Electricity is getting political – about time too! Until now, it’s just been there for us, at the ready, in sockets and batteries. We’ve taken it so much for granted that we barely give a second thought to where it came from or how it got to us. Power generation and distribution have hardly been bar-room topics. Now they are.

How will the National Grid cope? Will new pylons bestride our cherished countryside? Where will the metals come from for all those new batteries?

Discussion in one science group focussed on this issue. An episode of the TV series Downton Abbey had recreated the moment electricity was introduced into that grand house in 1912 – it’s that recent. The UK National Grid was established soon after, in a moment of public-spirited foresight in 1933. Wendy recalled the introduction of electrical goods into her childhood home in the 1960s. She realised for young people today it would be impossible to imagine life without them. Sarah wondered how the energy for electric vehicles was going to be delivered everywhere it’ll be needed.

Discussion turned to the big question of climate change. Will we each have to use less energy? Where will renewable energy come from when the wind isn’t blowing, and the sun isn’t shining? Will extracting rare metals for batteries bring new global exploitation? Can electrical energy be stored? In the face of these global challenges for society, it soon became clear how little everyone understood about the basics: what electricity actually is, how its generated and distributed. This blog can’t answer the big political questions about the future; but it can at least set out some of the underlying scientific concepts that will help us understand what lies ahead.

What is electricity?

It’s a remarkable, simple fact that all matter is electrical. We don’t notice it ordinarily because it occurs in two opposite forms that are exactly balanced, most of the time – we call them positive and negative charge. Matter is made of atoms, and these are made of positive and negative particles in exactly equal numbers. Electrical effects were first noted in ancient times when amber was rubbed with a cloth. It’s the same today with plastics, when we run a comb through our hair or take off an acrylic jumper, for example.

These actions physically move some of the negatively charged particles from their atoms, transferring them from one object to the other. One becomes slightly positive and the other slightly negative, so they interact. This kind of electricity stays stuck on things like combs and jumpers. That’s why it’s called static.

Figuure 1 static electricity

To be useful, charged particles need to move, carrying energy with them. That’s what a current is – by analogy with a flowing river. To move, it needs both a source of energy to drive it and a suitable material to flow through. Metals and a few other materials (called conductors) allow flow, others resist it (called insulators). A voltage provides the drive to make charges flow. Known technically as ‘potential difference’, it’s rather like the height difference that causes rivers to run downhill and tap water to flow from roof tanks.

If you’d like to find out what is meant by the words Volts, Amps and Watts, click on this extra explainer.

Power stations, wind turbines and batteries are sources of voltage, giving energy to each charged particle that flows in the current. The greater the voltage, the greater energy. But where does the source – the turbine or battery – get its energy from? And how is it turned into electrical form?

The giant sails of a wind turbine give us a visual clue – the force of the wind causes machinery inside the housing to spin. Tightly wound wires on the spinning rotor cut through a magnetic field. This creates a voltage across the ends of the wire, as it does whenever any kind of metal passes by a magnet. It’s the basis of electrical generation in all kinds of power stations – hydro, wind, coal, oil or nuclear.

Figure 2 wind turbine

Turbines are designed to spin the wires of the rotating part, traditionally using steam from furnaces or nuclear reactors to drive them. It’s the burning process or nuclear reactions that releases the energy pent up in the fuel. In some upland areas of Scotland and Wales, and in mountainous places elsewhere, the same spinning effect can be produced without fuel, from energy carried by water gushing down from a height.

Whichever source of energy is driving the turbines, the obvious science question is: how does the act of spinning lead to electrical energy? In other words, what’s does a turbine do?

Generating electricity

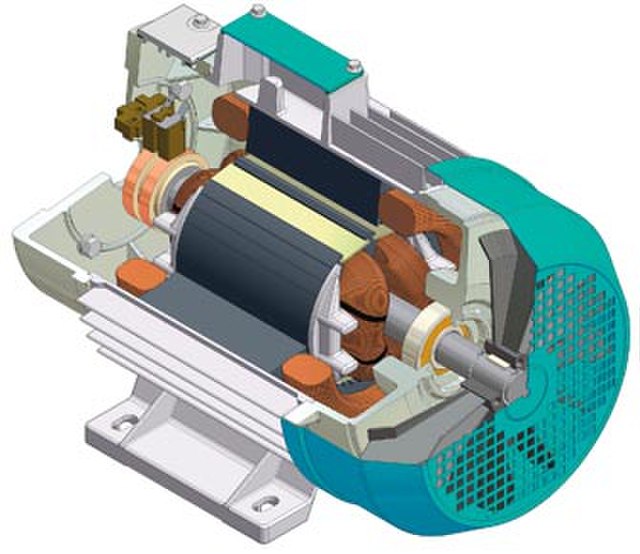

Attached to the spinning turbine is a large rotating frame strung with copper wires, in large coils (just one coil is shown in figure 3). Called a rotor, this spins the wires rapidly. Around the wires, a set of magnets is carefully arranged – usually electromagnets, rather than the bar magnets you see at school. This enables the wires of the rotor to cut through the zone of influence of the magnets (called the magnetic ‘field’).

