Discussion took off one windswept evening, after heavy rainfall had flooded part of the UK. Wendy, a member of the discussion group, living near the Ribble estuary had noticed her district had escaped the flooding, despite being close to a major river.

“Perhaps it was because the soil was particularly sandy where I live” she conjectured. Another member of the group, Patrick, had been attempting to walk along a footpath across fields in Sussex, but had got bogged down in sopping wet clumps of grass. Same weather, different soils.

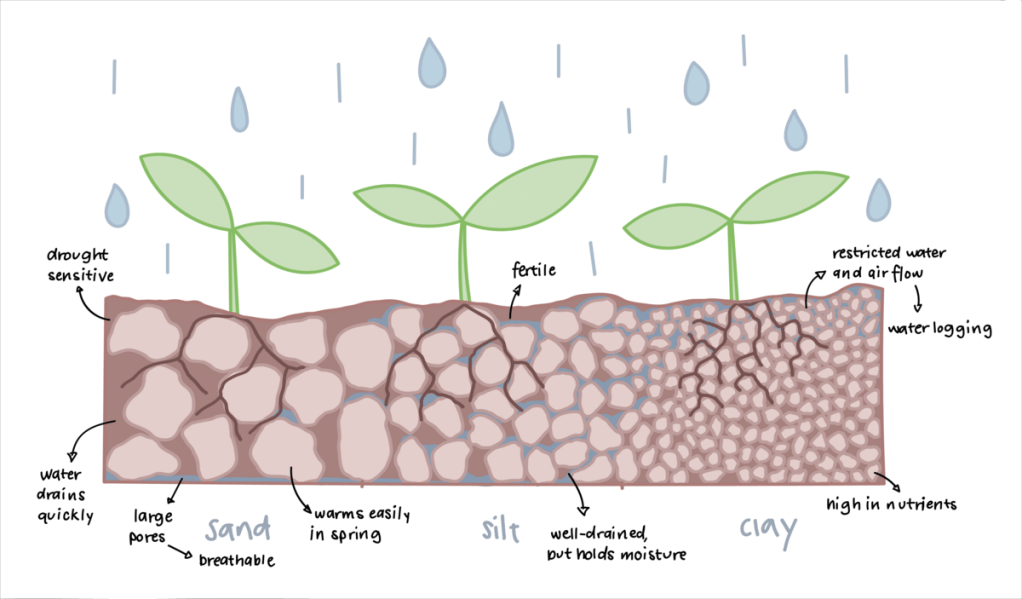

Wendy’s conclusion was that it must be that the sandy soil in her district was absorbing the water, while the clay soil in Sussex was doing the opposite. This hunch is borne out by the distinct geology of the two areas. As figure 1 illustrates, sandy soil is composed of relatively large particles, compared to the smaller grains of clay soils.

Figure 1 Comparing sandy and clay soils

This results in wider channels for the water to flow through in sandy soils, enabling flood water to be taken up more easily. The permeability of soil is affected by other factors too. Channels for water to flow through are also created by organisms in the soil such as the thread-like mycelia of fungi and tunnels created by burrowing worms and ants.

Absorption is actively researched in countries most seriously affected by flooding. A study in Aceh, Indonesia shows the rate is influenced by the texture, organic matter and structure of the soil. Research in China shows that moisture and plant roots play a part in grasslands. Compaction of the soil, caused by tillage or trampling by animals, emerges as an additional factor according to research in Ethiopia.

Ideas about mitigating the threat of flooding were introduced by people in the group. Jean described a scheme in the area of London where she lived, in which wetlands were to be restored, stretches of rivers slowed down and new areas of natural drainage created. Storage ponds are to be built, trees and hedgerows planted, and agricultural practices altered to improve soil structure to increase water absorption.

Patrick recalled hearing that drainage systems overflowed more frequently these days because less and less rainwater was being absorbed into the earth, as a result of the proliferation of hard surfaces in urban environments.

Helen explained that this was the purpose of new grid-like structures that were now being used to provide a hard standing for cars, for example. Spaces between the lines of hard material allow surface water to be absorbed into the underlying soil.

Figure 2 Hard standing that allows rainwater to be absorbed.

She pointed out that, “with London built on clay, the warmer weather was causing the clay to harden in summer, exacerbating the run-off of rainwater” – an example of how a small change in climate conditions is able to cause significant disruption.

