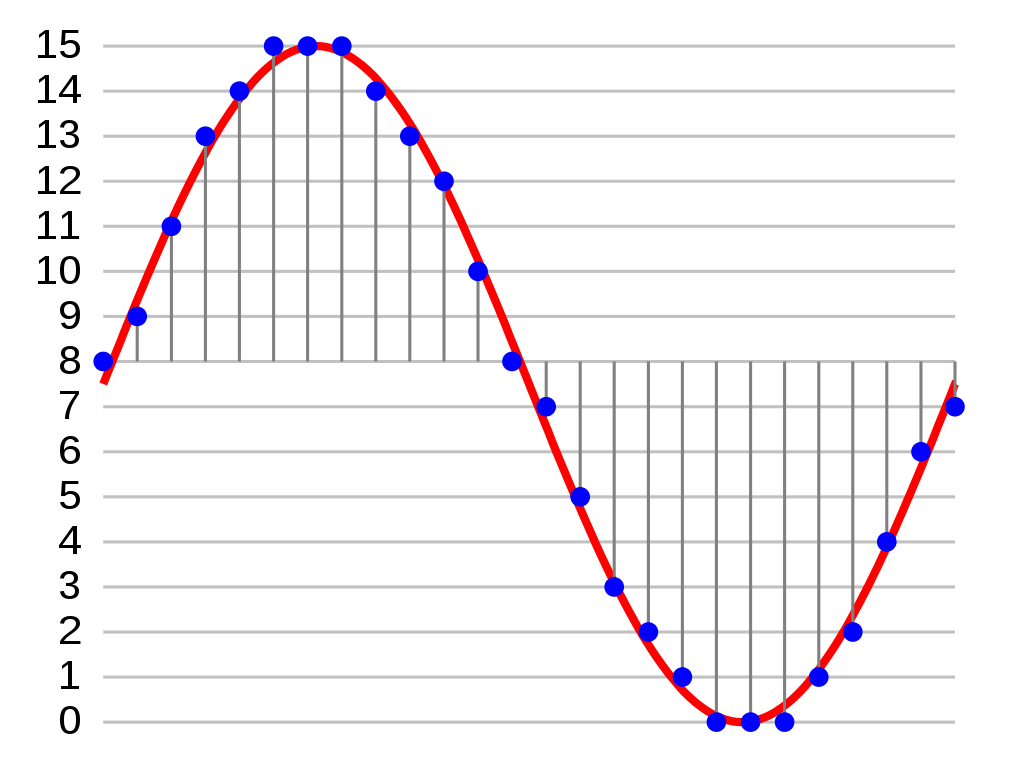

In figure 4, a series of numbers (the height of each blue dot) approximates the shape of a sound wave (red). In this way, a sound wave can be stored in a computer as a sequence of numbers. It’s quite amazing that something we experience as complex and aesthetic as music, can be stored as numerical information on a computer and reproduced at will with minimal distortion.

Figure 4 a wave (red) represented by a sequence of numbers (blue)

The purpose of this dive into CD technology is to remind ourselves how familiar we already are with computers being able to store, interpret and reproduce experiences that we consider deeply human.

