Mining for ‘rare earths’ is set to be part of the peace process in Ukraine. Rising demand for unusual metals has become a major geopolitical issue These metals – rare or otherwise – play a vital role in the switch to electric vehicles and wind turbines.

Figure 1 Charging the battery of a Citroen car

The green revolution means ever more mining of these unfamiliar-sounding metals. What are they? Why are they needed? Where are they found?

To clarify the technical language: “rare earth” is the name given to a set of seventeen metals that are all silvery-white and soft. The name is misleading because they are not actually scarce – it just took a long time to isolate them. They are found in the Earth’s crust and are fairly abundant, though thinly distributed and chemically compounded with other elements in various kinds of ore. As a result, a lot of effort (and expense) is required to extract them from their ores and purify them for use. They are indeed essential for many electrical devices.

Some of these raw materials come from mining and some from recycling. The aim would be to develop a circular economy, in which materials are reused and recycled without need for mining fresh supplies, but that ideal is some way off. Some metals already have reasonable recycling rates, with aluminium and cobalt, for example around 70%. But others are much lower: lithium, for example is only 1%.

The energy switch from burning fossil fuels to renewable sources means the production of enormous numbers of solar panels, wind turbines and wave, tidal and hydroelectric generators. The creation of these new sources will require huge quantities of metals such as aluminium, copper, silver and steel as well as some other less well-known elements such as indium, selenium and neodymium. (see Read More below for details).

Turbines and solar panels can supply buildings continuously, but for mobile machines like ships, aircraft and motor vehicles, the energy has to be piped in and stored. Batteries are essential and these are made from metals.

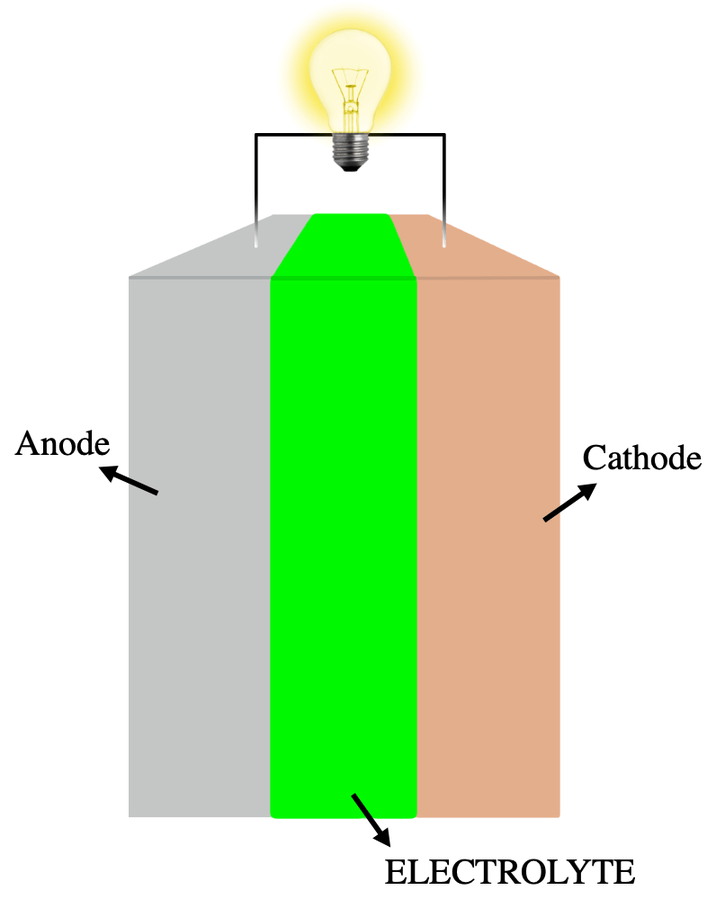

In its basic form, a battery consists of two dissimilar metals, linked to its + and – terminals (called cathode and anode). These are separated by a substance that can carry electrical charges from one metal to the other (called an electrolyte). Strictly speaking, one of these is called a cell; a battery is a collection of these linked together, much as a military battery is a collection of weapons.

