A visit from my six-year-old friend, Jamie, took me back to the joys of the playground. What rich learning environments these places are! Not only do you develop social skills like taking your turn and queuing patiently, but you’re also exploring fundamental principles of physics.

And it’s not just principles, but methods too. Jamie was consistently using trial and error to find out how things worked, and how far things could be taken safely.By repeating his trials, he was spotting consistent patterns in the way things behave and carefully assessing risks. Jamie was learning physics at pace.

A group of scientists in Sweden studied young children learning about physics in various practical situations. The study showed that the more sophisticated the children’s working theories about different phenomena in the social and material world, the more efficiently they are able to act in the world. They propose that children’s working theories about physics develop “in a space between repeating the familiar and creating something new”. It’s excitement that encourages children to extend their working theories about the material world. Their learning depends on opportunities to engage in risky play: climbing, jumping, hanging and balancing, for example. The study shows how playground experiences link with physics theory: spinning and swinging are about forces pointing towards a centre; falling and balancing are about gravity; and sliding and slipping, about friction.

Jamie was clearly grappling with all of these as he clambered up a ropework frame, flew along a zip wire and clung on as the roundabout spun ever faster. Hopefully his early learning in the playground might soon get built upon in his primary classroom in the years before him. It’s a pity the same connection between daily experience and classroom study peters out later in school life. Where better for us as adults to consider again the physics of forces, friction and gravity than by revisiting the children’s playground!

Slides and Friction

On one slide Jamie could barely move without pushing himself; but on another he raced to the bottom and almost fell off. Clearly the nature of the surface made a difference. A skating rink is the most extreme example of a low friction surface.

Figure 1 a typical slide

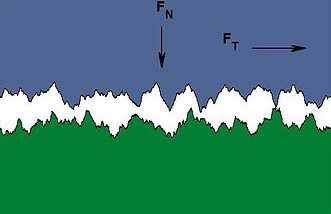

Friction, as we soon learn, is all about the smoothness of two surfaces at the microscopic level. Less obvious to the naked eye, however, is just how rough they are at the microscopic level. In profile the two surfaces look almost like mountain ranges (figure 2), only touching occasionally where their peaks met.

Figure 2 diagram of two surfaces in contact

Sliding friction – when a force pulls one surface across the other – is the result of having to force these jagged peaks past each other. The precise cause of friction is not fully understood, but involves some forcing of peaks past each other and some breaking of chemical bonds between close atoms on the two surfaces.

The “laws” of friction taught at school are based on experiments rather than theory. They show that the strength of the frictional force (FT in figure 2) depends directly on the amount of force pressing the two surfaces together (FN in figure 2). Again, we learn from experience that it’s harder to shift a heavy box across a floor than a light one.