Figure 3 generating electricity

It had been discovered back in 1831 that when this happens, electric charges in the wires acquire energy and are driven to move, if they are free to do so. The amount of energy that each charge acquires is what we mean by voltage. Thus, a 3 Volt battery delivers a lot less energy with each unit of electric charge that flows, than the 240 volts of the mains supply (80 time less).

When the rotor of a generator is connected to external wires – such as the power cables that run across the country, all the wires, both inside and outside the turbine, acquire energy and start to move. When your kettle is switched on, the wires inside it become energised directly from the spinning of the rotors in power stations and wind turbines.

Figure 4 inside a generator

It takes almost no time for electrical energy to move – what you are using at any time is being generated at that exact moment.

Figure 5 Turbine hall in a power station

Distribution

It’s hard to imagine that the electrical energy you use as you boil a kettle is being generated at that exact instant. Unlike piles of coal or barrels of oil, electrical energy can only be stored in small amounts in batteries or capacitors. Even the tiny amount of electrical energy stored in an acrylic jumper as you take it off, is at such a high voltage that it creates a spark – a breakdown of the air – dissipating the energy. So, the crucial issue is not how to store electrical energy but how to distribute it in such a way the energy being generated at any instant connects directly to the points where it is being used that instant – the sockets in your kitchen, the machines in factories, the charging point on the streets.

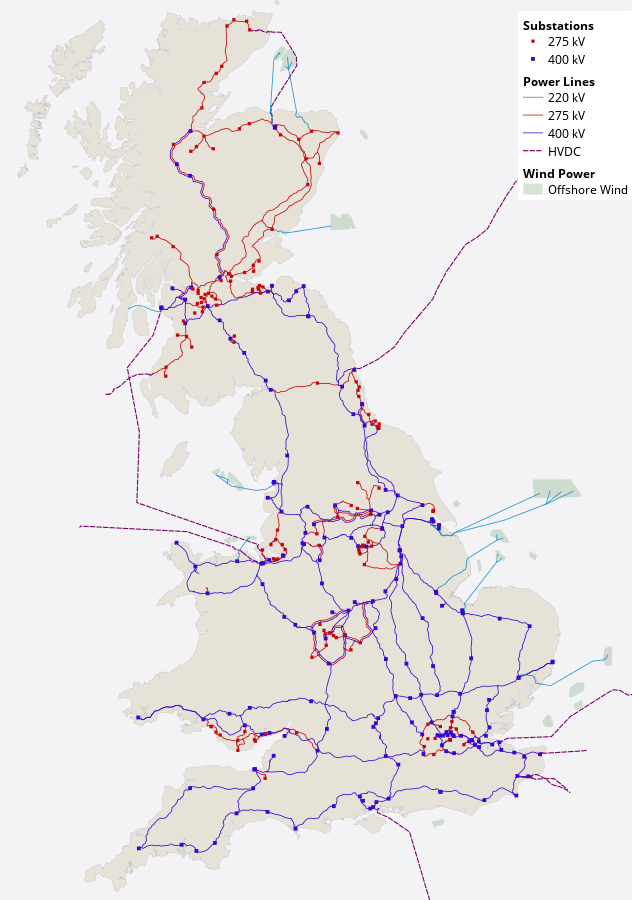

To achieve equality between the energy being generated and consumed, all the power stations, wind turbines and other sources of supply are linked together in one great network – in the UK, the National Grid. This way, as demand rises (e.g. at breakfast time), more power sources can be started up to supply energy through the grid; and when demand subsides, some can be switched off. The lines in the map show where cables run across the country, often supported on giant pylons. As the colours in the key indicate, different cables operate at different voltages – from 220 to 400 kilovolts (kV, or thousands of volts). That’s a huge amount of energy to be carried with each charged particle – much too much for safety at home.

Figure 6 Map of the UK National Grid

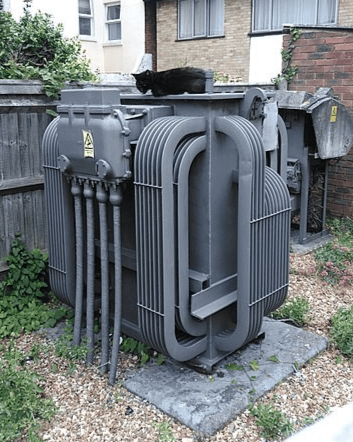

Whenever electricity is transmitted through cables a fraction of the energy is always lost, as the electrons battle with the resistance of the wires. But this loss is proportionately less when the voltage is higher. That’s why power cables operate at such high voltages even though it’s generated at the power station at only 11,000 volts (11kV) (in the UK). The voltage has to be raised for transmission (to hundreds of kilovolts instead of 11kV, as the diagram in figure 6 shows). That is what transformers do – raise or lower voltages.

