Chemistry at school – not a pleasant memory! I used to enjoy most subjects – woodwork, geography, English, maths – but chemistry never appealed. It seemed so remote from anything real in life: Bunsen burners, titration, litmus paper – a litany of strange, irrelevant words. It got worse each year: the law of multiple proportions, Avagadro’s number, the inexplicable mole!

I pulled out as soon as I had the choice. Little did I appreciate, at that tender age what a magnificent and intensely relevant subject it actually is. It was years later, after a period of self-study that I discovered what it really had to offer; how intimately it connects with our lives, how fascinating are its discoveries. The aim of this blog is to make good on my mistaken rejection of the subject at school, and to try to encourage others who did the same to look again at its virtues. It describes how central chemistry is to our everyday lives and looks at some of the basic concepts that seemed so dry and baffling back in my schooldays.

Chemistry in everyday life

The ‘chemists’ shop or pharmacy is perhaps the most obvious connection each of us has with the subject. One of the most common businesses on the high street, it offers a huge range of substances to enhance our health (or beauty). The workings of our body act as a first connection with chemistry. The idea that specific substances can interact with specifc organs is ancient; it long predates any understanding of how such processes actually work. Indeed, it was through experiences and beliefs handed down as ‘folk wisdom’ that extracts from the willow tree or foxglove, for example, were found to be effective remedies (aspirin for pain and digitalis for the heart, respectively).

Apothecaries experimented, noting how people responded to their various potions. Sometimes they hit on a genuine medicinal property; at other times it was the body’s inherent tendency to heal that did the trick. Meanwhile, natural philosophers (as scientists were once known) were trying to work out what substances are actually made of. The more theoretical ones adopted the ancient Greek theory that the materials we see are composed of tiny, invisible fundamental particles, named ‘atoms’. The more practical ones were testing what happens when one natural substance was brought into contact with another; acid from a lemon dripped onto a piece of copper, for example. These two approaches – theoretical and experimental – have gone hand-in-hand ever since, giving us the picture we have today of what substances are and how they interact with one another.

Living things

We now understand that trees, plants, ourselves and other living things are all composed of tiny, invisible particles called molecules, which interact with one another in chemical reactions. Each molecule is itself built out of the more fundamental particles that make them up – atoms. A chemical reaction is a process in which two different kinds of molecule come very close to each other, enabling the atoms of the two to rearrange themselves, forming new and different molecules (see the Read More section, below) .

The branch of chemistry that deals with the main molecules in plants, trees, animals and other living things is called organic chemistry. Living material here on Earth is made almost entirely of molecules based on one kind of atom – the element carbon. Most organic substances, such as carbohydrates, fats and proteins also contain atoms of the elements hydrogen and oxygen as well, attached to the carbon ones (plus some others in trace amounts). This universal role of carbon atoms is fundamental to the processes of life and is a consequence of the unique flexibility in the ways carbon atoms can attach themselves to other atoms. They have the capacity to bond to either one, two, three or four other atoms – a very unusual trick. So, organic chemistry is a branch of the subject that deals almost entirely with carbon-based compounds.