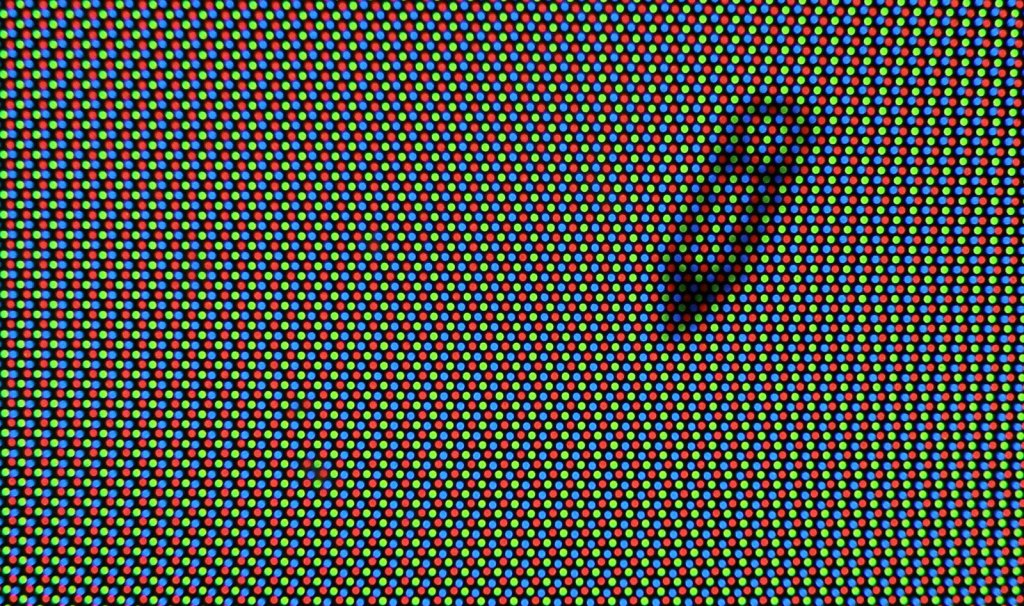

Visual images, as well as sounds, are routinely represented as an immensely long series of digits. Each number in a sequence represents the brightness of a dot of a red, blue or green hue on a television screen, for example (figure 5).

The image on the screen is simply a set of points where the dots are darker than the bright ones around them.

Representing complex things like moving images on the TV or a 60-minute CD of music requires, as you might expect, a huge number of digits. A single CD has several billion bumps – each coding for a binary digit. A typical TV screen has a few million pixels – or coloured dots. Clearly, the capacity of our devices to process images and sounds depends intimately on the amount of storage space they have for digits and the speed at which they can read them. The pace of the digital revolution – from CDs and TVs to AI software – is determined by the rate at which microchips can be miniaturised for this purpose. Artificial Intelligence has developed in recent years because the capacity of computers now allows enormous quantities of information to be processed extremely rapidly.

It is an extraordinary thought, that all the images we see on screens, all the documents that have been produced on computers – from bank statements to the works of Shakespeare – all the music and radio/TV programmes available by streaming are stored in gigantic databases, dotted around the planet. The volume of stored information is simply staggering – and yet it comprises nothing more than enormously long sequences of 0s and 1s, binary digits representing numbers, letters, colours, sounds and more. The total quantity of data in the world is estimated to be in the hundreds of trillions of Gigabytes – and a Gigabyte is a billion bytes (a byte is a group of eight 0s and 1s). It’s an unimaginable number.

The human brain

“How does this kind of capacity compare to that of the human brain?” was the issue raised in one discussion group. “How much information can our brains store?”. “Do they work in similar ways to computers?”

The last of these questions is easier to answer. No; brains work in fundamentally different ways to computers – hardly surprising, given that they are made of living tissue and have evolved over hundreds of millions of years. Like computers, our brains do big numbers: they contain around 100 billion neurons each of which is connected to up to a thousand others – making 100 trillion points of connection, or synapses. But crucially, our brains do not rely on some external entity to tell them what to do. When an infant learns to walk or speak, they are not following a precise set of instructions like a computer. They have a capacity to learn on the hoof. Experience – trial and error – is working alongside their genetic inheritance to shape the way their brain grows. Some capacities are, of course, innate – like the ability to suckle at the breast, to crawl, stand up and make sounds, perhaps even some universal rules of language. But much of our adult ability develops in response to inputs we pick up through our eyes, ears, nose and skin. Our brains process signals from our senses and produce models of the external world that help guide us through it.

Infants learn statistically by detecting repetitions and patterns in stimuli. For example, regularities in the syllables they hear in language enable them to split a spoken stream into separate words; in the visual field, they become aware of the spatial connection between objects and the regular way in which one event follows another. They connect things they see and hear: the link between voices and faces, for example. Studies of infant behaviour show that their learning doesn’t just happen passively in response to whatever inputs happen to be around. Instead, they actively direct their attention to stimuli from which they are likely to learn: they are driven by curiosity. Indeed, it has been shown that they treat the unexpected as an opportunity to learn.