Rivers

The natural course of many rivers has been altered, over time, to suit agricultural and urban development. Concrete channels and dams have been introduced, flood plains cut off, and river courses straightened in places. Although this may suit farming and housing development locally, it can also cause severe flooding and loss of wildlife downstream. As a consequence, river authorities, in some areas liable to flooding, have taken action to restore river courses. An example is in Cumbria where repeated flooding, in towns such as Carlisle and Cockermouth, has led to new meanders being built into straightened reaches of a river and floodplain barriers being removed. As a result, the flow of water is slowed down and excess is stored in a floodplain, saving downstream towns and villages from sudden surges after heavy rainfall. Improvement in water quality also encourages fish and other species to return, thus restoring the ecosystem. This video clip explains all.

Mention of meanders jolted Helen into recalling something of her school Geography lessons – “meanders and oxbow lakes … I remember”.

It’s not hard to see how an extreme meander, as in figure 3, might eventually lead to the river carving out a short cut across the narrow peninsula, straightening its course and leaving a small oxbow-shaped lake where the meander once was.

Figure 3 Meander in the Auvergne region of France.

The flow of water at a sharp bend will inevitably mean the material of the bank gets attacked when the current is strong. The bank is gradually eroded, exacerbating the curvature of the bend. Debris created in this way will be deposited on the bed of the river on the opposite side, where the current is weaker.

Figure 4 erosion and deposition at a river bank

Recollecting geography lessons many years ago, Jean recalled that the course of rivers changes gradually due to this kind of erosion, ultimately carving out whole valleys over geological time. Helen thought about the silt that results from the debris created by erosion. As she recalled this can make the surrounding land very fertile when it is deposited after flooding. Early civilisations developed around rivers such as the Nile and the Tigris and Euphrates, as a consequence of the prosperity brought by bountiful farming.

Intrigued by this, Helen asked about the flow of water in a steam: “is it consistent across its width or throughout its depth?” At a bend, it seems obvious that it doesn’t, just by looking at a reiver or stream.

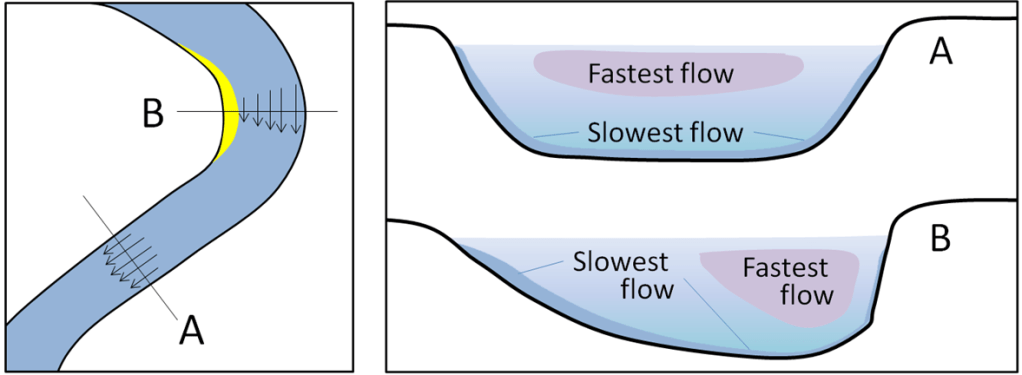

The speed is slower on the inside of a curve, just because it has less far to go. This is illustrated in figure 5 at position B.

Figure 5 varying speed of flow in a river

But what about a straight stretch of river? Again, just by looking carefully next time you are at a riverside, the current is usually slacker by the banks and faster in the middle. This is illustrated at position A in the figure. Friction, where layers of water rub against the static material of the bank and the bed, slows down the flow.