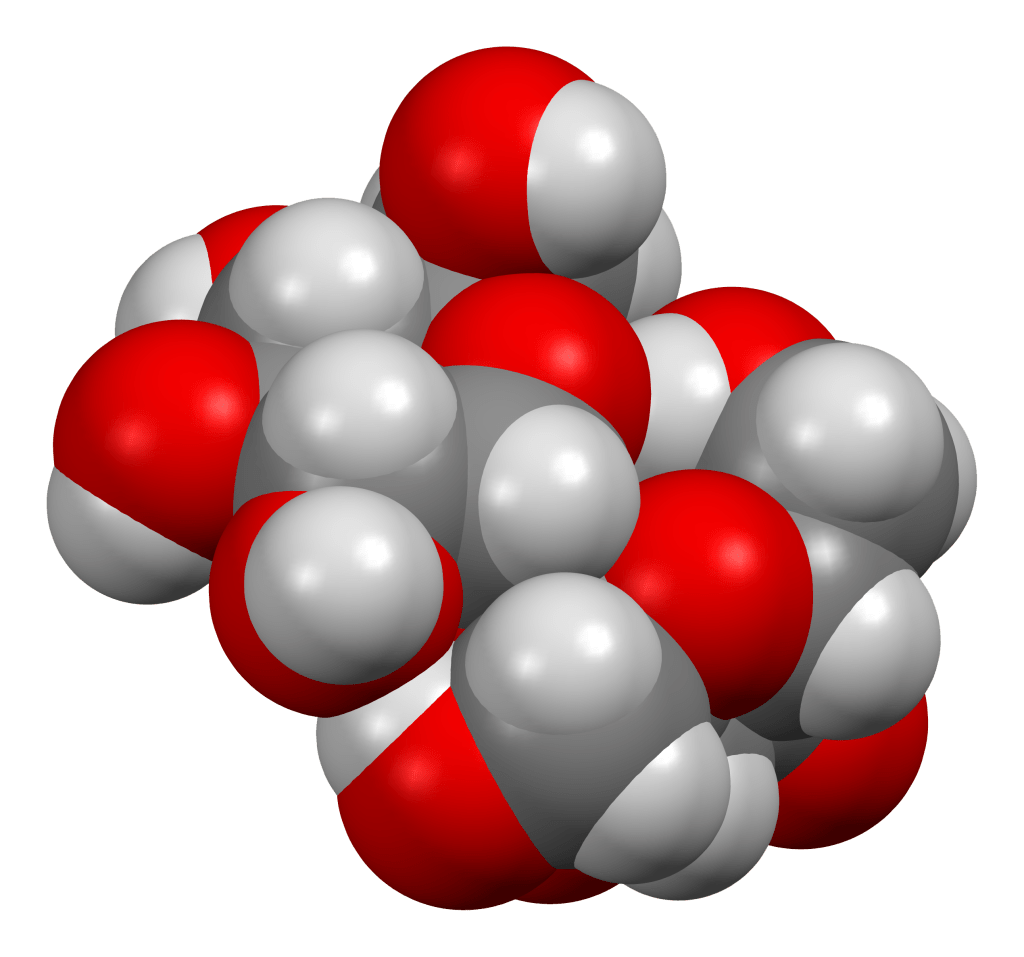

Here are models of some well-known molecules. Carbon atoms are black or grey, oxygen red and hydrogen white. Not to scale – there are thousands of atoms in a molecule of actin.

Biological chemistry

Returning to our theme of medicines, we now understand that almost all the components of our bodies and other living material are organic molecules of one kind or another. Enzymes, hormones, genes and all the components that make up the cells of living tissue are made of molecules. There are many classes of molecule in our bodies and other living tissue, including proteins, carbohydrates, nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), fats and sugars. They vary dramatically in size, from the small molecules of water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2), with just three atoms each, to giant proteins and assemblies of many proteins comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms.

Molecules within our bodies are interacting all the time at incredible speed –neurotransmitters, such as adrenaline and serotonin, carry signals between nerve cells; enzymes break up protein and carbohydrate molecules to release energy, and antibodies latch on to unwanted bacteria and viruses to eliminate them. Molecules that enter into our bodies also interact in vital ways with others inside us: molecules in the food we eat, for example, and in medicines and the substances we inhale from the air. These molecules and the interactions they have with one another are the subject matter of biochemistry. This branch of chemistry is central to our understanding of medicine, pharmacology, agriculture, food science, nutrition, sports science and many other fields featuring living systems.

Fuels

Organic molecules also play a huge part in our lives, quite apart from their role in our bodies. We all know that we eat in order to gain energy – it’s essential for life. Food is, in effect a fuel that we burn. The molecules we eat – proteins, starch, fats and sugars – carry energy with them. This energy gets released when molecules from the food get broken down into smaller, simpler ones. This process is happening all the time, in almost every cell of our bodies. It is a kind of combustion process, in which the oxygen we breathe in reacts with the broken-down food molecules, releasing energy. The simple end products of this combustion process are well known to us all: carbon dioxide we breathe out and water we dispose of in urine.

Energy is not only locked up in the molecules of food, it’s also held in the chemicals we know as fossil fuels: oil, gas and coal, mainly. These also burn in the presence of oxygen, releasing energy, and producing carbon dioxide and water as waste products. It’s this energy appearing in the form of heat that warms our homes, drives our electrical generators and internal combustion engines. A major branch of chemistry deals with the refinement of oils and purification of gases, as well as efficient ways of extracting the energy from fuels.

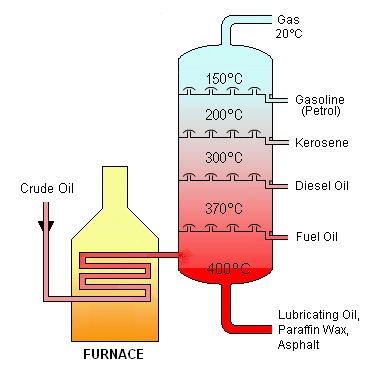

Crude oil, extracted from the ground, is a mixture of larger and smaller organic molecules. They need to be separated to be useful as different kinds of fuel. To do this, crude oil is heated to a vapour then passed into a distilling column. Here, the largest molecules turn back from the vapour to liquid form and drain out nearer the bottom of the column where it’s hottest. The lighter ones remain in vapour form till they get higher up, where its cooler and they liquify (figure 5).

Figure 5 Oil distillation

Natural gas is also a mixture of different kinds of organic molecule. The main one, methane, is pumped to our homes for burning, after purification to remove other gases such as butane and propane. The flames in our boilers and gas hobs are the result of a chemical reaction between molecules of methane in the gas and oxygen in the air. A spark or pilot flame is needed initially, to raise the temperature of the gases sufficiently to start the reaction; the heat produced by the reaction then keeps it going as a continuous flame, so long as the methane flows.

Industrial chemistry

Oil and gas are just two examples of the much wider field of industrial chemistry. This branch of chemistry is, of course, very ancient. Long before modern science began conducting experiments and taking measurements, early civilisations were smelting ores to produce metals and melting substances such as silica, potash and lime to produce glass.

Chemistry was also involved in early textile production when cloth was bleached and dyed. Wood ash was used for this purpose by the ancient Egyptians, and later medieval cultures used acid from sour milk.

