Jean told her discussion group about a mill she had recently visited for spinning silk, on the river Derwent in Derby. Built on arches over the river, it enabled machines to be driven using the energy in flowing water. It also provided the model for what later became known as a factory. The discussion group were fascinated by the sheer ingenuity of this kind of early industrial engineering and wanted to explore further.

This produced spinning motion at ground floor level, but this needed to be transferred up the floors of the mill to the machinery above. How was this done?

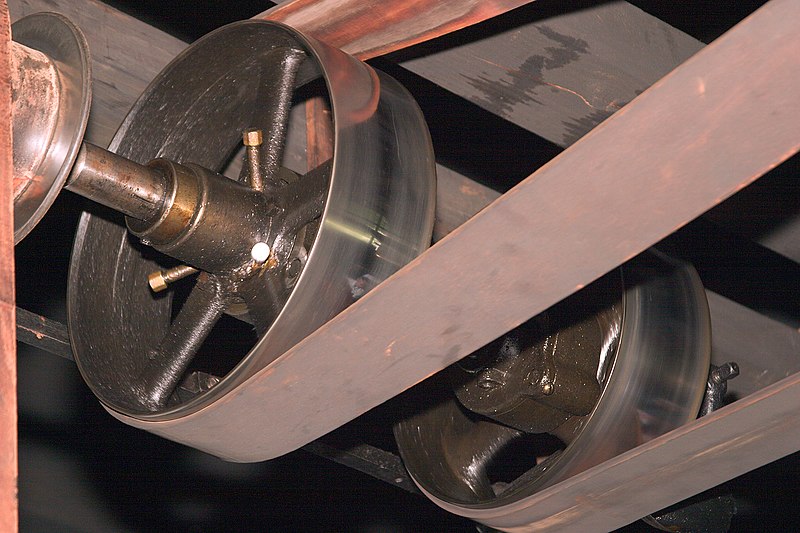

One method, commonly used in the industrial revolution was to attach a leather belt to a pulley wheel on the axle driven by the water wheel (figure 2), and to another pulley on the shaft driving the machinery. Mills built during the industrial revolution used this method extensively.

Figure 2 Flat belt transmission

It’s easy to see in figure 3 how the long rotating shaft gave rise to the repetitive, linear layout of early factories. In this image, large pulley wheels near the ceiling transmit rotation to vertical belts which loop around pulleys on the individual machines

Figure 3 Spinning machines driven by an overhead shaft

The spinning of a wheel can also be transmitted vertically up a building by a quite different method – gears. One beautiful example is the ‘bevel gear’, illustrated in figure 4. Another is the ‘worm gear’ in figure 5.

Figure 4 Bevel gear

Figure 5 Worm gear

Helen saw how beautifully cogs shaped in these ways changed the direction of a rotation. She wondered what the gears that you change through on a car or bike, were for. They are needed because there’s a limit to the amount of force any machine or human body is able to apply to turn a cog.

Looking at figure 6: at the place where the teeth of the two cogs meet, the force of the bigger cog has greater turning effect than the same force on the smaller cog, because it’s further from its axis. It’s like a lever – a spanner with a longer handle, has a greater turning effect.

Figure 6 Gears

But the small cog rotates faster because, with only ten teeth, it has to turn nearly three full circles every time the big cog, with 28 teeth, turns once. So, the big cog has a stronger turning effect, but the small cog spins more rapidly.

Gears in a car or bike or any machine enable choices to be made about which is needed most – a stronger turning effect or greater speed. Clearly when a vehicle has to start from scratch, it needs a strong turning force to get going; similarly, when it is going uphill, where it has to work against gravity. On the other hand, coasting along a flat motorway requires less turning effect and more speed. So, starting off in a ‘low’ gear, the spinning engine is connected to the smaller cog for more power, while the road wheels, which are moving slowly, are connected to the bigger one. Motoring along in ‘high’ gear, the opposite is true.

At this point in the discussion, Helen exclaimed loudly: “engineering is amazing – how do you get from steam in the spout of kettle to the steam engine! I’m in awe of it!” Wendy added to the sense of wonder: “just look at the inside of your boiler at home; it’s mind-boggling.

Steam enters the picture

Of course, a boiler at home, doesn’t actually boil water – it would be pretty dangerous if it did. But it presumably takes its name from the vessels that really did boil water, in order to make steam. As Helen implied, it must have taken a remarkable leap of imagination, looking at the vapour from a kettle, to see its potential to drive machinery.

One of the earliest industrial uses in the UK was to tackle the flooding that plagued deep mines. In Cornwall, where tin was routinely mined, Thomas Newcomen invented a new kind of pump using steam.

A furnace boiled up water, creating steam which was periodically admitted into a cylinder above (figure 7). When the cylinder was full of steam, a valve opened to allow cold water from a tank to be squirted into the steam-filled cylinder. This immediately cooled the steam, which condensed back into water. The absence of steam created a vacuum (strictly, a lower pressure space) which sucked in a piston. The downward motion of this piston pulled down one side of a rocking beam. On the other end, a long rod, reaching down to the bottom of the mine, drew up a quantity of flood water.