Fluid dynamics

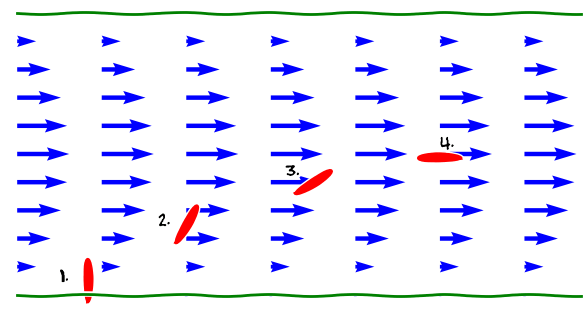

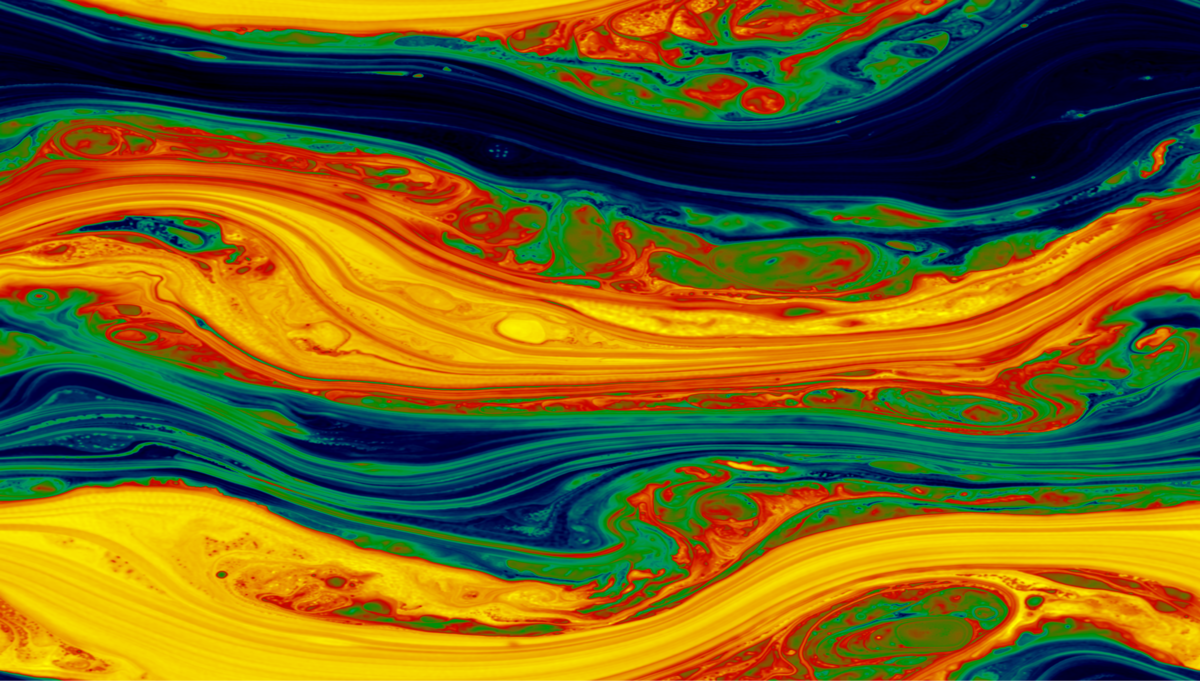

Imagine the layer of water closest to the back or riverbed – it barely moves, due to the frictional effect of the solid matter. The layer next to this moves a little faster and the next a bit faster still.

Figure 6 Varying speeds across a flowing liquid

These layers will slip past each other easily, so long as the speed is not too fast and the liquid is slightly viscous (as water is).