Figure 6 cloth dyeing in India

But it was in the nineteenth century that industrialisation of chemistry really took off. In 1856, an eighteen-year-old London student, William Perkin, stumbled on a way of making the first artificial purple dye from a useless by-product of coalmining, coal tar. The massive stocks of this waste product lining the coalfields of the Rhineland inspired German and Swiss industrialists to expand their dye industries, starting up chemical businesses, such as BASF, Bayer and Hoechst, that remain world leaders today.

Dyes may have kicked off the massive expansion of the chemical industry in the nineteenth century, but plenty of other manufacturing processes of importance to our everyday lives also blossomed.

Soaps and detergents date back to ancient Babylonia, when wood ash and oil were combined to wash woollen clothing. In 1807, Andrew Pears began manufacturing the soap that still bears his name in London by reacting the fat in beef suet, known as tallow, with an alkali, such as caustic soda or potash.

Figure 7 soap production in Nablus

Discoveries in the twentieth century led onto to a completely new field of chemistry, that we now call ‘plastics’ (a memorable phrase for anyone who saw the film ‘The Graduate’). The word plastic refers to the mouldable property of the material.

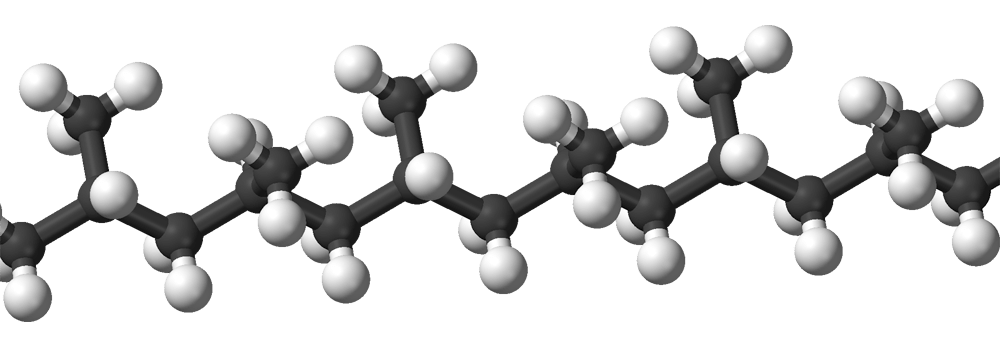

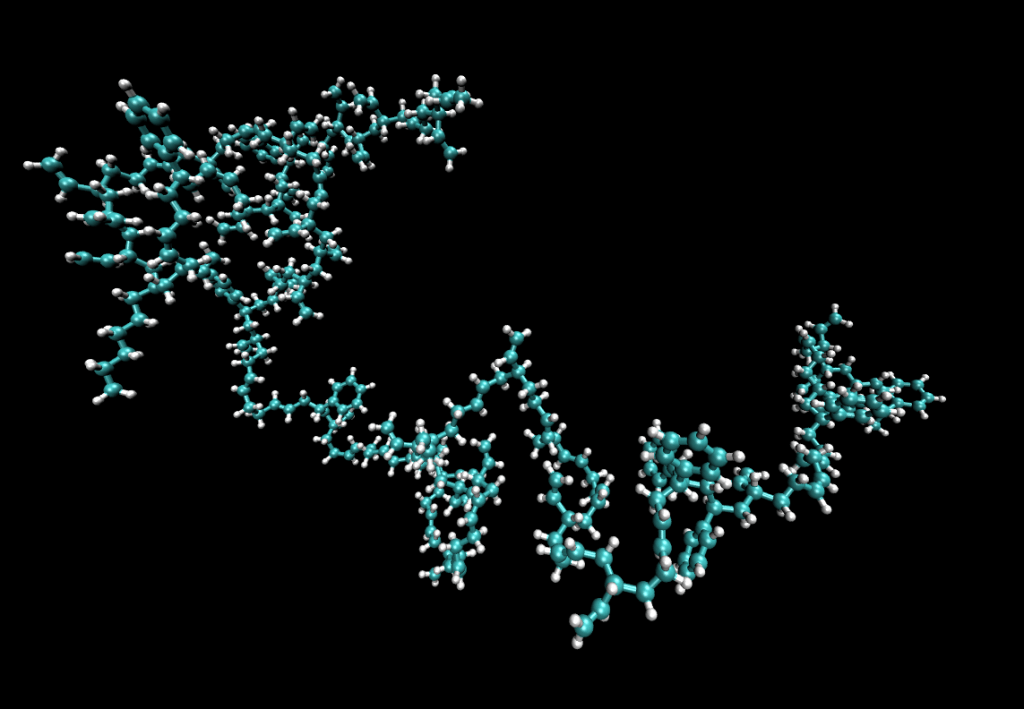

Plastic materials are made of long, chain-like molecules called polymers. The links of these chains are carbon atoms to which hydrogen atoms are attached in various ways.

Figure 8 Model of a polymer molecule in synthetic rubber

Polymers such as polypropylene, nylon and acrylic are produced synthetically, but polymers also occur naturally, a notable example being the cellulose found in the walls of plants.

The first plastic was created in the mid-nineteenth century in Birmingham by treating naturally occurring cellulose from plants with an acid. Soon after, countless new kinds of polymer were invented, leading to today’s global industry, providing soft and hard materials, from polythene bags to artificial heart valves.