Figure 2 A simple battery (strictly, an electrical cell)

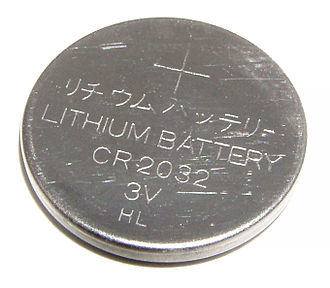

Different kinds of metals are used to make various kinds of battery; lithium and cobalt are common examples.

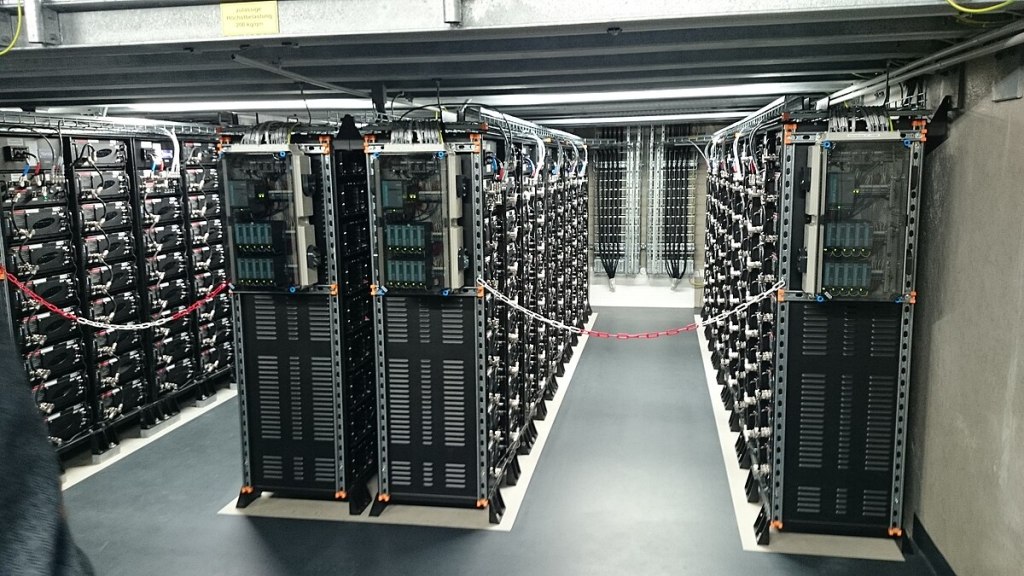

A modern energy storage plant like that shown in figure 3 is built of thousands of such cells linked together.

Figure 3 Battery plant for storing electrical energy

A smaller version of the same makes up the battery pack of an electric vehicle, such as the one shown in figure 4.

Figure 4 Battery pack for a BMW-i3 electric vehicle

Enormous quantities of metals will be needed to power the electric vehicles of the future. In the UK alone, over 200,000 tonnes of cobalt and even more lithium will be needed, as well as smaller amounts of less well-known elements (neodymium and dysprosium). Copper, used for the wiring in almost every device, will be needed in ten times these amounts. For the world as whole, roughly forty times these amounts will be needed. Recycling is expected to mitigate the need for fresh mining, for example through scrappage of used vehicles. This could supply significant amounts of lithium and cobalt (perhaps up to 30–40% in the USA in ten years’ time).

Metals are locked up within minerals, which are themselves combined with other unwanted material in the form of ores. Mining of ores to power the green revolution is already giving rise to new geopolitical tensions. For example, the world’s cobalt supply comes mainly from the Democratic Republic of the Congo where extraction is the cause of humanitarian and environmental concerns. Some cobalt could be recovered from waste material in nickel mines in Europe; this could potentially supply around half of the demand for batteries in Europe.

A further worrying environmental concern is the pressure to mine the nodules that lie on the ocean floor. These are formed from compounds in the water that precipitate out very slowly, over millions of years. They are commercially attractive however, because they contain all the cobalt and manganese and most of the copper and nickel needed for the world’s electric vehicles.

Figure 5 Nodules on the ocean floor

Lithium, essential for batteries, is fortunately not rare. About half of the world’s supply comes from Australia and other sources are found in the UK, Portugal and Germany as well as Chile and Argentina. But it’s not just the geographical location of key metals that creates geopolitical tension, but also the ownership. China currently dominates the global supply, controlling about 80% of the world’s production; though others, including the United States, Australia, and Canada are now investing in the development of their own resources.