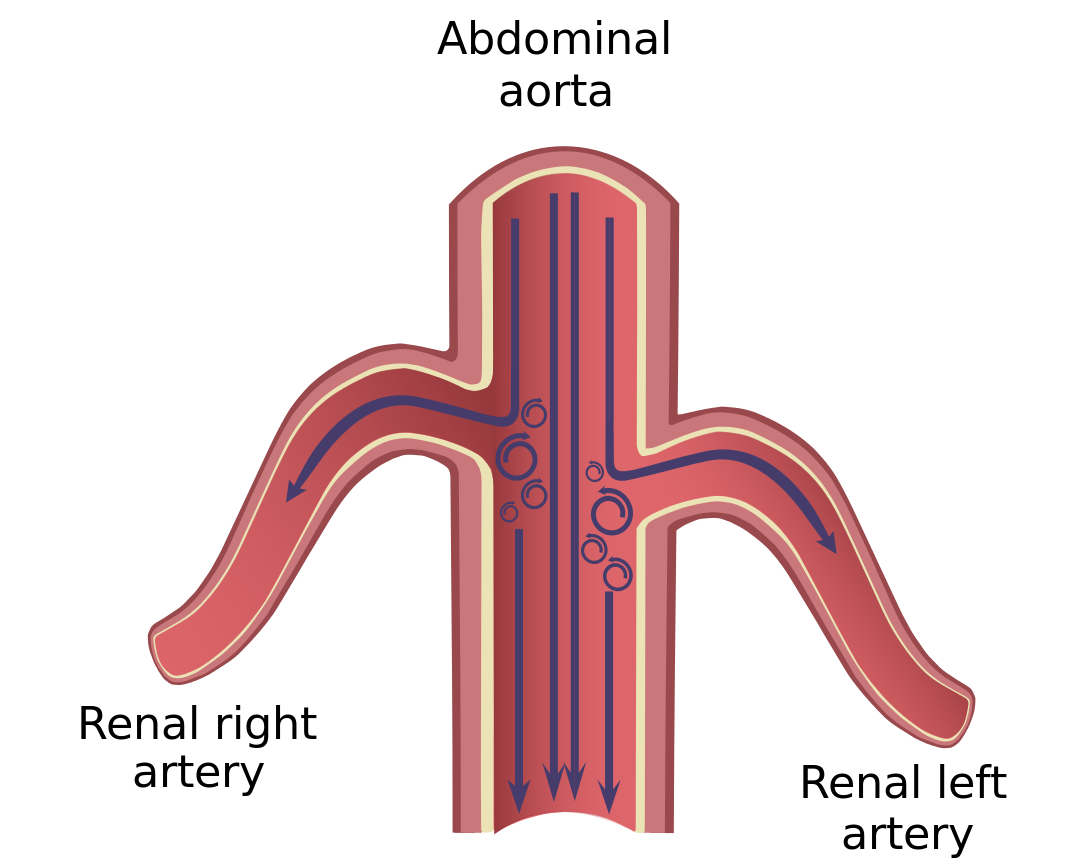

This situation is what is required if oil is to flow smoothly through pipes, blood through arteries and air over aircraft wings. In this condition, known as laminar flow, there is no sideways mixing between the parts of the flowing fluid. If, however, the flow is too fast or the fluid insufficiently viscous, sideways (lateral) forces will cause adjacent layers of the fluid to mix. The result is a breakdown of the smooth laminar flow and the outbreak of turbulence. Lateral forces across the flow are now superimposed on the forward forces driving the flow, causing pockets of fluid to spin around – the effect we see as eddies in a river, or feel as buffeting when an aeroplane encounters turbulent air.