Food and agriculture

It’s a great pity that the world ‘chemical’ has acquired such a negative connotation. For many, it denotes an artificially produced substance, inferior to naturally occurring ones and potentially damaging to health. In reality, the word applies equally to substances whether naturally occurring or not; there is no difference. Artificial ones could potentially be damaging to health, of course, as many naturally occurring ones are (think death cap mushrooms and hemlock). Newly invented substances need to be thoroughly tested to check they are safe – another important aspect of industrial chemistry.

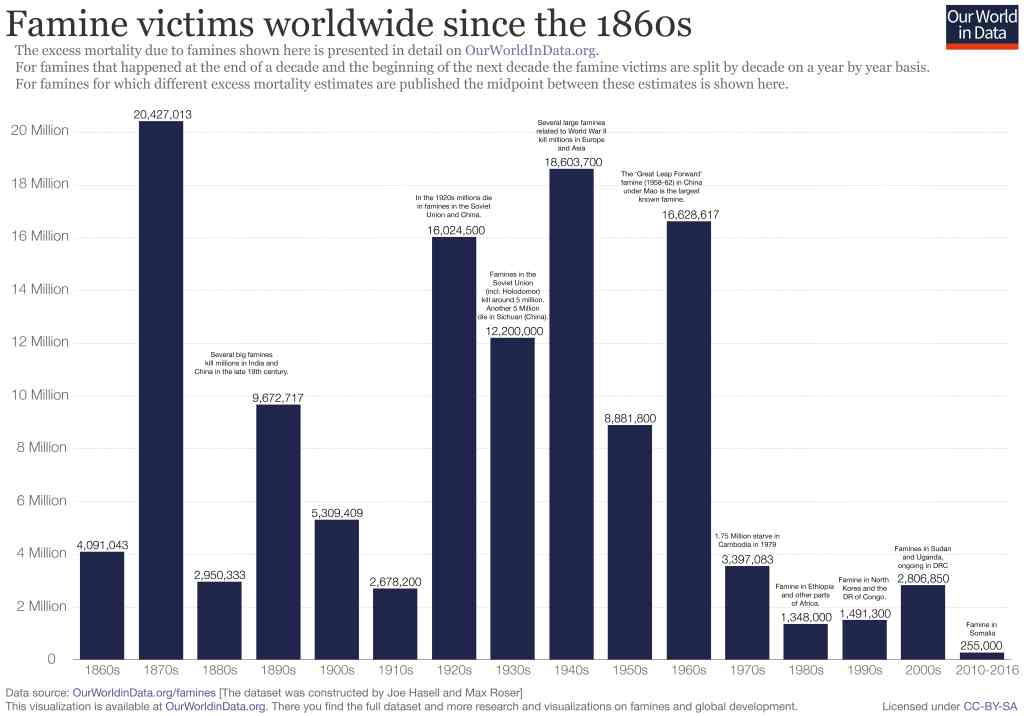

Food production has long made good use of chemistry. Manure, an ancient fertiliser, is rich in proteins, carbohydrates, fats and essential elements such as nitrogen, potassium and sodium – all needed by newly growing plants. The most important chemical of all, water, has always been understood as essential in food production; it was central to the development of early civilisations around the rivers of Mesopotamia and Egypt. The composition of soil and plant material are important areas for chemistry research today. New substances and techniques are helping improve crop yields, protect against pests and diseases, and preserve foodstuffs – crucial aspects of feeding the world’s population. Improvements in the quality of fertilisers, pesticides and animal feed have contributed significantly to the massive reduction in worldwide famine levels since the 1960s.

Figure 13 Chart showing recent reduction in worldwide famine levels

It’s a great pity the industry also plays a role in inserting dangerously high levels of sugars and fats into so many manufactured food products. The link between excessive quantities of these ingredients and diabetes and heart disease has been established definitively by scientists working across chemistry and biological sciences.

Cattle rearing is also being shown, by chemical analyses, to be a significant contributor to the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Methane gas, a by-product of the digestion processes of ruminant animals, is considerably more damaging than carbon dioxide.

Figure 14 Methane production in cows

Pharmaceuticals

The chemist’s shop or pharmacy is your local representative of the vast, global pharmaceutical industry. Its medicinal products are usually a mixture of different chemicals: an ‘active ingredient’ plus one or two adjuncts included to help preserve it and deliver it within the body. The pharmaceutical industry employs medicinal chemists to seek out potential remedies, then to test them for efficacy, toxicity and durability. This is an arduous and slow business, with a very low success rate. The starting point for developing a new medicine is often some naturally occurring substance. Bark from the willow tree (salix) was used by the ancient Egyptians to relive pain; salicylic acid in the bark was developed at the end of the nineteenth century as the active ingredient in aspirin. Quinine had similar source: the bark of the South American cinchona tree.