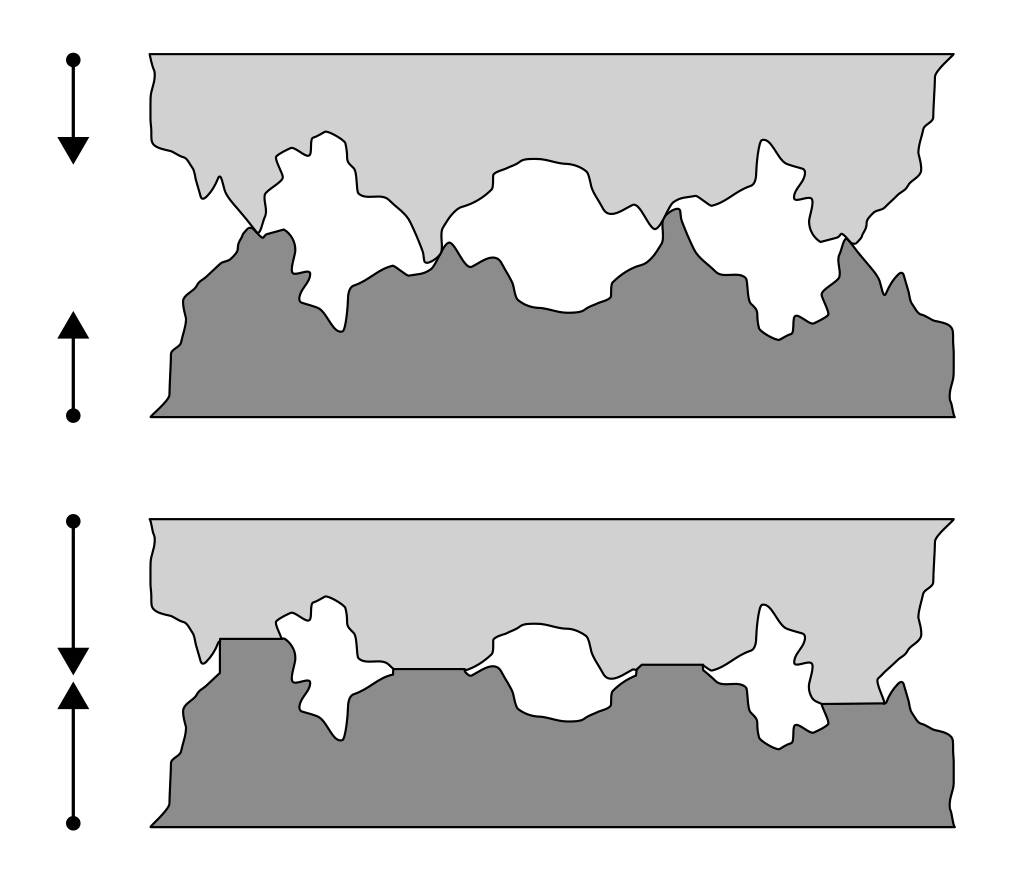

This is hardly surprising when you consider the crushing effect on the microscopic peaks shown in the lower half of figure 3. The effective area of contact is increased when two surfaces are pressed together.

Figure 3 surfaces in contact before and after loading

The amount of frictional resistance doesn’t only depend on how tightly the surfaces are pressed togther; it also depends on what they are made of – as everyday observation shows. Shiny metals may run past each other more readily than rough stone, for example, or silk cloth compared to wool. . The frictional quality of a surface (the coefficient of friction) is measured experimentally and is a vitally important quantity to know about in the design of engines, skis or even clothing.

An interesting point that you may have noticed when you want to slide, is that it seems to take more force to get yourself started than is needed once you are moving. This is generally true – the coefficient for sliding friction is little lower than for static friction. At first, the idea of static friction may seem a little odd – surely friction only arises when one thing moves over another, like rubbing with sandpaper? A moment’s reflection, however puts us right. You can put a book on a gently sloping surface and its stays put, up to a point. Friction is preventing it from slipping down the slope, although nothing is moving – yet. But if the slope become too steep, a point is reached when the static friction is insufficient to prevent the book sliding under gravity. Thereafter it slides easily, without stopping again, as the frictional force is reduced when sliding.

Another case of static friction, slightly less obvious, is the point of contact between a tyre and the road. Where the two meet, a tyre is not actually moving with respect to the road surface, but the frictional grip is vital if the vehicle is to move forward. Ice or oil on the road reduce its frictional grip. That’s why material like rubber, with its high coefficient of static friction, is used for tyres.

Slides and gravity

But of course, it’s not only the surface of a slide that matters – what about how steep it is? A six-year-old will be busy working out that you’re more likely to go faster on a steep slide. What’s the physics behind this?

The force due to gravity, as we soon learn, always acts downwards – towards the centre of the Earth. That’s why things fall vertically, if free to do so. But what if there is something in the way like a table, the floor, or the surface of a slide?

Figures 4 and 5 help explain this. A book resting on a table (figure 4) or anyone or anything standing on the floor, manages to stay still because the force of gravity acting downwards induces an upward reaction force in the table or floor which exactly balances it.

Figure 4 Reaction force opposing gravity

When the surface on which something rests is inclined at an angle, however, the direction of the gravity and reaction forces are no longer opposed (figure 5)

Figure 5 Force due to gravity, on a slope.

In this case we imagine the gravity force (Fgrav) to be composed of two parts, one acting down the slope (FII) and one pressing into the surface (F ̝ ), inducing a reaction force (not shown). In this way we can see there is now a smallish part of the gravity force tending to push down the slope.

It’s interesting that slides generally flatten off gradually towards the bottom as in figure 1. Again, experience tells us that this will slacken the speed to provide a safe return to ground. But what does this tell us about how forces affect speed? After all, you’re at rest when you start and also at the end; what exactly happened in between?

It’s easy to see from the diagram that the steeper the slope the greater is the component that acts down the slope and the smaller the part that presses into the surface. Launching off from the top of a slide, the downward part of the gravity force is sufficient to overcome the friction force, so Jamie slides down happily. If the slope is not steep enough however, the component of force pushing him down the slope is too weak – less than the frictional force opposing motion – so Jamie gets stuck and, no doubt, irritated.

Speed and acceleration A close look at the slide in figure 1 (or any other one) shows the shape is flat, or nearly so, at top and bottom. Where it’s flat, there’s no forward force at all directed along the slide. On the main part of the slide, however, a component of the gravity force acts along the slope, opposing the inherent friction force. If this component is large enough it will overcome the friction, providing a net force acting along the slope. So, we need to find out what happens to the motion of something when there is a net force acting on it. This is what Galileo set out to do, back in the year 1600.

