Beautiful images of remote galaxies such as this launched a mind-blowing discussion between two science groups and the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Catherine Heymans. She had pipped her English counterpart to the post by becoming the first female Astronomer Royal in the UK in 2021.

In an hour long Zoom discussion, Catherine outlined the basics of her special interest in dark matter and the group pitched in with questions and comments about a topic that had intrigued them for many years.

The launch of the very latest telescope, named after another female astronomer, Vera Rubin, was the topical starting point. After 10 years of construction its first images had just been released, in July 2025. This telescope, with its unrivalled primary mirror, camera and data processing capacity, has an ambitious mission: to scan the entire sky, once every three days. In this way it will build up over time a series of images capable of revealing changes as they occur anywhere in the visible universe. Eventually they will form a kind of slow movie of our cosmos, with one frame every three days. Because of this, it’s expected to pick up changes that we don’t ordinarily manage to capture. You’d have to be extremely lucky, after all, to spot the explosion of a supernova or transit of a random asteroid unaided: just by chance looking in the right direction at the right moment. These practical possibilities for the telescope are important for attracting funding support and media attention; but, for the hardcore astronomer, the big excitement is about what it is expected to throw up about the dramatically named “Dark Matter”.

Jean was quick off the mark with the obvious first question: “what exactly is dark matter? We keep hearing about it, but it just sounds like some fictional stuff out of Star Wars?” As Catherine pointed out, it doesn’t help that the name is misleading: it’s matter, but it isn’t dark …. it’s misnamed, like so many scientific terms. Dark things, like black clothes, absorb the light that falls on them, so don’t reflect any back to your eyes. That’s the meaning of darkness: absence of light. This mysterious kind of stuff is really ‘translucent matter’ because light just passes straight through it; it doesn’t absorb light or indeed interact with any kind of radiation. Rays just pass through it; and that’s unusual. Light is always absorbed to some extent by the matter we are familiar with, even by clear glass – just try looking through three of four sheets of it stacked together.

“Ahh, but if we can’t see it, and it doesn’t interact with anything” Sarah interjected “how can we possibly know it’s there “. Good question – and it’s why it’s only very recently that we’ve come to realise that there must be dark matter. Studies of the size and nature of the universe as whole, and how it has been evolving over billions of years, have pointed to a dilemma, that dark matter resolves. The universe as a whole is held together by the gravitational pull between all its component parts – the stars and planets and interstellar gas, all attracting each other. But when calculations are made of all the observable matter in the universe, the total mass is far too small to provide enough gravity to hold it all together: spinning galaxies, for example, would have been torn apart centrifugally because gravity is be too weak to hold them together. The clear and totally surprising conclusion was that there must be lots of other mass around everywhere, that we just don’t see. What’s more, to satisfy calculations about holding the universe together, the amount of dark matter must make up around 85% of the total mass in the universe. Whatever it is, there’s a lot of it about – and it’s absolutely everywhere, not just out in remote galaxies.

With theoretical speculation dating back to the 1930s, that huge quantities of dark matter must actually exist, the hunt was on for a way to find it, to measure it, despite its invisibility. An ingenious way was found. It had been known since Einstein formulated his theory of gravitation (aka the General Theory of Relativity) that distance and time across the universe are not in fact laid out in imaginary straight lines as we’d expect from our everyday experience of travelling, and the passing of time, here on Earth.