It is a long road from the original inspiration for a potential drug to the final product on a shelf. Medicinal chemists have to isolate the potential active ingredient from any other chemicals it may be mixed with. It’s checked for toxicity and effectiveness in various artificial and live testbeds. It then has to be tested in a living system to see if it survives the stomach juices, and remains in circulation long enough to act. All this before starting on the question of how it’s best administered – as a lotion, inhaler, pill or patch, for example – and then to mass produce it. For all this, chemists collaborate with a range of other specialists, such as physiologists, toxicologists, biochemists and microbiologists who study the workings of the body at various levels. At a later stage, they are joined by technologists who work on the mechanics of delivery by means of a soluble pill, intravenous infusion, inhalation or diffusion from a cream or patch, for example. It’s a massive team effort.

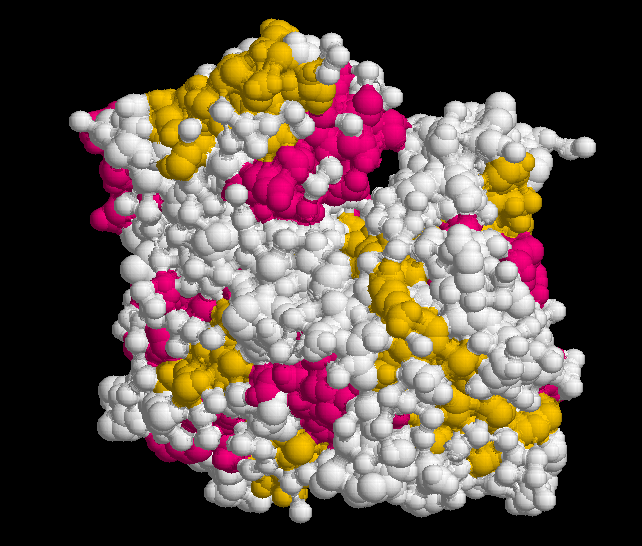

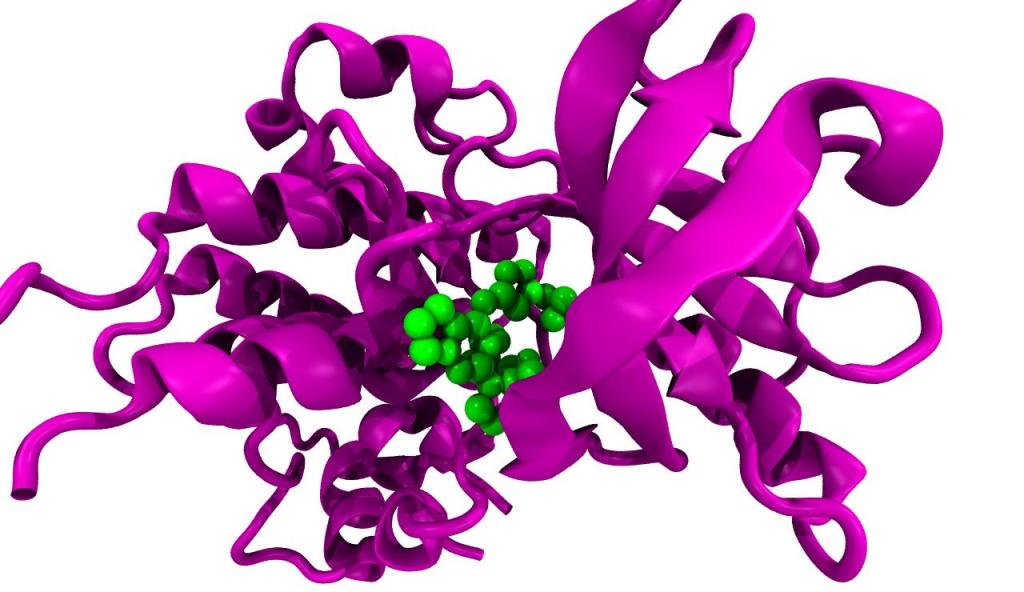

Medicines produce their effects by interacting with molecules in our bodies. The latter are often giant receptor molecules on the surface of our cells, but may also be simple substances like the acid in our stomach. The model in figure 15 is an example of an interaction.

A giant protein receptor molecule is represented as a twisting ribbon of atoms (purple) and the much smaller drug as a bunch of atoms (green). The usual functioning of a receptor is altered when a drug, hormone or other small molecule binds to it.

Figure 15 Giant receptor molecule (purple) interacting with smaller drug molecule (green)

To understand these interactions, chemists need to know about the shape of the interacting molecules and their electrical character (where their positive and negative parts are). These all influence whether two molecules will be attracted to one another and, if so, will alter each other. Understanding such properties and how they affect chemical reactions is the work of physical chemists. This branch of the subject deals with features common to all types of chemical – medicine, fuel, food or plastic – whether they are found in the body, the blast furnace or the roots of plants.

What chemicals are made of

Natural philosophers, alchemists and apothecaries experimented over many centuries with substances of all kinds, mixing them together and heating them up. In general, they had little understanding of what was going on at a deeper level, but contented themselves with observing the results. Sometimes they were able to create useful remedies from plants or to transform materials in valuable ways – bronze from copper and tin, for example. It wasn’t until the eighteenth century, however, that meticulous scientific measurements began to be taken which revealed something of the underlying mechanisms.