In an ingenious experiment, he carefully observed balls rolling down an incline, as shown in figure 6.

He first let the ball run all the way down; then only half-way; then a quarter. He found it speeded up as it rolled down the slope, covering a greater distance each second.

He went further and showed that the distance it travelled increased as the square of the time taken. i.e. if it travelled one meter in one second it travelled four metres in two seconds, nine in three seconds and so on.

Figure 6 Galileo’s experiment on an incline

In figure 6 you can see little bells attached to the incline, which ring as the ball passes.They are carefully spaced so the distance between each, increases as the square. You then hear the bells ring at equal intervals of time as the accelerating ball passes.

As an interesting aside, accurate clocks hadn’t been invented at the time of Galileo’s experiment. So, to compare the time it took to descend on each occasion, Galileo let water pass into a jar while the ball was in motion, then weighed the amount of water passed!

The ball was clearly accelerating, not just moving steadily. This discovery was in flat contradiction to the prevailing laws of natural philosophy, handed down from the Ancient Greeks. He had shown that a steady force doesn’t just keep something moving, it steadily accelerates it.

From this discovery, Isaac Newton, was able to formulate a “law” that, if there is a net force acting on something (i.e. after friction has been overcome), it will not only move, but will get faster and faster. Thus, Jamie’s descent from the top of the slide goes like this: he starts from rest; then a gentle shove gets him started, then with a net force down the slope he accelerates as he descends. Where the surface begins to flatten off towards the end, the net force down the slope weakens until there is none at all on the final flat section. The frictional force then decelerates him till he comes to rest (hopefully).

This detailed explanation may seem rather elaborate for what is pretty obvious from everyday observation. What is less intuitive, however, is the full implication of Galileo’s discovery or Newtons “law” as it became known. If a net force produces acceleration, what happens when there is no net force? Everyday experience on Earth suggests there will be no motion at all. That indeed is what the ancient philosophers believed – force is required to maintain motion. Newton showed if there is no net force on a thing, it doesn’t speed up or slow down; it just keeps doing what it was doing: either remaining stationary or moving forward at steady speed in a straight line. For steady motion, no net force is required.

Thanks to space exploration we now know this really is true. In the void of outer space there is no friction or air resistance because there is nothing there. This enables space vehicles to hurtle through space to distant planets and moons without any force to drive them. One is now out beyond our solar system, passing forever through the emptiness beyond. Spacecraft need an initial thrust to get them away from Earth’s gravity and to speed them up; thereafter they simply carry on cruising at a steady speed, towards their destination, burning no fuel, with no air to resist them. No net force: steady speed.

Roundabouts and ‘centrifugal’ force

Talk of force in a children’s playground brings to mind the strongest and weirdest sensation of force: the sense of being thrown outwards on a fast-moving roundabout. It can make you feel quite giddy. It’s common to call this force ‘centrifugal’ after the Latin for ‘fleeing from the centre’. That indeed is exactly what it feels like. You grip on tightly to the rail to pull yourself inwards against the tendency to be flung off. Contrary to intuition, however, you wouldn’t in fact be flung off outwards away from the centre, even though that’s the direction you are pulling inwardly against.

If you were to suddenly let go (as in figure 7), you would simply keep moving in the direction you were travelling in at that precise moment: i.e. along the tangent. When we grip tightly on the rail, we are simply pulling ourselves inwards, away from the line of the tangent.

Figure 7 Moving in a circle

This continuous pulling inwards towards the centre ensures that we are continuously changing our direction as we rotate around a circle. Figure 8 shows how an object that was originally travelling in a straight line (position 0) has to be continuously forced inwards (red arrows in positions 1, 2, 3 etc) if it is to end up moving in a circle.

Figure 8 A moving object being forced into circular motion

This is the way satellites are manoeuvred from a straight path into an orbit, using little side-thrusters to nudge them into a circle. It’s also how moons get captured by planets and planets by stars like the Sun. Gravitational force does the nudging. Isaac Newton made the giant leap of realising that all forces had the same effect on motion, whether they were gravitational forces holding the Moon in place, muscular forces pulling things forward or frictional forces slowing things down. He summarised the rule about unbalanced forces: they either speed things up, slow them down or change their direction (or a bit of both).

Out in space, this is how satellites, planets and stars respond to the gravitational forces they exert on each other.

They just keep revolving round and round, with no air to slow them down. Gravity provides the centripetal force needed to keep them constantly changing direction as they move around their orbits.