What are metals?

But what exactly are metals? What is it that tiny button batteries and giant turbines blades have in common?

A key feature of all metals is that they conduct electricity. This is the result of the way the atoms that make up a metal are joined together. They sit next to each other in a rigid array, like eggs in an eggbox, but in three dimensions. Like all atoms, metal atoms are made of particles, most of which are electrically charged. But touching a metal (or any other atom) on its own doesn’t give you a shock because the negatively charged particles exactly balance the positively charged ones. In other materials the charged particles (called protons and electrons) stick firmly together within each atom. In metals, however, one or more electrons is released from each atom and wanders around freely in the space between atoms.

The zillions of electrons in a piece of metal are just buzzing around in random directions, bumping into the atoms they’ve deserted, changing direction every time. As a result, there is no overall movement of electrons, their movements just cancel each other out.

Figure 6 Animaiton of free electrons and the atoms they have left

When a voltage is put across a piece of metal however – from a battery or the mains – it gives the electrons a push in one direction – towards the positive. Because they are free to move, they do so – that’s an electric current. Wires made of metal, usually copper, allow electrons to flow over distances, bringing electrical energy with them across the countryside and into the sockets of your house. That’s why copper is essential for the green revolution.

Different metals have other important properties too. Their strength makes some metals essential for rigid structure such as buildings and railway lines – iron and steel (iron with a little added carbon) are particularly strong. Strength comes from the strong attraction between the sea of free electrons permeating the entire metal and the positively charged atoms from which they have been released. Aluminium is a little less strong but being less dense is useful for building aircraft. Its atoms are both lighter and more widely spaced out.

Other useful metals are not so strong but are flexible, or malleable, meaning they can be easily bent. Lead has this property, making it suitable for lining chimneys, so that rain runs off.

Figure 7 Lead used for the flashing around a chimney

These properties of various metals – strength, density and malleability – mean that many, such as iron, copper and aluminium, have become well known to us due to their everyday usefulness. But what of the demand for the less well-known metals that we hear about, linked to the move away from fossil fuels? What exactly are they needed for?

Lithium, cobalt and nickel are used in the plates of lithium-based batteries because energy is stored especially densely with these materials. As a result, a given size of battery is able to deliver a greater amount of energy and hence make longer journeys possible. Manganese is also used in electric vehicle batteries, not only because it too increases energy density, but also because it makes them less combustible.

But it’s not just the plates of batteries that require unusual metals, so too do the magnets that are an essential part of every electric motor. The most widely used is neodymium; others have equally unfamiliar and bizarre sounding names, like dysprosium and terbium. The reason these are used is that they are strongly magnetic, producing fields much greater than those of iron – and they’re lighter. Powerful magnets form a vital part of the generators used to generate electrical energy in wind turbines.

Semiconductors

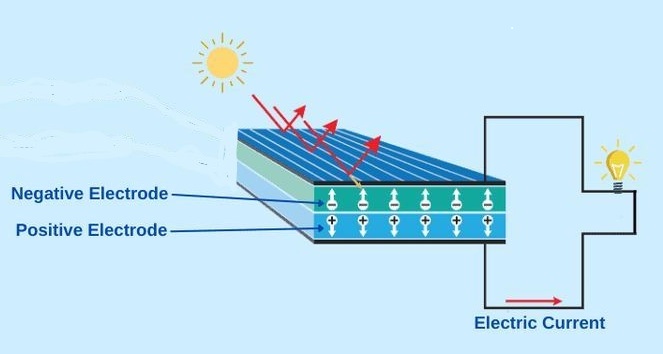

The green revolution involves more than electric vehicles and wind turbines, of course. Solar panels play a major role worldwide and the photovoltaic cells of which they are made use a different kind of material altogether: semiconductors. The latter were only discovered in the 1940s and, as their name implies, they differ from metals in the way they conduct electricity. The atoms in semiconductors do not free up electrons routinely, as they do in metals, but only under specific conditions: in the case of a photovoltaic cell, only when light shines on them. The main semiconducting materials are silicon and germanium, which, ordinarily, do not conduct electricity. However, in photovoltaic cells, the energy in light is sufficient to knock some electrons out of the silicon atoms, freeing them up to move.