The extraordinary capacities of the brain – to see, feel, think, hear, act – are not properly captured by counting the number of cells or weighing them. The power of the brain lies more in the extent of its connectivity – the number of ways each cell is connected to others. A connected set of neurons is commonly called a network, by analogy with, say, a fishing net or railway network. A fishing net consists of threads tied together in knots; a railway network has junctions at which separate lines meet.

Networks in the brain consist of cells (neurons) with long thin extensions (axons), which correspond to threads or railway lines, and places where they link together (synapses), analogous to knots or junctions. Where a fishing net might have a few hundred threads with just four meeting up at each knot, a network of neurons may comprise millions of neurons, with hundreds, or even thousands, meeting together at each junction – massive complexity!

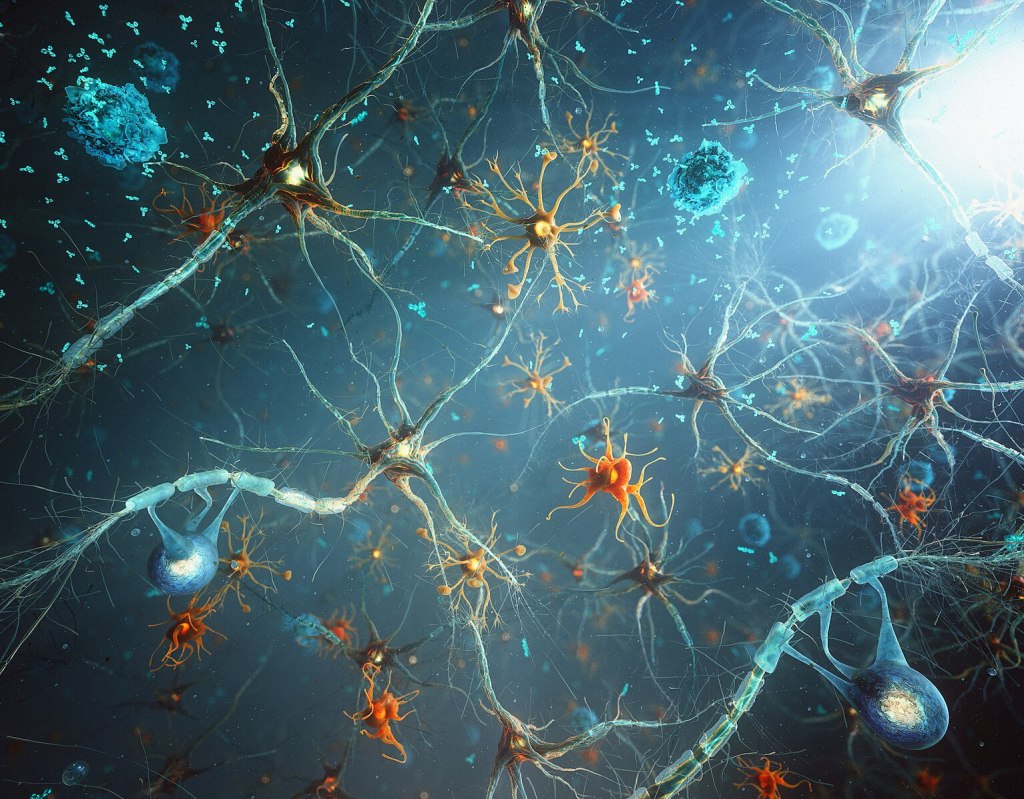

Figure 6 is an imaginative, but simplified, realisation of a network of interconnected neurons (blue/grey) interspersed with another type of brain cell (orange).

Figure 6 various kinds of cell in the brain

Brain activity consists of minute electrical pulses (less than a tenth of a volt) which can pass along the long thin arm (axon) of one neuron and connect with a neighbouring neuron at a junction (synapse). Whether the electrical pulse passes on from one neuron to the next depends on the sum-total of all the pulses arriving at that moment at that junction. Different neurons have different thresholds for ‘firing’ – i.e. passing on the electrical signal. Thus, whether a network gets activated or not in any given situation is a complicated matter, depending on the interaction of very many signals.