To deliver the energy to factories and homes, transformers in local areas step down the voltage so it is safer to use domestically (230 volts in our homes, 415 volts in industrial buildings).

Figure 7 A transformer

That’s why substations and transformers are dotted around our towns and countryside – to drop the voltage down, in our neighbourhood. (figure xxx)

Figure 8 A substation

Adding more to the grid

It’s widely understood today that we need to reduce oil and gas burning to cut carbon dioxide emissions. Fossil fuel energy is being replaced by electrical energy to power trains, cars, heat pumps, steel production and countless other industrial processes. As the world begins to combat climate change, electrical energy is being generated and consumed in different places. Sources of energy are moving away from inland power stations close to coalfields, to windfarms in the sea and nuclear power stations on the coast. Energy consumption will also be moving as charging points for electric vehicles begin to appear in neighbourhood streets and motorway service stations spread across the country. New patterns of flow will require pylons to carry the cables along new routes (burying cables underground costs a lot more). New lines will be needed to connect up these new centres of supply and demand. The actual amount of energy that will be required in future is slightly less of a problem for the National Grid as this has fortunately been reducing in recent years, thanks to improved energy efficiency. The extra demands of electric vehicles is not expected to stretch the grid further than it has already been at its peak in the recent past.

Energy from water

Energy is also inherent in the way water moves. It may lie high up in mountain lakes and streams, where, due to its height, it has gravitational energy. This can be tapped into by channelling the water to a lower level through the blades of a turbine, much like the old watermills.

Gravitational energy also drives the tides, as the Moon and Earth pull on each other. This causes the seas to rise up towards the Moon and away from the shore, in a daily rhythm as the Earth rotates.

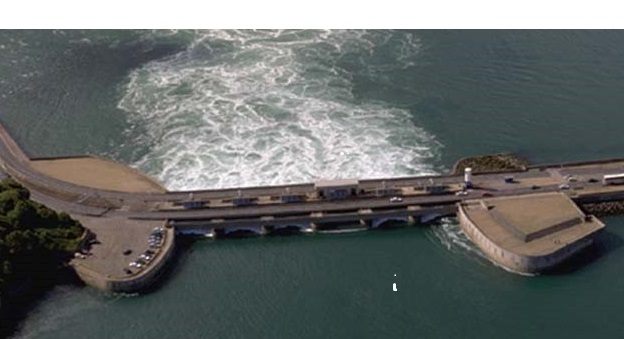

The incoming and outgoing water can be captured in the blades of turbines, generating energy as they spin. The example shown in figure 9 is on the north coast of France.

Figure 9 A tidal power station.

It’s also gravitational energy, held in the height of a wave that can be harnessed as a wave loses height when it collapses.

Figure 10 The principle of wave energy

The presence of ample water around the shores of the British Isles and in its rain-fed lakes, locks, loughs and llyns, is particularly fortunate for renewable energy generation in the UK. The location of these sources, however, far from traditional power stations, will again require changes to the shape of the distribution network.

Solar panels

Solar panels (aka photovoltaic panels) are now commonplace on rooves and in great ‘farms’ replacing crops in some places. As they clearly involve no rotating parts, how do they generate electrical energy? Of course, the electrical energy they produce is just the same as from any other source; but the way they do it is entirely different from the electromagnetism of generators spinning in turbines.

As we’ve already seen, electricity is the flow of charged particles, and all atoms are made of charged particles. In most materials, these charged particles are all firmly bound into atoms and can’t be made to move in normal conditions (these are the insulators, like rubber or stone or glass). In conducting materials, like metal, some of the negatively charged particles – electrons – are freed up from their atoms and can be made to move as soon as a voltage is applied across a piece of metal.

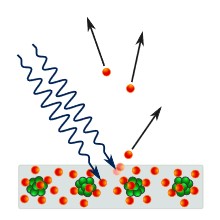

In the last century, a different class of materials was discovered, of which silicon is the most well-known, with intermediate properties between insulators and conductors. Not surprisingly, they were dubbed ‘semi-conductors’. Solar panels (aka photovoltaics) contain silicon. In the dark they do nothing, but when light falls on silicon atoms, energy in the light knocks some electrons out of their place in the atoms, freeing them up to move. These electrons are thus energised and are ready to flow if and when they are connected to a circuit, carrying their energy with them.