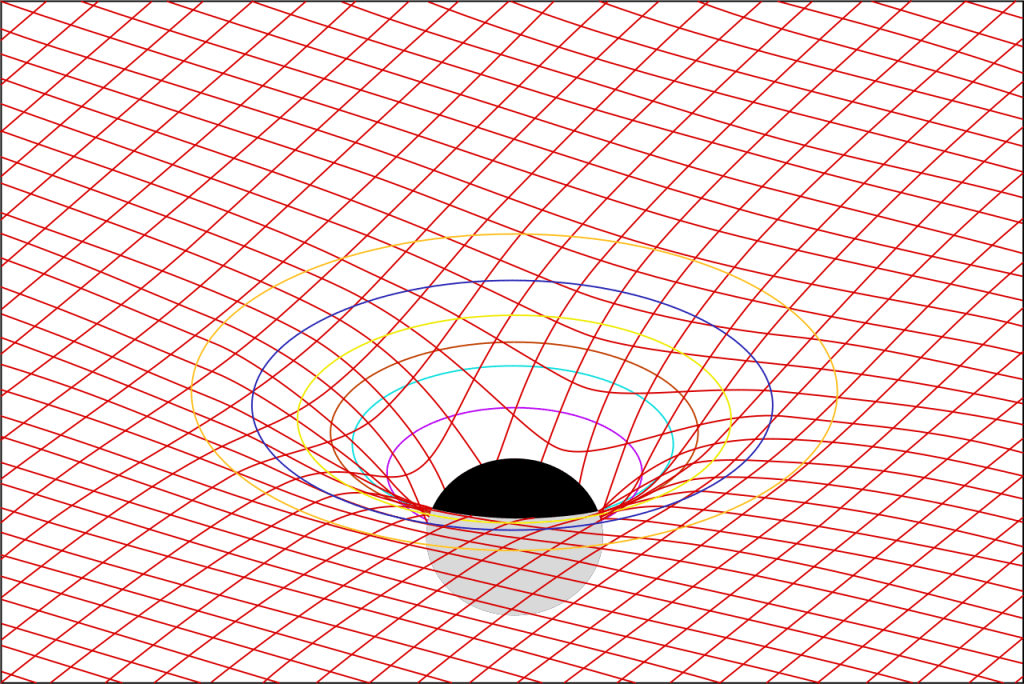

We are accustomed to east, west, north and south forming a perfect grid with right angles at each corner. Einstein’s theory showed that where there is mass, the lines become curved, and this becomes noticeable wherever the mass is large – like a massive star or galaxy. Figure 1 illustrates how this distortion looks, at least in the analogy of a two dimensional surface like a trampoline. The full 3- D reality of curved space is impossible to visualise.

Figure 1 Spacetime curves where there is a mass

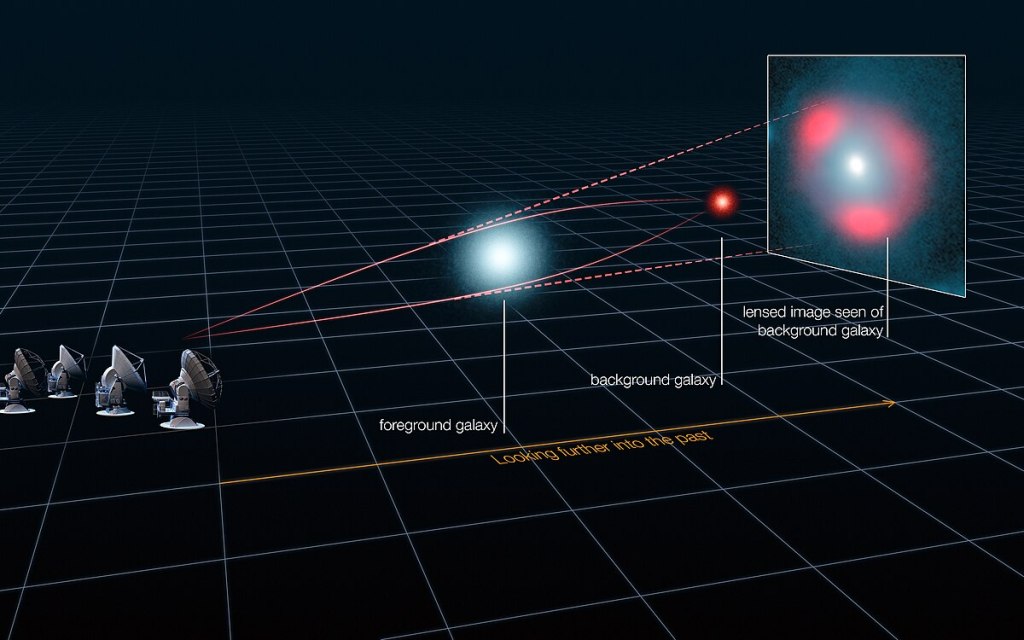

It was later realised that any rays of light passing along the lines of this warped grid would naturally follow the curve. So light shining from a distant star or galaxy beyond this warped zone would be bent, as illustrated in figure 2.

The human eye or a telescope here on Earth would see the light from a distant star, that lies behind an intervening massive object, seeming to come from places around the true position. See figure 2.

Figure 2 Warped spacetime bending the path of a light ray

This is because the foreground galaxy distorts the grid of spacetime causing the light rays from the real star position to follow a curved line. Our eyes and telescopes, however can only infer that light travels to them in a perfect straight line; so we see the starlight appearing to come from positions all around the true position. This is what astronomers can now observe – multiple images or rings or smeared out images from stars lying beyond a massive object like a black hole or galaxy.

Extrapolating this idea to full three-dimensional space, we can imagine a whole ring of false star positions caused by the warping of spacetime in all three dimensions by the black hole.

Figure 3 shows a galaxy, in edge-on view, in the foreground passing in front of a distant star or galaxy causing the light from it to spread out temporarily in a ring as it passes by. Light spread out like this around the true position of the source can be seen in photos taken through powerful telescopes.