I now realise, some sixty years on, why the ‘law of multiple proportions’, the memorisation of which switched me off chemistry at school, was in fact so significant. It inspired its discoverer, John Dalton, to imagine chemicals as made up of atoms and led on to the concept of chemical formulae. He found that the proportions of different atoms in a chemical stood in simple ratios and could be written down using whole numbers – H2O and CO2, for example (i.e two atoms of H bonded to one atom of O; and one of C bonded to two of O). There were patterns, rather than randomness; unifying principles amidst the diversity. Thus began the mathematical and physical understanding of chemistry.

Today, thanks to the experimental work and theoretical insights of countless scientists over the centuries, we have a thorough picture of the structure of chemicals. This helps us work out how they interact with one another. At the root of it are atoms. These are not, as believed by philosophers since ancient Greek times, ultimate and indivisible. They are, themselves, made up of even smaller particles. All atoms have the same basic structure but differ in the number of particles they contain. This difference between atoms is what is demonstrated in the Periodic Table. As a wallchart in the chemistry lab, this intimidated me as a youngster at school. Later I realised it is one of the great triumphs of imaginative thinking and logical deduction by its originator, Dmitri Mendeleev. Hydrogen atoms contain the fewest particles; carbon has more, oxygen more, and so on along the rows of the periodic table. Each variety of atom is now called an ‘element’; the word implies that it is not a chemical that can be broken down any further – it is elemental.

Figure 16 Atoms of ten different elements, showing the number of electrons in each

Molecules, on the other hand are not elemental; they are made of multiple atoms and can indeed be broken down. Water and carbon dioxide are examples. In the natural world, substances we encounter may be either molecules, comprising several atoms, or just single atoms alone. Thus water, benzene and carbon dioxide are small molecules containing a few atoms of just one or two elements. Proteins and carbohydrates are large molecules made of hundreds of atoms of various elements, but copper or diamond are substances made of atoms of a single element only (carbon in the case of diamond).

If you have the appetite for more, you‘ll find an explanation of what is meant by a chemical reaction in the Read More section below, plus further examples of how chemistry impinges on our everyday life – from washing powder to paint.

Conclusion

This paean of praise for chemistry is a kind of redress for my personal failure to appreciate the subject at school. I doubt if I’m alone in this respect: questions about chemistry rarely feature in my discussions with adults, compared to those about the biology of animals and plants and the physics of our universe (plus the weather, of course).

The purpose of this blog is to try to bring chemistry into the fold. At first sight the subject seems hopelessly complicated and tedious, full of tiny points of detail about numerous kinds of substance and interactions. Thanks to great theoretical advances, however, such as the periodic table and quantum theory of the atom, a small number of organising principles has emerged to make the subject more approachable for the non-specialist. Atoms combine into molecules which interact with one another in (mostly) predictable ways. Reactions proceed at predictable speeds, either releasing or requiring energy as they do so. Theories about the basis for the various properties of substances – solidity, volatility, strength etc – are enabling new materials to be produced and processes to be devised. As our civilisation braces itself for the coming effects of climate change, nothing could be more important than knowledge of this kind. We need to understand in detail what is happening in our atmosphere, our oceans and our industrial processes if we are to limit the emission of greenhouse gases. In agriculture, fashion, construction and transport, as well as the energy sector, chemists will (mostly) be working for the good of us all.

Andrew Morris 10th February 2024

Read more….

Chemical reactions

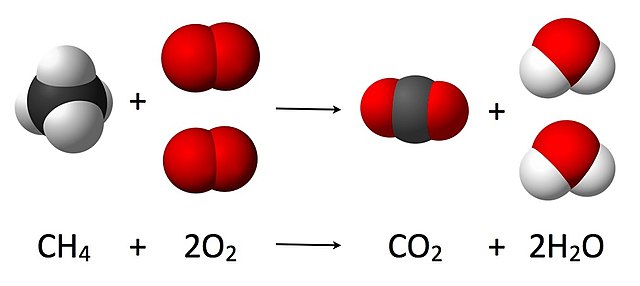

When substances interact with one another in a chemical reaction, the atoms that make up the starting materials move around and recombine to make the final materials. The total number of atoms of each element remains the same from beginning to end.

For example, when we burn methane gas in a heating system, the methane molecules are interacting with oxygen molecules in the air. The oxygen atoms from the air team up with carbon atoms in the gas to form carbon dioxide (CO2) and with hydrogen atoms in the gas to form water (H2O). That’s a chemical reaction.

Figure 16 An example of a chemical reaction: methane and oxygen

A more complex example is the process by which our bodies transform the sugar glucose, which we obtain from our food, to produce energy. Within (almost) all the cells of our bodies, oxygen from our lungs combines with the sugar glucose, derived from our food. The end products are simply water (which we excrete) and carbon dioxide (which we breathe out). This formula shows how the atoms of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen in a glucose molecule get rearranged to reappear in the water and carbon dioxide:

C6H12O6 + 6O2 à 6CO2 + 6H2O

glucose + oxygen → carbon dioxide + water

For chemists, it’s important to work out what causes molecules to interact in this way. Sometimes reactions happen spontaneously, like iron rusting in damp air; in other cases, some energy has to be given to the molecules to make them interact; this is what you are doing when you cook food or wash clothes in hot water. In some reactions, energy is actually released in a reaction, as when coal, gas or oil burn in air, once they have been ignited by a spark or pilot flame to get them above a certain starting temperature. In general, chemical reactions occur, with atoms being rearranged, when the energy of the new arrangement is lower than that of the original one. Chemicals, like all systems will shift from higher to lower levels of energy, provided they are free to do so, rather like water running from higher to lower places, provided it’s not blocked.