When a voltage is applied across them, these free electrons move as an electric current. In effect, energy from the Sun gets transformed into electrical energy.

Figure 8 Operation of a photovoltaic cell

To create the voltage needed to drive this current, atoms of the elements gallium and boron, are inserted as impurities into the silicon and germanium of which semiconductors are made. China controls well over 90% of gallium supply and Turkey is the main producer of boron. Some less familiar metals, the ‘rare earths’ dysprosium and cerium, may also be added in small quantities to improve the efficiency and durability of today’s photovoltaic cells.

Extraction

Metals are not usually found sitting in the earth, bright and shiny as we see them in everyday life. Gold is an exception that proves the rule, thanks to its unusual inability to form chemical bonds with other elements. Indeed, it’s this failure to react with the oxygen in the air that enables it to retain its lustre. Most other metals do combine in this way, forming dull powdery oxides, like the rust that forms on iron or verdigris on copper. The atoms of most metals combine readily with atoms of other elements. Reactions like these have occurred in the rocks of the Earth over the aeons thanks to the intense heat and pressure deep in the mantle (below the crust), a layer in which molten rock flows as magma. Minerals are formed as the magma cools, generally over millions of years.

The rocks we see are generally formed from combinations of different minerals. What we call ‘ore’ is rock or sediment that contains valuable minerals, usually including metals or metal compounds that are economically worth mining

Figure 9 An ore containing copper and arsenic

A mineral may be simply a metallic element, such as gold or copper, but more generally the metal atoms are combined with atoms of other elements such as oxygen, sulphur and silicon. These combinations give rise to names such as oxide, sulphide and silicate.

Retrieving pure metal from the ore is the task of mining companies. This involves blasting and digging ore from the surrounding rock, and then repeatedly crushing, grinding and sieving it.

Figure 10 Lithium mine in Namibia

Separation of the desired ore from the rest and then extracting the metal within it involves a variety of physical actions, using magnetism, floatation or simply gravity. Chemical processes often follow, including dissolving, smelting (heating up to a molten state) or electrolysis (using electric current to purify). As you can imagine many of these processes require energy in some form. So, the green revolution itself has a cost: providing the necessary metals consumes energy and impacts on the environment, both by spoiling land and using large amounts of water.

Conclusion

Clearly, it’s wrong to imagine the transition to greener sources of energy as a simple move from bad and dirty to clean and wholesome! As the above has illustrated, there are trade-offs. Using electricity from renewable sources to power vehicles and drive industry is a huge advance on the historic practice of burning oil and gas; it’s essential to mitigate the effects of climate change. But generating that electrical energy does involve processes that emit carbon dioxide, pollute water reserves and despoil land, to say nothing of the humanitarian consequences for some of those who do the mining. Major geopolitical changes are inevitable as global competition and international trade in metals gradually alters the oil-based economics of the past.

Andrew Morris 4th May 2025

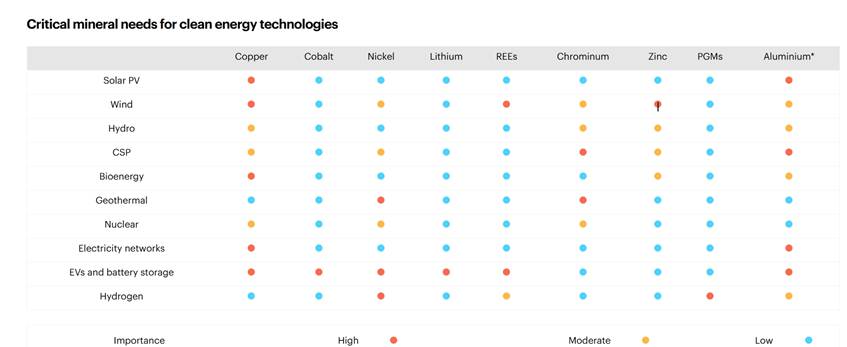

If you are interested in more detail about the various kind of metal involved in a different kinds of renewable energy source, the following table is full of information.

The website from which this table is taken has full information on the minerals needed for the green revolution: Mineral requirements for clean energy transitions – The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions – Analysis – IEA