Figure 3 A foreground galaxy bending the light from a galaxy behind it

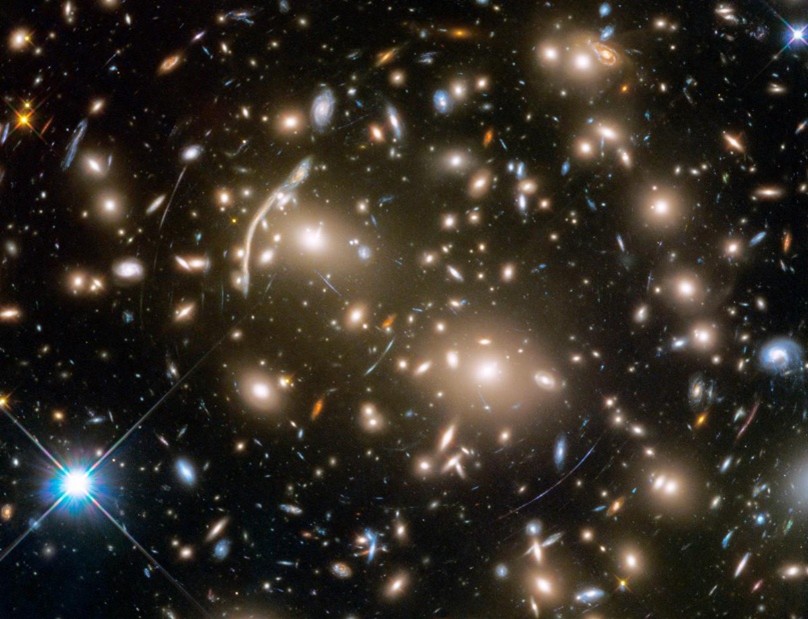

The photo in figure 4 shows light from very distant stars appearing to be spread out in arcs, rather than just being points. This spreading implies that a heavy mass must lie in the middle of this image. By measuring this distortion, the strength of the warping of spacetime caused by the dark matter can be deduced.

Figure 4 Light from a distant galaxy bent into arcs by intervening dark matter

“Amazing” said Wendy at this point, “But is the nature of dark matter literally unknown?” she queried. “Yes” responded our astronomer “there’s definitely something out there that affects gravity, but we don’t know what it is like; or just possibly our whole theory of gravity could be wrong!” she added provocatively. What astronomers are now trying to do, she continued, is to try to catch particles of Dark Matter somehow – but no one has succeeded yet.

“Is it really all around us and passing through us?” asked Sally, somewhat incredulously. Yes indeed was the reply – “but this is not an entirely new concept. We’ve known for many decades about another particle, called a neutrino, that also just passes straight through matter without interacting”. Seventy million of these tiny particles pass through you in one second. A group of scientists in Italy is trying to catch one of these incredibly elusive particles by housing a giant vat of liquid deep inside a mountain called Gran Sasso, in the hope that the mountain itself will help slow down a neutrino enough that it will leave its mark in the liquid detector. To try the same approach to stopping a dark matter particle, scientists in the USA have built a detector in an old mine, one mile deep, using a large vat of Xenon to catch a particle in. Unfortunately, it failed to detect a single one. Now, a group of British scientists is building an even more powerful detector deep in an old salt mine in darkest Yorkshire, on the coast at Boulby. It will be bigger than the US one, containing 60 tonnes of Xenon (six times more), which it is hoped will be enough to stop a DM particle one day.

Galaxies

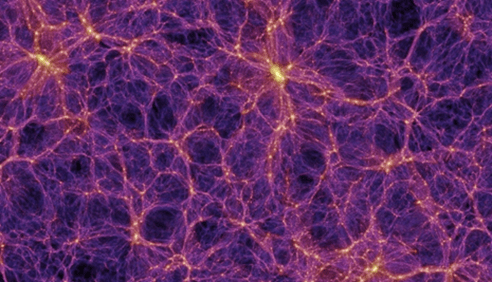

Jean in the discussion group had seen beautiful images from the recently launched James Webb telescope, which is orbiting our Earth, showing that distant galaxies appear to be arranged across the universe in threadlike filaments, rather than just dispersed evenly. See figure 5.

Figure 5 billions of galaxies strung out in long thread

She had heard that maybe dark matter is the cause of this kind of structure. It’s true, dark matter is thought to be at the heart of this filament type of structure. In between the filaments there is a remarkable paucity of galaxies – these pockets are more or less voids. The voids are created because matter tends to be attracted to other nearby matter by gravity, so any slight unevenness in the spread of matter will become more pronounced as matter clumps together, leaving emptiness behind. The contrast between voids and filaments is so extreme, however, that there must be lot more gravitational pull than the visible galaxies alone could provide. A lot more invisible mass must be present to create such fine filaments and empty voids; dark matter must be shaping the superstructure of the galaxies.