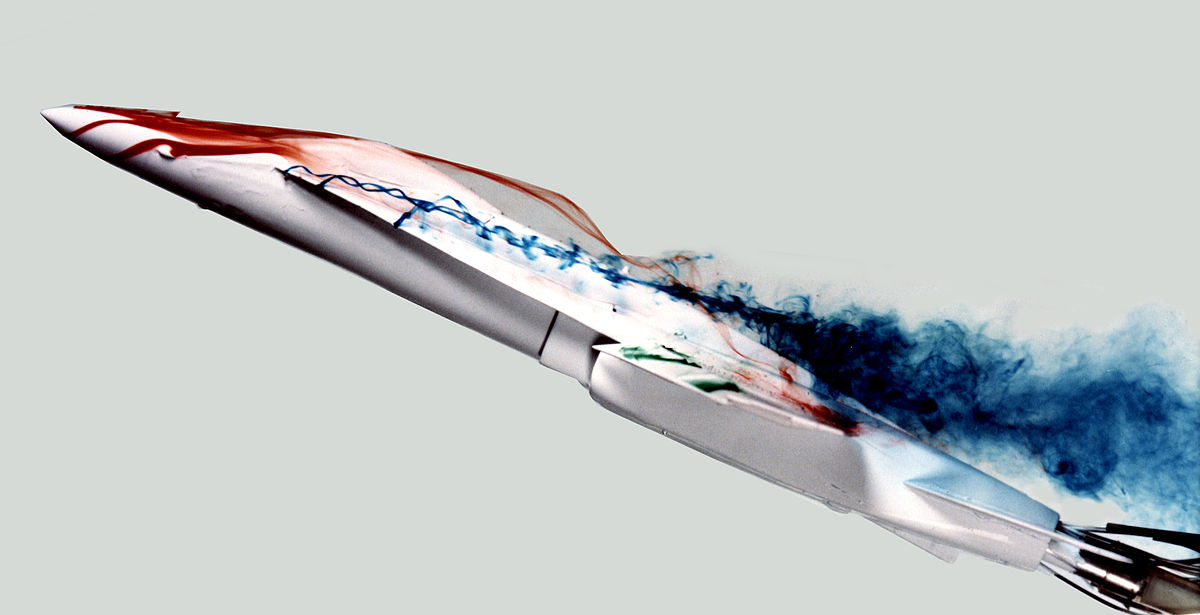

The study of flowing fluids is known as fluid dynamics. Despite its low public profile as a field of science, it is of immense significance in many areas of life. Not only are the distribution of water, oil and gas dependent on understanding of flow, but the ventilation of hospital wards, circulation of blood, distribution of pollen and safe manoeuvring of aircraft all depend on it. The difference between laminar and turbulent flow can be of vital importance, as the illustrations in figure 7 show:

Figure 7 Turbulent flow in blood vessels, aircraft and magnetic fields around a black hole

But it was to none of these fields that conversation turned in the discussion group. Instead, the meaning of the word ‘fluid’ was discussed: “a substance that has no fixed shape and flows easily” according to the dictionaries. Liquids are an obvious example, but gases, including the air, follow the same patterns of flow, too. Less obvious are the gels, cream and lotions so common in medicine and cosmetics. Jean had recently been to an exhibition on Beauty at the Wellcome Collection in London. It illustrated how “beauty products are designed so they spread properly” . Mention of beauty products sparked a quick reaction from Wendy. “I’ve always doubted whether commercial beauty products you rub on your skin are actually absorbed, as the adverts claim. Do they really flow?” she queried.

Creams and lotions

Mention of creams and lotions triggered discussion about the various emollients and barrier creams we put on our skin. Do they count as fluids? What do they do?

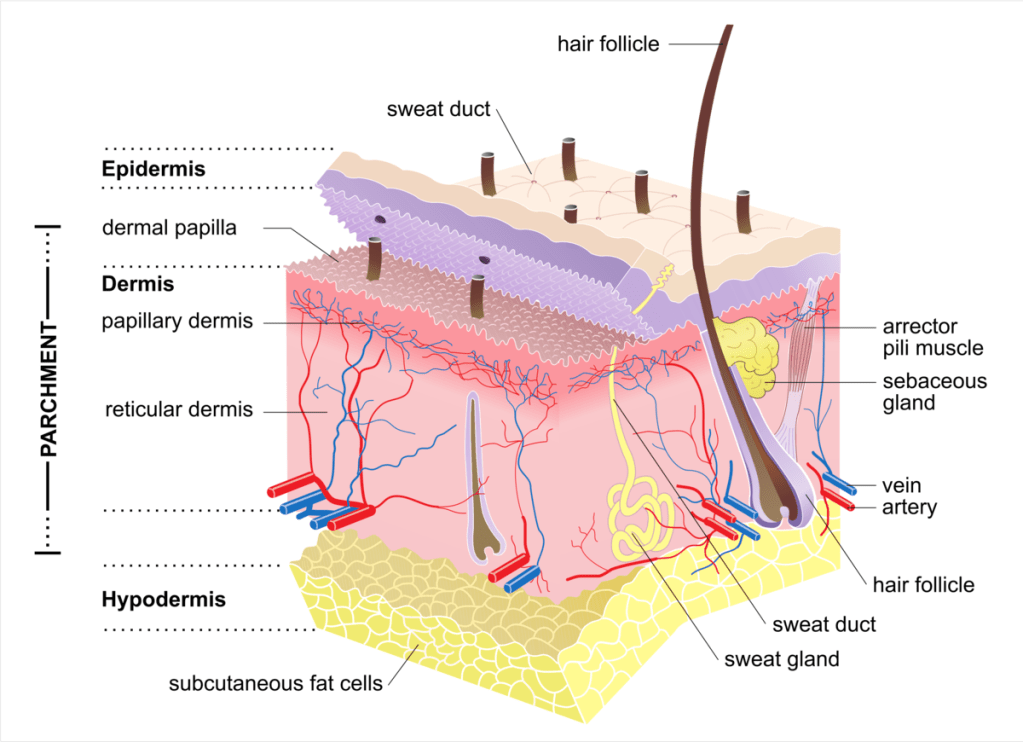

They are indeed fluids because they too flow just as liquids and gases do, however slowly this may be. Helen imagined the ‘barrier’ as a way of preventing moisture in your body from passing out through your skin and evaporating. She was right: water evaporates constantly through the skin. A certain dryness is needed on the outermost layer of the skin, to enable cells to die and be shed gradually, removing dirt and bugs as they do so. On the other hand, some moisture is needed in the deeper layers to prevent the skin lower down becoming too brittle. Skin cells migrate upwards from the deeper layers of the skin, ending up as dead cells on the surface. Here they mesh with oil-loving molecules in a network, forming a barrier that enables the body to regulate its moisture content.