Machine learning

The concept of neural networks in the brain began to inspire scientists and engineers around the 1980s. The idea that machines could imitate human actions through coded programmes was much older, of course. Pianos and fairground organs could be made to play automatically, using rolls of punched cardboard.

These relied entirely on a pre-programmed set of precise instructions, encoded in the roll, however, and could not be considered as expressing any form of learning or intelligence.

Insights from neuroscience into how cells in the brain fire off, and stimulate neighbouring neurons to fire or not, offered a new way of thinking about memory storage and learning. With the advent of ever more powerful computers, could the working of the brain inspire the design of new software?

Neural networks

We can easily observe in everyday life one of the ways a brain, as opposed to a mechanical organ, works out what to do next. When an infant starts finding their way round the world, no programme is feeding in coded information, no external trainer is issuing instructions. The child is trying out possibilities, making mistakes, estimating how far wrong their errors are. In this instinctive trial-and-error process, repetition is the key. By taking note of sights, sounds and points of contact in each repeated attempt, then judging which is closest to the desired outcome, the naïve brain gradually learns. Specific sounds gradually become associated with particular meanings; forces that make things fall or remain in balance get understood; pressures and itches that hurt are recognised.

This capacity, to learn without instruction, is the idea behind ‘artificial neural networks’, an important innovation in the way machines learn – the very basis of ‘Artificial Intelligence’.

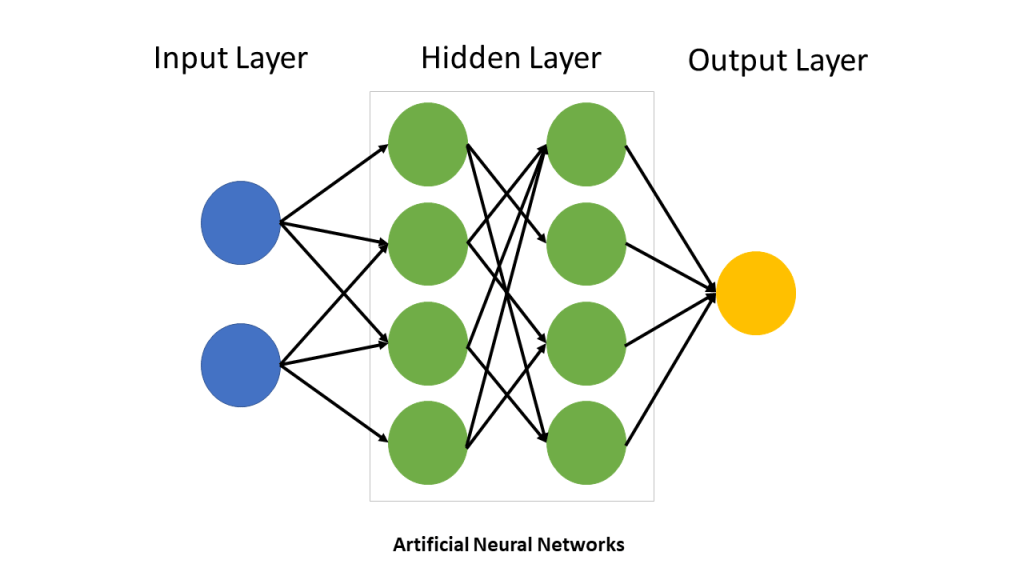

Taking inspiration from the way neurons are interconnected in the brain, the artificial version comprises a huge number of nodes (coloured blobs in figure 7) – effectively on/off switches – which are linked to one another in layers.

Figure 7 simplified model of an artificial neural network

The input layer (blue) is linked to a large number of sensors or other sources carrying electrical pulses from a visual image, a sound, a series of numbers or a piece of text. The diagram shows just two for simplicity.

These are linked to all the electronic switches (transistors in a computer) in the first hidden layer (green). Each of these may or may not transmit a pulse (known as ‘firing’) depending on whether the sum total of all the pulses it receives from the input layer add up to a sufficient value (a ‘threshold’). In addition, when it does fire, a certain ‘weight’ is assigned to it (randomly at first), making the outgoing pulse weak or strong.