Figure 7 Newcomen’s pumping engine

This ingenious way of using heat energy to create steam, and drive a pump, solved a major problem in the mining industry at the time. It was however inefficient, as energy was wasted heating and cooling the cylinder with every stroke. More sophisticated versions by James Watt and Matthew Boulton overcame this problem and secured the place of steam power across many industries. Adapting the machine for such tasks as spinning and weaving, the motion needed to be smooth, and steady, so machines could work continuously.

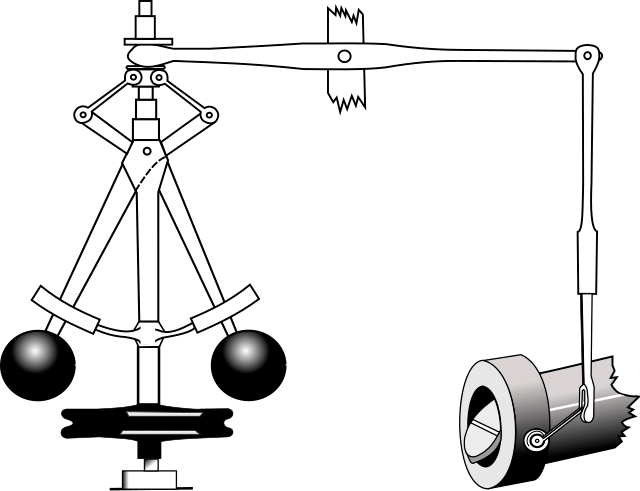

To smooth out the jerkiness of a piston, a flywheel was added, and to regulate speed, the delightfully named ‘centrifugal governor’ was invented (figure 8). If the machine spins too rapidly the balls fly apart centrifugally, causing the attached levers to dampen down the supply of steam.

Figure 8 Centrifugal governor

Steam and water

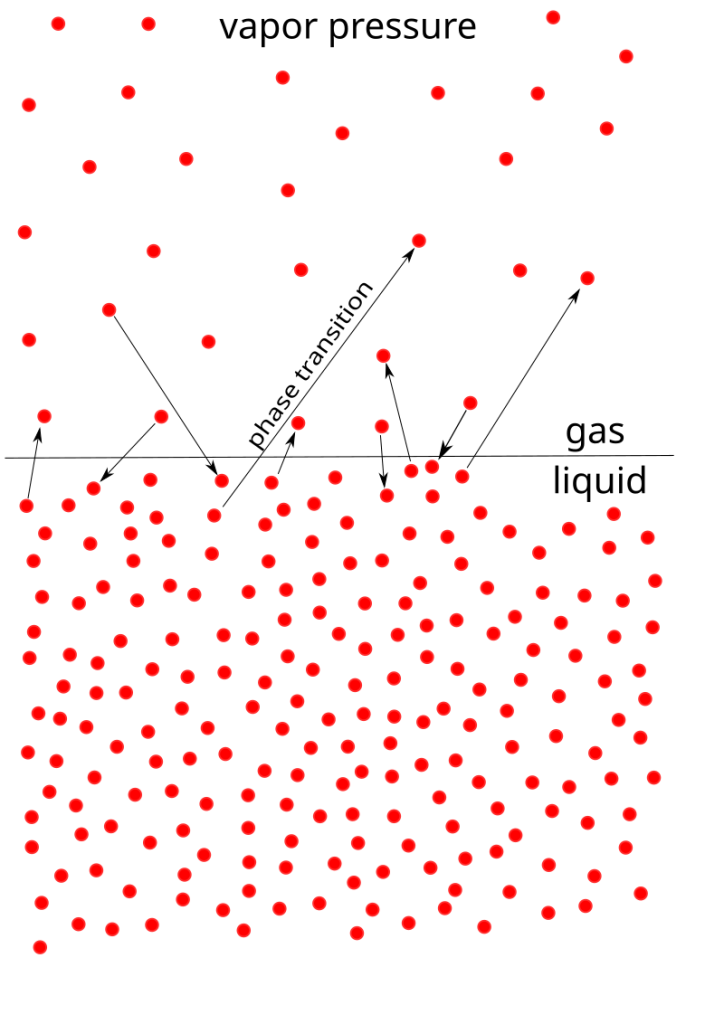

The fact that a partial vacuum can be created by cooling down steam in a chamber is a consequence of a fortunate property of H2O: above 100o Celsius, it is a vapour, and below, it is a liquid.

In the vapour state the molecules of H2O are widely spaced apart and moving fast. When cooled below 100o C, by a squirt of cold water, they slow right down and aggregate into liquid droplets, leaving behind a partial vacuum. Water vapour occupies 1,700 time more space than the same amount of liquid water.