Figure 11 Semiconduction in solar panels

Batteries

Batteries are quite different. They are able to deliver a current, not because of an electromagnetic effect, but because of the chemicals they are made from. The external result, however, is the same – negatively charged particles (electrons) are produced that can flow through wires in a torch, cell phone or other device. The release of electrons that can then flow through a wire is the result of two complementary chemical reactions occurring at the two ends of the battery. To read in greater detail how this happens, see Read More , below.

Conclusion

It’s clear the world is going to have to switch to renewable sources to supply its energy in future years. In most cases this will result in more energy being used in its electrical form, rather than the chemical form of petrol, oil and gas. Changes will occur both in the way electrical energy is generated (from wind, water and sun), and in the places it’s consumed (on the roads, in the air and at sea). Innovation will alter industrial processes that involve burning fossil fuels – such as steelmaking and cement manufacture. As these changes occur in our lives, it will be helpful having a basic understanding of what electrical energy is, how it’s generated and what makes it flows.

© Andrew Morris 18th July 2024

Read More

Batteries

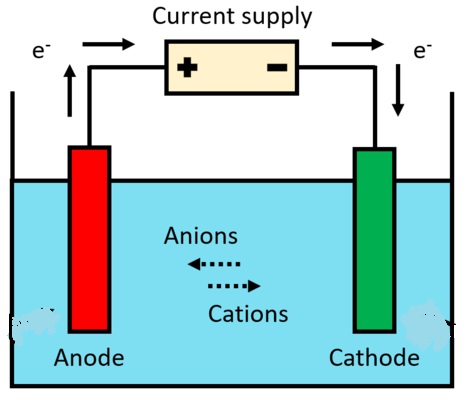

A battery has two terminals made of different materials and separated by a paste or liquid. At one end, marked with a – sign, the metal of the terminal reacts with a chemical in the paste or liquid with which it is in contact. The result of this is to release electrons from the atoms of the terminal. These sit there, waiting to be used. At the other end, electrons are taken away from the atoms of the + terminal and absorbed into the paste or liquid.

Figure 12 Principle of a battery

If the metals of the two terminals were the same, nothing would happen. because the release of electrons at one end would be cancelled out by absorption at the other end. Different metals have different pulling power for electrons, however. So, with dissimilar metals at each terminal, one pulls more than the other. When a wire or piece of metal is connected between the – and + terminals, a current will flow from the battery. This may light up a torch bulb, power a cell phone or even an e-bike or e-vehicle. The energy carried by each electron originates from the breakdown of chemicals within the battery.

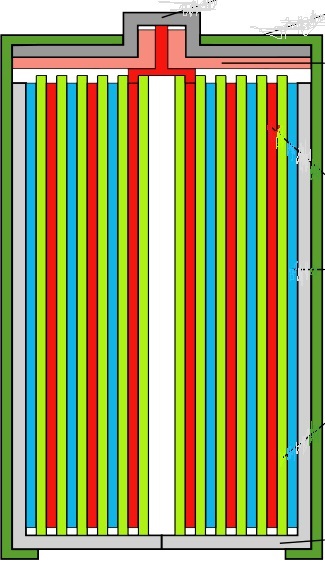

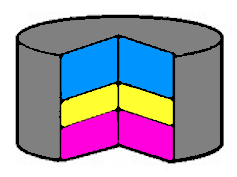

In practical batteries, the three main elements – i.e the +ve and –ve parts plus the separating material between – can be arranged in various ways. Figure 13 shows a typical torch battery in which the +ve and -ve parts are interleaved sheets, with a paste in between. These are rolled up into a cylinder, like a Swiss roll.

In this cross section of a Swiss roll battery, the blue lines are slices-through the layers of the negative material which all connect to the negative terminal, the plate at the bottom indicated in grey, This is where electrons leave the battery into your device.

The redlines are a cut-through the layers of positive material which connect to the terminal on the top of the battery. This is where electrons enter the battery from the external circuit.

Green indicates the paste or liquid layer in between.

Figure 13 Cross section of a Swiss roll type battery

In the simpler design of a ‘button’ battery (Figure 14), electrons leave from the negative layer, coloured pink and enter from the external circuit via the blue layer. The yellow layer is a moist separator. These are commonly used in watches, weighing scales and other devices.

Figure 14 Cross sectoin of a button type battery

The chemical reactions occur where the positive and negative parts of a battery meet the material that separates them. Over time, these reactions gradually degrade these materials. Batteries become depleted, no longer able to release electrons. Rechargeable batteries, on the other had work by reversing the chemical reactions that have occurred. A slightly stronger voltage is placed across the terminals of the battery, by a charger of the right voltage. This pushes electrons back in the opposite direction through the battery, reversing the chemical reactions and restoring the terminals to their original state, ready for further use.

Rapidly rising use of batteries, especially for electric vehicles, will mean demand for the metals of which they are made will increase dramatically. Mining for these is already on the increase and recycling is likely to become a regular feature of battery technology.