Pulses from all the first layer of switches that did fire, strong or weak, then pass to all the second layer (green). Again, the sum-total of the strong and weak pulses reaching this second hidden layer of switches may or may not be strong enough to trigger each switch in this layer. Those that do, send their outgoing pulses to the final layer, which represents the output of the network. This will again be a set of numbers representing an image, a sound, a piece of text or some kind of spreadsheet of numbers, depending on the use the network is being put to.

Repetition is the key: on a first run-through, the values of the thresholds and weights attached to each node (or switch) are often randomly assigned. As a result, the output will be a random image, text string or sound. The software then compares this output to models it is designed to emulate, such as scans of cancerous tissues or data on investment decisions. The (training) image, or sound or text used as input will produce a set of values of the various thresholds and weights associated with each node in the network. These are noted and the difference from the random ones generated by the network are calculated. These are the ‘errors’ resulting from the first trial. These are used to correct the thresholds and weights in the network and the process is repeated. The errors will be less the second time around. Further repeats of the cycle, gradually minimise the errors until a point is reached where the output of the network closely resembles the training model used initially. This method is called, appropriately enough, ‘supervised’ learning.

Now the network has ‘learned’ the set of values to associate with each node in the network, when, say a cancer scan is the subject. The training is finished, and the network can now be used indefinitely, with its learned set of values, to assess whether a new scan, from a new patient, is close to the cancerous model ones. A similar approach enables essays, music, artwork or other form of communication to be modelled.

Another distinct type of machine learning dispenses with the need for training material. Instead, in this so-called ‘unsupervised’ learning, the input information is analysed for inherent patterns within itself. For example, in the process known as ‘text mining’ a set of documents on a given theme may be analysed to work out the grammatical structure of the sentences – where the nouns, verbs prepositions and conjunctions are, for instance. From this, clusters of words that serve similar roles or have analogous meanings may be clustered together. The frequency with which each particular word is followed by, or preceded by, another particular word is calculated, over many sample documents – thousands or more. The construction of relevant sentences can then be guessed at using probabilities based on the large samples.This is probably how ChatGPT managed to produce the feasible policy document for Julie, mentioned above. .

Machine learning is more widely used already than one might think. We have begun to get used to machine responses to telephone enquiries, train announcements and loudspeakers you can talk to. Instant text translation is now available for a huge number of languages. Further explanation of how these work is given under Further Information below.

Artificial Intelligence

The above processes describe important ways in which machines can be said to learn. The processes involve either initial training of the software and/or pattern-seeking in data without training. However, the loose way in which words such as learning, intelligence, pattern and training are increasingly being used to describe these machine actions, drives us to check a little more carefully what we mean by them. What is happening in the brain when we learn, train ourselves or recognise a pattern? What does the concept of ‘intelligence’ actually mean? Is AI adopting these words legitimately or are we being misled by them, for dramatic effect?

The word ‘artificial’ doesn’t present a great problem. It is define- by the Cambridge dictionary as being “made by people, often as a copy of something natural” – a useful reminder that AI is made by us humans! The word “intelligence” is more slippery. It’s defined in the same dictionary as “the ability to learn, understand, and make judgments or have opinions that are based on reason”. This emphasis on ‘reason’ appears to leave creative and artistic ability out on a limb, as well as sincere religious beliefs. The widespread idea of “IQ” (Intelligence Quotient) gives an impression of a definable and measurable thing: a number that can be assigned to individuals, on the basis of a standard test. The application of this is a matter of debate in psychology. More on IQ and other theories of intelligence is in the Further Information section below.

It seems to me that the word ‘intelligence’ is unhelpful in the context of AI. It neither steers us towards a clear understanding of the capabilities of machines that might be helpful nor, more importantly, to those that might be damaging. Is the concept of ‘learning’ any more useful? Do the similarities and differences between this capacity of humans and machines take us forward?

Learning

We have already introduced the idea of ‘machine learning’ above, in discussing the way artificial networks, inspired by networks in the brain, can be trained to undertake helpful tasks, such as translating between languages or analysing medical images. A respected psychology resource describes learning as:

“a relatively lasting change in behaviour that is the result of experience. It is the acquisition of information, knowledge, and skills.”