Figure 9 Planet or satellite or Moon orbiting

Orbiting, as depicted in figure 9, follows the same principle whether it’s a satellite around the Earth, a moon around a planet, a planet around a star or even whole galaxies, around each other. Here on Earth, however, where motion is always opposed by friction or air resistance, forces have to first overcome any resistance before they can alter the speed or direction of objects.

A different example of a force directed toward the centre is a swing, found in every playground. Rather than pointing towards the centre of rotation, however, as in a roundabout, it points towards the centre of oscillation. This is explanined graphically under Swings and oscillation in the Read More section, below.

See-saws and turning forces

As we know, forces not only drive things forward or round a circle or back and forth, they can also turn things around a pivot. Take the case of the see-saw.

It can be tricky in a children’s playground, pointing out that a big child and small child sitting at each end just won’t work. They’ll stay grounded, unless the big one works out how to shift forward along the plank. These two in figure 12 haven’t quite got it.

Figure 12 balance on a see-saw

Everyday experience of door handles and garden shears teaches us about the turning effect of forces. The further a force is applied from a pivot, the great will be its turning effect. The word ‘torque’ is used to capture this. It’s simply the force times the distance from the pivot. So, a big child nearer the pivot can balance a smaller one further away – they both exert the same torque or turning effect.

The old device for weighing heavy sacks showed this principle beautifully (figure 13). Called a steelyard (or Roman balance), it is suspended from a hook. The small weight is shifted along a bar until it balances a heavy load – such as a sack of flour – suspended from the lower hook, which is positioned very close to the pivot.

Figure 13 A steelyard

The turning effect of the heavy sack is balanced by the opposite turning effect of the more distant weight. Graduations along the bar give the weight of the sack. This is the principle of the lever, which enables a moderate force to have a large turning effect, or torque, by moving it further away from the pivot. It influences the design of so many everyday devices, from a steering wheel to a pair of scissors.

Conclusion

A children’s playground was the inspiration for this exploration of mechanics, but the principles it illustrates apply to so many aspects of experience, from driving a vehicle to opening a can of beans – or even how we move. The subject can come across at school as both diffcult and boring – especially in our teenage years. But, once anxiety about complicated diagrams, with their intimidating labels and technical terms is overcome, it’s a topic that is both fascinating and useful in everyday matters.

© Andrew Morris October 2023

Read More

Swings and oscillation Another example of a force directed toward the centre is a swing, found in every playground. Rather than pointing towards the centre of rotation, however, as in a roundabout, it points towards the centre of oscillation.

In the animation on figure 10 you can see how the force of gravity (labelled ‘mg’ in the diagram) always pulls vertically downwards, but the tension in the chain or rope (labelled T) partly points in towards the centre and partly balances the gravity force (or weight).

Figure 10 swinging motion

The connection between the circular motion on a roundabout and oscillating motion on a swing is nicely illustrated in figure 11.

The red dot represents a person on a roundabout; the blue one approximates to a person on a swing (at low amplitude).

Figure 11 circular motion and oscillation (swings and roundabouts}

If you are trying to push a child on a swing, you’ll know that the point at which you give a shove is important. Time it right, and the force you apply adds to the force from the chain; this amplifies the swing. Get it wrong and your force will oppose that of the chain, and you’ll damp down the motion. The first case is an example of resonance, where the energy you feed amplifies the motion; the latter is a case of damping, as used to cut down vibrations – on car wheels or wobbly bridges, for example.

Energy and the Zip wire

So far, we’ve described motion on playground equipment in terms of the forces acting on a person – gravity and friction, mainly. It is equally possible to describe the same processes in terms of energy.

Figure 14 shows the energy changes in a swing. At the high point A where, for an instant, movement stops, it is entirely gravitational. At the lowest point (B), this energy has been converted into energy of motion (called ‘kinetic’). Some energy is lost in the bearings, thanks to friction, but overall, the total energy remains the same; it’s just the type that changes.

Figure 14 energy changes on a swing

Figure 15 Zipwire

In a playground zip wire, a child gains energy by climbing up against gravity on to platform. Then hurtling down the wire, the child loses some of this of gravitational energy but gains kinetic energy, eventually crashing into rubber tyre. In this soft collision the tyre compresses, absorbing the energy of motion, then as it rebounds, it returns some of the energy to the child, who begins retracing their path.

The child doesn’t return all the way, however, as some of the energy was retained in the tyre, slightly heating it up as it regains its original shape.Overall, the sum total of energy remains constant throughout this, or any other, process – it merely changes its form: gravitational → kinetic → heat, for example.

Physical processes can be described equally in terms of the action of forces or the changes in energy that occur. They are equivalent – just two ways of describing the same phenomena.