Atoms are held together in substances thanks to bonds between the atoms. Atoms become bonded together when their energy level together is lower than apart. So, for example, oxygen atoms usually bond together in pairs (called O2), because the energy level of the pair is lower than the two separately. The same is true for hydrogen and nitrogen atoms – under normal conditions they are not found as single atoms, always paired in molecules of H2 and N2 or in other more complex molecules.

In one kind of bond the energy level of the atoms is lower when a negative particle (called an electron) transfers from one atom to the other. This makes one atom slightly negative and leaves the other slightly positive. They are then held together by electrical attraction. This kind of bond, called ‘ionic’, is common in minerals such as common salt (sodium chloride). In the other main type of bond, one or more negative particles (electrons) are shared between the atoms. This so-called ‘covalent’ bond, is common in many everyday substances including soaps, oils and most of the molecules in our bodies – proteins, carbohydrates and DNA for example. Some atoms do not bond together with others at all. Atoms of the elements known as inert or noble gases (helium, neon and argon, for example) exist at the lowest energy level possible so do not bond together with other atoms.

Everyday processes in all parts of our lives – cleaning clothes, burning oil, digesting our food or even breathing – depend on different substances interacting in chemical reactions. Soaps react with molecules in stains to dissolve them; oils, fossil fuels react with oxygen in the air to release heat energy; enzymes break up large molecules in food; and oxygen from our lungs reacts with glucose in our cells, to energise our bodies. An important branch of chemistry studies these reactions, working out how fast they go, how much energy the release or absorb and what can speed them up or slow them down. This has led to the powerful cleaning agents, efficient combustion processes and tougher building materials we are accustomed to today. Perhaps most impressive of all are the pharmaceutical products that are extending life and freeing us from disease and pain – antibiotics, vaccines, anaesthetics and cancer drugs. The development of these has resulted from unceasing research in biological chemistry over the past two centuries. Today, not only are the broad characteristics of bodily substances – proteins, lipids and carbohydrates – understood, but the precise structures of their molecules are often known in detail. We know much about their interactions, too: how enzymes digest our food, hormones stimulate our nerves and vitamins contribute to growth. We know what cells are built of and how our genes are replicated. All this underpins our capacity to develop vaccines to destroy viruses, edit the DNA of defective genes and design chemicals that kill off cancer cells.

Chemistry in our lives – more examples

Chemistry plays a central, but often invisible role in so many more areas than those mentioned above.

Cement

Construction for example relies heavily on cement, a chemical product. It is made by extracting limestone and clay from rock quarries, pulverising the mixture and heating it in huge rotary kilns at 1400 degrees C. Chemical reactions turn the limestone (calcium carbonate ) to lime (calcium oxide), releasing carbon dioxide – contributing in a significant way to global warming. Lime and silicon-based compounds in the clay react together to form cement. Subsequent contact with water transforms the p0wder to a hard substance used in concrete and mortar.

Paint

Paint is mixture of chemicals. A binder, such as resin or acrylic, holds it together and is mixed with a solvent to make a fluid. During the painting process, the latter evaporates, leaving the binder to produce a firm surface with a gloss or matt finish. Pigments are tiny grains of coloured mineral or synthetic substances that remain in solid form, spread throughout the paint; dyes are chemicals that dissolve in the liquid medium – i.e. the molecules disperse in it. Various additive can be added to the mixture to alter its viscosity and speed up drying.