Moisturising creams are useful as an adjunct, when natural regulation fails. One type creates a coating of water-repellent molecules, to prevent loss of water from within. A different type, comprising the opposite kind of molecules – water-loving – draws water molecules into the epidermis – either from the outside air or from deeper layers in the skin. The various words used for cosmetics or medicines applied to the skin define different formulations of these opposing ingredients. Ointments are 80% oil and 20% water; creams are 50% of each and lotions are even less oily.

Wendy had contested whether cosmetic formulations were actually absorbed by the skin, as the advertising claimed. It turns out they certainly can be, though not all do. Different kinds of “cosmeceutical” modify the skin in different ways. Moisturisers simply increase the water content in the outer layers of the epidermis, by one means or another. Anti-ageing products, in addition, may also penetrate through to deeper skin layers. Some simply hydrate the outer layers, plumping them up and reducing the prominence of wrinkles. Others include supplements, such as fragments of the protein collagen, which reinforce the deeper layers of natural collagen that give skin its elasticity. This can be helpful as we age because natural collagen molecules become less abundant and less elastic Such supplements can be administered by rubbing a cream into the skin or taken as pill; trials have shown the treatment can be effective. The ability of molecules to penetrate through the layers of skin does vary, however: only molecules below a certain size can fully penetrate the skin according to recent research. Natural collagen molecules are larger than this so cosmetic treatments use smaller broken-down fragments that are able to penetrate to the deeper layers.

Whatever the route of administration, or the purpose, absorption into the skin is mainly through a process of diffusion through the spaces between the skin cells of the outer layer – the epidermis.This space is filled with lipids – oil-loving molecules – through which the equally oil-loving molecules in ointments, creams and patches diffuse easily.

Figure 8 Layers of skin and their components.

Some may also be absorbed by direct transmission through the hair follicles and sweat ducts; but, as these are relatively few and far between, this is a relatively minor route.

The active ingredients of medical creams continue to diffuse downwards from the epidermis into the dermis layer below. This tissue contains tiny blood vessels (capillaries, shown in red and blue). Molecules from a medical cream then diffuse through the walls of the capillaries, into the bloodstream. From here they are able to circulate throughout the body, just as medicines in pills or injections do. They then get picked up by the receptors at which the are targeted – nicotine or oestrogen receptors throughout the body, for example.

Fluid dynamics

Having established that ointments, creams, lotions and gels are all examples of fluids, subject to the same tendency to flow as water or air or any other liquid or gas, Wendy was keen to get back to the physics of flow.

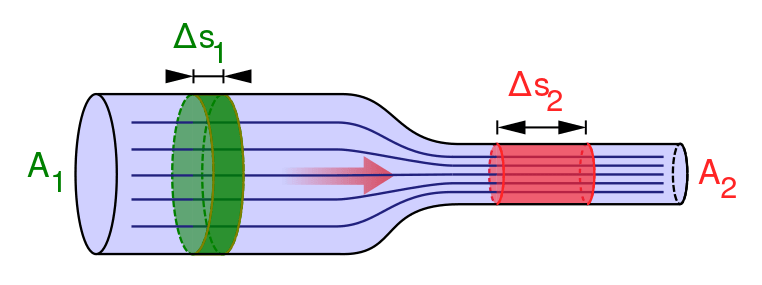

The simplest concept – obvious as soon as you think about it – is that the amount of fluid that flows past a point each second must be the same everywhere. It’s called the principle of continuity. You can’t have less fluid flowing in one place than another or it would have to break up into discontinuous bits.

This has the obvious implication that fluids must speed up when they are constrained in a narrower space (red), in order for the same quantity to get through, each second, as in the wider space (green).

Figure 9 fluid flow through a narrower space.