The steam we are able to see, from a kettle for example, is a mixture of water vapour (which is invisible) and tiny droplets of liquid water.

Figure 9 Diagram of H2O molecules in liquid and vapour (labelled gas) states

Locomotives

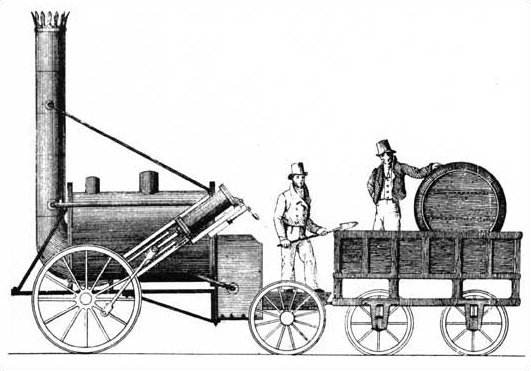

A great step forward was taken when it was realised that the power of steam could be adapted, not just for pumping up and down or spinning static machines, but for turning wheels on the ground … moving a vehicle, in other words. By placing the boiler, cylinder and piston on a frame above a set of wheels, the steam locomotive was born.

Fired up by burning coal in a firebox, steam is created in boiler tubes that run along the length of the locomotive (figure 10).

Figure 10 tubes inside the boiler of a locomotive

Figure 11 shows the beautiful mechanism, known as the ‘Walschaerts valve gear’ invented in Belgium in1844 and adopted widely for locomotives across the world. It transforms the back-and-forth motion of a piston into the rotary motion of the wheels.

Figure 11 Steam driving a locomotive

The high pressure steam (coloured pink, in figure 11) passes from the boiler into the upper cylinder (on the right). This is cunningly designed to admit steam alternately into the left and right chamber of the lower cylinder, so it pushes the main piston on both the forward and backward strokes. The big, long rods connecting the piston to the wheels, are attached to the wheel off-centre (eccentrically) by short ‘cranks’ (numbered 2), enabling the force of the rods to spin the wheels. The rest of the apparatus enables the wheels to be controlled and reversed by the driver through the long rod numbered 8.

In contrast to the Newcomen engine for pumping out mines, the steam is not condensed back into water by cooling it, in this case. Instead, the steam is generated at high pressure in the boiler and this pressure is then applied to the pistons, forcing them to move. Steam is expelled from the cylinders with every stroke of the piston, causing the familiar ‘chuff-chuff’ sound of a steam train.

As figure 11 shows, the original steam locomotive, invented by Robert Stephenson, linked the steam-driven piston to the wheels in a much simpler way!

Figure11 Stephenson’s “Rocket” – an early steam locomotive (1829)

Torque

At this point, the discussion that inspired this blog took an unexpected turn. Helen piped up and asked unexpectedly about the meaning of the word ‘torque’. Her driving instructor had once used the unfamiliar word; it had fascinated and puzzled her. She knew it must be relevant to spinning things. Though not a commonly used word, it denotes a rather straightforward concept. We usually think of forces as making things move along a line – like lifting a box up or pushing a vacuum cleaner forward. But if a force is applied to something off-centre it will also turn it round or make it spin. If we pull on the edge of a frisbee or a playground roundabout or the surface of a cricket ball, it will spin, as well as move forward.

But the amount of spin doesn’t depend just on the force you apply, it also depends on how far away it is from the axis of the rotation. You realise this when you use scissors or a spanner, for example. You get a stronger turning effect from a force the further away it is from the turning point or axis. That’s how we move bolts (on a car wheel for example) that seem stuck …. We use a longer spanner.

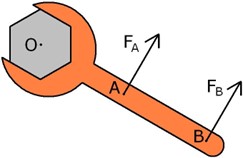

Figure 12 The meaning of ‘torque’

Torque’ captures this fact. It takes into account both the amount of force and how far it is from the axis or pivot. It is simply the amount of force multiplied by this distance. So, in figure 12, the torque produced by a force F is bigger at position B than at A, because it is further from the axis at O

Torque is an essential concept for things that rotate, like engines. It’s also essential in astronomy, as all things in the universe are spinning – planets, moons stars, gas clouds. It’s also important in manoeuvring rockets and satellites; little thrusters, placed off centre, are used to make them turn – i.e. to apply a little torque to the space vehicle.

Conclusion

There are countless examples of ingenious design in engineering. Here we have alighted, somewhat randomly, on just a few of the mechanical inventions of the early industrial revolution. As Jean found in the museum she visited, they are awe-inspiring, once you find out about them. They stand as testament to the imagination and creativity of their inventors, as much as to their practical skill and theoretical knowledge. Other branches of engineering play a major role in our lives today – electrical, electronic, civil, automotive to name but a few. So much of the achievement in these fields is invisible, and goes unreported; it’s always worth popping into a museum or taking a closer look at the machinery, buildings and devices that we routinely use.

© Andrew Morris 29thSeptember 2024