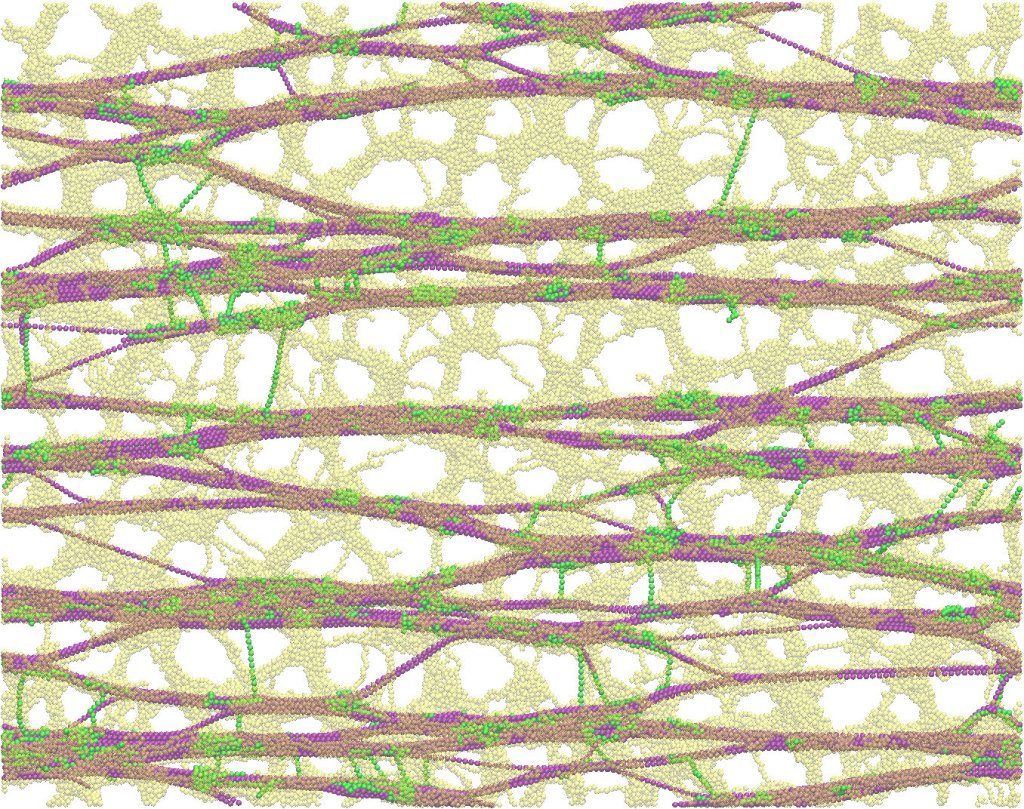

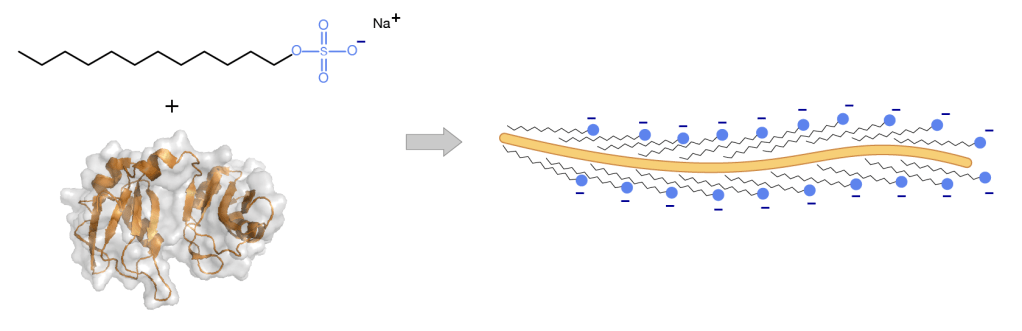

Washing powder The stains and marks in a piece of clothing are, as we know only too well, come in many forms. They may be easily soluble substance such as sugar, or a protein like egg or fat like bacon. Worst is a coloured dye as in red wine. If all are to be removed, a mixture of chemicals is needed in a detergent. First is a water softener, such as sodium carbonate, to remove minerals in hard water. Second, molecules of the main ingredients, known as surfactants, attach to the unwanted molecules of food, dirt or grease, the cluster together forming a globule that detaches from the textile fibres and becomes suspended in the water. Bleaches release hydrogen peroxide in contact with water, which goes on to oxidise organic dye stains, such as chlorophyll from grass, carotene from vegetables and tannin from tea, rendering them colourless. The more recent addition of enzymes, enable food molecules such as proteins, carbohydrates and fats to be broken up. This is the regular job of enzymes in living tissue; different kinds of enzyme are needed cleave the various types of food molecule. Figure 16 shows, on the left hand side a linear detergent molecule and a globular protein.

Figure 17 detergent molecules attaching to a protein

A protein is one long twisted, but linear molecule wrapped up into a globule – like a beaded necklace resting in the palm of your hand. A detergent molecule has a long tail that is attracted to fatty zones and a negatively charged head that is attracted to water. When the two are mixed tother the fat-loving tails of the detergent molecule link up with the fat-loving parts of the protein molecule, straightening it out, leaving the water-loving parts exposed on the outside of the combined pair. These then float off into the water, removing the protein from the fibres of the textile.

Geology, meteorology and archaeology

It’s not only in industrial processes that chemistry plays a major role; many other areas rely on its insights and techniques as important tools. Analysis of the chemical composition of surface rocks and deeper layers in the Earth’s crust, help with identifying and dating them. This is obviously important in determining where to search for minerals essential for our lives – including for the batteries that will be so important as storage of electrical energy increasingly replaces burning of fossil fuels. Understanding the geochemistry of the layers, illuminates not only our ideas about the formation of our planet, but also helps paleontologists, anthropologists and archaeologists make sense of the remains of early humans and all the earlier species that lie fossilised beneath our feet. The composition of their bones, teeth and even the meals they ate shed light on how we came to be.

The chemical composition of the atmosphere is also an important area of research, never more so than today, as we face the climate emergency. Not only do we need to understand what chemicals make up the atmosphere, but also how they are changing and moving around in three dimensions all around the globe. Acid rain, ozone depletion and chemical pollution are just a few of the issues in which chemistry has already played a vital part. Understanding how carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases interact with other molecules in the atmosphere and with the energy supplied by sunlight and lightning will be an essential aspect of the fight against global warming.

There are so many other areas of life in which chemistry plays a crucial but often invisible role – steelmaking, water treatment, gardening, art conservation, forestry, cosmetics, dentistry, desalination, papermaking, printing…. the list is endless. What an amazingly important subject chemistry is, when you take account of its application to so many aspects of our lives!