Helen, who has always been fascinated by the nature of gravity, asked a more fundamental question: “why does matter create gravity?” Catherine agreed this was indeed a profound question. She described gravity as “how we perceive the curvature of spacetime”. So, the big question is: does mass curve spacetime or does curved spacetime create mass?” As so often in science, “why” questions cannot be answered. That’s for philosophy or religion to struggle with. Science sticks to observing and measuring in order to generate theories capable of predicting behaviour. It‘s good at ‘what’ and ‘how’, but less good at ‘why’.

Dark Energy

The final section of the discussion with Catherine Heymans led to an even more mysterious concept: the existence of Dark Energy (DE). Having established back in the 1920s that the universe is not just a static collection of stars but is constantly expanding everywhere, a more recent discovery, in the 1990s revealed that this expansion is not only happening, but is gathering pace all the time: it’s accelerating! It was an American astronomer Edwin Hubble who showed that every star we see is in fact moving away from us. He deduced this from his observation that the colour of the light from stars was redder than expected. Likening this ‘redshift’ to the shift in pitch of a receding ambulance siren (the “Doppler” effect), he realised that distant sources of light must be speeding away.

The more recent observation in 1998, that the universe is accelerating as it expands, demanded further explanation. There must be something pushing against the inward pull of gravitational attraction, to account for this. Without knowing what it is or how it works, scientists have inferred the existence of a new kind of energy throughout the universe. The name says it all – dark energy. Our astronomer, Catherine confirmed “we know nothing about it – perhaps it’s not even energy; maybe our whole framework of physics is wrong?” But we have to imagine it to explain how the universe, far from imploding under gravity is, unexpectedly, ‘exploding’; something unknown is driving it outwards. Let’s dub it dark energy!

Conclusion

This encounter with a leading astronomer gives us a glimpse into one of the most baffling challenges of our age. Can it really be true that everything we humans have worked out about the universe in which we live only applies to 15 % of the universe? Are we really immersed in a shower of particles that pass through us, undetected and unidentified? Will even more powerful instruments finally detect these predicted particles? Or will our theories just have to change? Thinking about the cosmos in this way can seem very abstract, perhaps even pointless. As people in the group put it: will there be any benefit from these studies of dark matter? Is it really worth spending so much public money on these vast telescopes and particle detectors? Why do scientists pursue these esoteric enquiries?

The sheer enthusiasm of Catherine Heymans and her unmistakable fascination with her chosen topic was enough to answer these questions. Some individuals do just get gripped by deep mysteries, and become determined to delve into them, come what may. Antarctic explorers, cryptic crossword solvers, astrophysicists – it seems to be an aspect of how we humans are constructed. Curiosity is universal in infants and doesn’t seem to discriminate much between useful and useless quests, at least initially. I think we have to accept that some individuals, somewhere, will be motivated to pursue almost any conceivable avenue of enquiry.

But will the quest for dark matter or energy be useful, will it be worth it? It’s a tricky question to answer. A common view amongst scientists is that the ultimate usefulness of basic research is completely unpredictable. Many discoveries of fundamental importance in our lives originated as the wild, imaginative pursuit of some mystery. Quantum theory began as a dramatic departure from accepted truth in one great act of imagination, unrelated to any practical application; yet the insights it has since provided underpin the subsequent discovery of semiconduction and hence electronics, computing and digital communications. The invention of the microscope was hardly intended to open up an unimagined world of tiny living things – the bugs that would transform our understanding of disease – but it did.

So-called “blue sky” or basic research is undeniably important, and some has to be pursued without concern for any subsequent application. The world of science and technology, applied to pressing human problems is, however, equally important. The issues is: where to draw the line – and who should draw it? Super powerful telescopes and giant particle colliders need to be built on an ever grander scale to unearth the next generation of discoveries; but their costs also become ever grander. The replacement for the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Geneva is currently estimated as seventeen billion dollars. How do you balance this against the benefit of advances that could be made with that level of expenditure on research in medicine, climate change or mental illness? You can’t, not scientifically at least! It takes broad, democratic decision-making to arrive at some kind of consensus between competing ideas; these choices go to the core of our humanity and have to be made in the light of all aspects of what makes us human. My guess is that societies will stumble on indefinitely, reserving some fraction of their carefully audited expenditure for wild and apparently purposeless probing of our surroundings, even in the face of justifiable pressure for immediately useful innovations.

© Andrew Morris August 2025