Learning is, of course, not restricted to the formal type, developed for schooling, involving instruction and observation. We are all learning continuously, from the first time we touched a hot plate to the last time we chose a mobile (cell) phone. Pets and other animals learn too, for example, by associating their owner with food (Pavlovian conditioning) or by learning how to sit, after being repeatedly rewarded (operant conditioning). Anyone who has learned a foreign language or a musical instrument, trained in sport or learned to drive knows that repetition is key to learning. Routine daily practice may seem boring to a child, but it has been shown to underlie success in acquiring expertise in all sorts of areas – from virtuoso piano playing to touch typing.

Brain science is beginning to explain biologically how skills and memories are acquired. The basic elements of a brain circuit – neurons – connect together to enable actions and thoughts to occur and for memories to be stored. We now know that when a cell ‘fires’ – i.e. transmits a pulse to another, connected, one – it also, in the same act, slightly strengthens the specific connection (synapse). In this way, connections that are repeatedly used, become stronger over time. In effect, a highly strengthened network of connections constitutes a long-term memory. With sufficient repetition, the associated actions become automatic – as any experienced driver knows.

In this respect the process of learning in machines seems to have significant similarities with the analogous process in the brain. The actions within artificial neural networks bear a resemblance to those in biological ones – repetition strengthens connections. A major difference however, which is giving concern to experts in the field who are looking ahead, is the question of capacity. The development of ever smaller microchips is enabling computers to store ever larger amounts of data and to cycle through their operations at ever faster speeds. It is these capacities, to hold on to vast amounts of data and process it rapidly, that enables a machine to look in greater detail at a medical scan or parse a much larger number of sentences than a human brain. And these capacities are growing steadily.

Given their phenomenal memory capacity and lightning calculation speeds, it’s understandable why computers are now able to outwit exert chess players. It’s reasonable for commentators to speculate about what other types of expertise these growing powers will soon make redundant. This seems to me to be a legitimate cause for concern. It’s also important, however, to think about what the anticipated rise in computing capacity will not able to achieve – which aspects of human brain functioning machines will not be able to replicate.

Innate capacities

Long and drawn out though our human childhood is, other animals seem to jump into life’s routine almost immediately. Lambs spring into life within minutes, needing no time to learn the art of walking or gamboling. Healthy, new-born human babies make straight for the breast without instruction and recognise the mother’s face within a few days of birth. So clearly, unlike a computer, human brains come ready equipped with plenty of vital information that doesn’t have to be learned afresh. One study estimated that it would take a child one year of asking questions for it to match the extent of training a computer system uses to analyse images. So how do animal brains (including our own) achieve such phenomenal feats of manipulation and thought without the speed and capacity of a modern computer. The same study explains that brains, far from working everything out by trial and error in the present moment, are drawing instead on hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary experience. During this time, billions and billions of individuals, over countless generations in our ancestral species, have developed patterns of brain networking that help them survive and reproduce. The gradual development of ever better adapted circuitry is passed on from generation to generation, from species to species down the evolutionary tree, though the information encoded in their DNA. More detail on the evolution of brain circuitry and DNA is in the Further Information section below

Conclusion

Drawing comparisons between machine learning and the action of networks of neurons in the brain vastly oversimplifies the complexity of brain functioning as a whole. The activity of neurons is influenced by the insulating layer of myelin with which they are partly covered. Other types of brain cell than neurons also play a role. Electromagnetic waves oscillate throughout the brain in different ways at different times, signalling, for example, the various phases of sleep. So, there’s much to find out about the way the brain works in all its functions, and the extent to which artificial processes will overtake it. Machines have no conscience, no emotion, no preferences of their own. We have limited understanding of how these and other aspects of human functioning are represented in the brain.