This idea is intuitively simple, but it has a much less intuitive consequence. If the fluid flowing from the wider section speeds up, there must be a force making it do so. In other words, there must be greater pressure in the slow-moving section accelerating the fluid into the fast-moving section. I always had difficulty getting my head around this idea at school– it seemed more intuitive to me that the pressure would be the same everywhere in a flowing fluid.

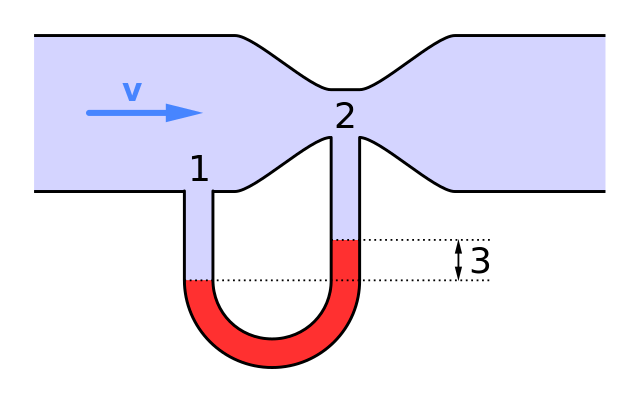

Figure 10 shows the different pressures graphically. At 1 the pressure is higher where the speed is slower, the reverse is true at 2. The difference is shown at 3.

Figure 10 differing pressures in slow and fast moving fluid

You can experience this yourself by holding two sheets of paper close to each other but apart, then blowing between them. They draw together as the pressure between them drops. If you pass a flat hand through water in the bath or swimming pool, you may even feel it lift up slightly. This is an example of the aerofoil effect, where fluid has to travel faster over a longer distance on the topside of an aerofoil then on the underside. Figure 11 illustrates the effect of air passing over an aerofoil or wing.

On the left-hand side, the vertical line of black dots separates at the leading edge of the wing, It then travels faster over the longer distance of the upper surface. You can see the dots are more thinly spaced on the top.

Figure 11 Aerofoil effect – an aircraft wing

As a result of this higher speed, the pressure drops on top below that underneath. The wing lifts.

The flow of fluids is thus fundamental to our understanding of aircraft design. It is also essential in architecture to ensure buildings are adequately ventilated and that warm or cool air reaches all parts as required. Study of fluid flow proved especially important during the pandemic when the transport of virus particles on breath, when people got too close, or in hospital wards were infections could easily spread, became a matter of life and death.

Even less visible than air flow is the flow beneath the streets of the vital fluids that keep our buildings and vehicles supplied with oil, gas and water. Not only do these have to be piped smoothly over hundreds or even thousands of kilometres, they also have to be distributed locally. Once they’ve reached our homes and businesses, they have to be carefully conducted into nozzles in the burners of our boilers or hobs, to ensure a smooth, uninterrupted flow.

For oil, water and gas to pass steadily through their pipes, sometimes uphill, sometimes down dale, they have to be pumped up to higher pressure at the source end, from whence they flow to the lower pressure area where they are used. This reflects one of the simplest and most intuitive rules of fluid dynamics: that fluids flow from regions of high pressure to lower pressure. Not only does this underlie the way vital fuels are transmitted around the world, it also explains much about our weather. Wind is simply the movement of air masses from high pressure regions in the atmosphere to lower ones (modified by the spin of the Earth). Thanks to heat from the Sun the air in some regions is more pressurised than in others.

Conclusion

Fluid dynamics – the science of moving fluids – is clearly a central concern of fuel engineers, building designers, agronomists and meteorologists. It’s also of increasing importance in public policy as we deal with issues of climate change, energy security and infection control.

This blog has followed closely the path of a real discussion with people who enjoy thinking about the natural world. As it is based on things each of them has noticed in their daily lives, the thread has moved in unconventional ways. What started as an observation about rainwater soaking away in sandy soil, soon moved on to schemes for restoring river and wetlands. An imaginative leap then led to other examples of absorption – medicines and cosmetics through the skin – and, ultimately to the principle of fluid flow that keeps aircraft aloft. In effect, an interesting collection of observations from everyday life, linked together through discussion, opened-up an important area of physics and engineering: fluid dynamics. Although, there is a lot more to the subject – especially the complexities that arise when flow becomes turbulent – this set of observations serves as a vivid introduction to the subject.

© Andrew Morris 9th March 2024