Looking to the future, many commentators point to the beneficial effects that the capacity to store and rapidly process vast amounts of data will bring – enhancing medical diagnosis, refining business processes, streamlining factual learning, increasing food production, for example. But equally, some on the forefront of research and development are warning of the potential dangers. Enhanced facial recognition and ever more convincing false information could pose a threat to democratic processes; greater accuracy in targeting missiles or financial systems could upset the international order. Clearly, these forward-thinkers will be aware that machine learning will be exploited by criminals and warmongers as well as by well-intentioned public servants. Such has been the case in previous examples of rapid technological advance. Developing a regulatory framework to monitor and constrain misuse, on a world-wide basis, will be as important as ever.

The purpose of this blog has been to elucidate some of the baffling principles behind the AI revolution, and to relate the novelty of it to things we are already familiar with. The question of how it turns out to affect our lives and those of our children and grandchildren is unpredictable. Let us hope that promoting the potential of AI for the benefit of humanity, while protecting it from the threats, becomes a high priority for world leaders and international bodies in the coming era.

© Andrew Morris 12th July 2023

Further information

IQ and other theories of intelligence

The origin of the idea of a measurable general intelligence – the basis of the IQ test – is the statistical observation dating back to the early 20th century that people who score highly on one type of cognitive test, say maths, tend to score highly on other kinds of test, say in language. Psychologists at the time invented a number known as the ‘g factor’ which quantifies the correlation between two or more given tests. The theory is that this correlation implies the existence of a ‘general’ intelligence, independent of subject area, that varies between individuals. Roughly half of the difference in test scores between individuals is put down to this “general intelligence” factor.

Other, later psychologists have suggested alternative theories that several different kinds of intelligence exist – such as musical, interpersonal or bodily (kinaesthetic). The American Psychological Association concluded in 1995 that “no concept of intelligence ….. commands universal assent. Indeed, when two dozen prominent theorists were recently asked to define intelligence, they gave two dozen, somewhat different, definitions.”

Language translation

One option for the design of translation software is to deconstruct the grammar and syntax of the given text and apply rules of the target language to reconstruct equivalent sentences. Errors sometime occur. An alternative method uses the statistical approach outlined above, in which the probability of a particular word being followed by another specific one, in any given context, has been worked out through training on huge numbers of existing texts. Google’s translation software, for example, uses this approach and was trained using approximately 200 billion words from United Nations materials.

Software that understands the spoken word – such as the machines that try to direct your phone call by analysing your voice responses – are based on similar approaches as those used for translation, First, noise and background sounds are filtered out, then the sound wave is digitised, converting its up and down pattern into a long series of numbers. The resulting speech pattern is then broken down into the short, basic units of speech, known as phonemes and known probabilities are used to guess the most likely phoneme to follow any given one. An alternative approach makes use of a trained neural network, with its trial-and-error, method to rapidly cycle through successive approximations till it is good enough – all done in the microseconds before you’ve moved on to the next phoneme!

Evolution of brain circuitry

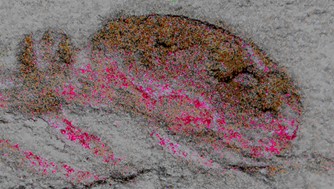

Figure 8 is the fossilized head of a 525-million-year-old arthropod, named C. catenulum. It contains the earliest known brain strcutures, indicated by the magenta-coloured deposits.

Figure 8 The earliest known brain

The discoverer says “We have identified a common signature of all brains and how they formed. Each brain domain ..[is] .. specified by the same combination of genes, irrespective of the species. –[There is] a common genetic ground plan for making a brain.” Not only have brain structures been remarkably conserved over evolutionary time, but so has DNA itself, Organisms from bacteria to humans all have the same DNA system.

This extreme consistency in DNA and brain structure over time means animal brains today are endowed with coded instructions in their DNA that specify networks to be built into the brain as it develops in the embryo. When we humans, and other animals, are born, we already have highly sophisticated capacities wired into the brain. Of course, like a sophisticated AI machine, we have lots to learn from experiences, too – and we humans have a particularly extended childhood for just this purpose. But, in contrast to a machine, we inherit a vast amount of our capability at birth, thanks to our genes AI software has to do the best it can to make up for the lack of 500 million years of evolutionary knowledge!