It all began with talk in a science group about people with extraordinary abilities. Patrick had seen a conductor take an orchestra through an hour-long symphony with no written score to guide him; he clearly knew every note of the piece by heart, for each of the sixty-odd players.

Another case, captured in a TV documentary about a prodigious child, showed a remarkably detailed and accurate drawing he’d made from memory of London’s St Pancras Station, a notoriously elaborate Victorian building. “What accounts for such extreme aptitudes?” asked Julie.

The abilities of such so-called savants appear to fall within a fairly narrow range – music and drawing, plus maths and calendar counting – more specifically, in skills such as perfect pitch, phenomenal calculation and knowing the day of the week for any given date. The group discussing this intriguing topic wanted to know how such extreme aptitudes arise. Are they feats of exceptional memory? Why do so few people have them?

Savantism

Studies suggest that these exceptional abilities are associated with the wider condition of autism. One theory suggests that the phenomenon is characterised by extraordinary sensitivity to repetitive patterns and attention to detail. Another suggests it may be the result of the creative and imaginative right hemisphere of the brain compensating for some kind of dysfunction in the logical, reasoning left one.

Regions of the brain may be exceptionally richly interconnected and there may be differences in the structure of the white matter deep in the brain. Savants’ brains may be processing low level information that is ordinarily filtered out from the mass of incoming signals to which we are continually exposed. Extreme cases of savantism are very rare indeed, but the sheer fact that memory capacity for a very few can be so much greater than for most of us, reveals the great untapped potential of the human brain. Little is known for sure about why this amazing resource is restricted to so few exceptional individuals.

Retrieving memories

At first, we may imagine our memory as a kind of vast storage area or filing system, in which each particular item gets stored away indefinitely, as in a computer. But, as we all know only too well, we can also forget things. The act of remembering necessarily entails some way of retrieving the stored memory. One type of forgetting is simple: the original information was never fully stored in the first place, so can’t possibly be retrieved. You may remember roughly what a bank note looks like but not be able to recall the exact images and text on it, because you hadn’t internalised that information.

More baffling is the situation in which you know you have stored a memory but just can’t bring it to mind when you want to – it’s ‘on the tip of your tongue’. Psychology experiments show that cues are needed to retrieve memories. These are associated with the situation surrounding the laying down of the memory and are laid down alongside it. A familiar example is the power of a smell to bring to mind an experience – ‘mothballs’ was the example Sarah brought to the group, reminding her of her grandmother. If the cue is missing, the memory is harder to retrieve. In one unusual experiment deep-sea divers memorised a long list of words while still on dry land. Half of them then went deep underwater and half remained on the beach. When tested where they were, those who remained on land were 40% better at recalling the words than those who had dramatically changed their surroundings, so were lacking the environmental cue.

Learning new things

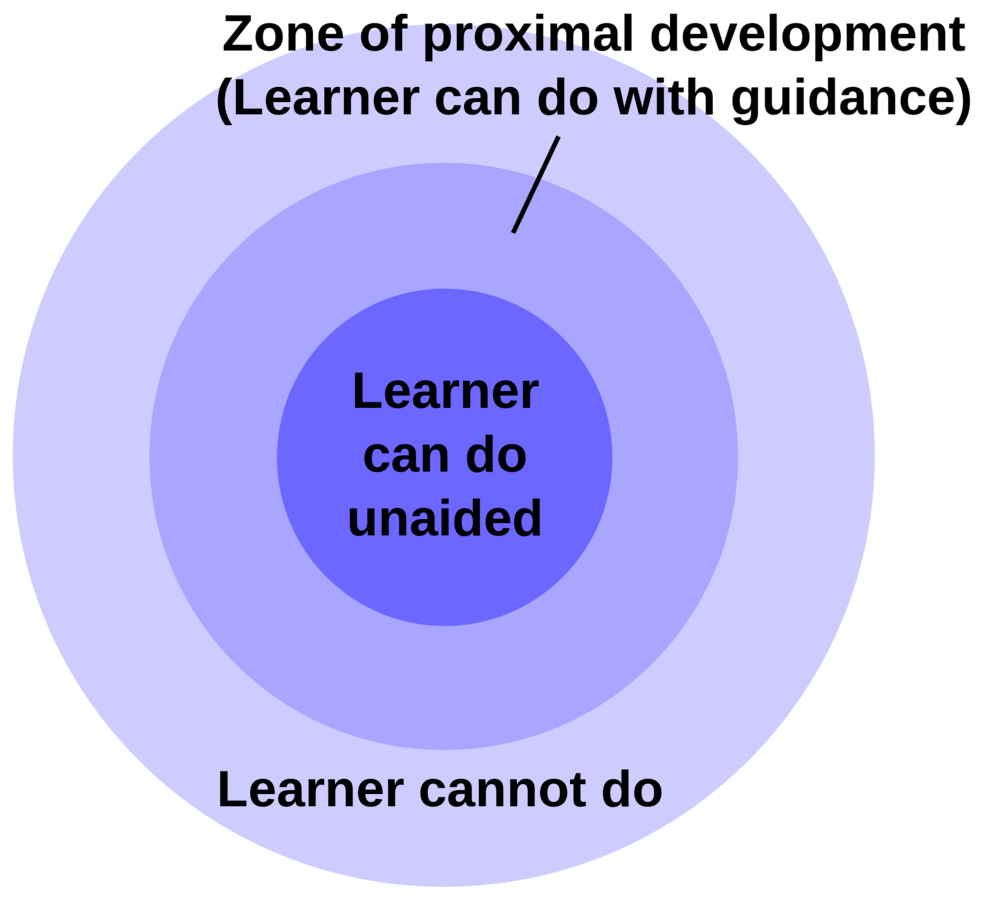

At this point in the discussion, Sarah in the group began thinking of her own experience of learning maths. She’d been quite good at it in primary school but lost the appetite for it as she moved through secondary; new material seemed too baffling. In my experience as a former maths teacher, this is common. The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky established a key idea about effective learning. He saw that two opposing challenges face the learner tackling a new idea: on the one hand, being fed material you already understand is tedious and easily leads to distraction; on the other hand, new concepts that lie too far away often lead to frustration, even anger and rejection if it’s a regular occurrence.

The art of the teacher is to find the ‘sweet spot’ – dubbed the ‘zone of proximal development’ by Vygotsky – that is sufficiently challenging to motivate learning but close enough to previous understanding to be taken on board. For most of us, it takes time and repetition before strange new concepts become familiar and useable.

Figure 1. The ‘ Zone of proximal development’

A moment’s observation of a baby or infant shows just how expert they are at persisting with such repetitive tasks until they are satisfied. For early teenagers, however, as Sarah quickly reminded the group, patience and persistence don’t always come so easily.

“What about self-discipline?” interjected Julie at this point; “where does that come from”. She was an avid follower of tennis and knew that constant repetitive practice was a distinguishing feature of top players. Patrick knew the same was true for musical performance – experts, who seem so naturally gifted, invariably attribute their skill to intense practice. We now know more about the reason for this.

It’s the connections between nerve cells (neurons) that really matter. These create pathways through the individual cells of the brain, and these link to our sensory organs and our muscles and hormone systems.

figure 2. Model of neurons connected together

Our memories are stored and actions taken by means of these pathways. Studies have revealed that these connections get reinforced every time they are used; and, conversely, they can fade away if not used. So repeated activation of a pathway strengthens the connections. Over time, this strengthening results in what we experience as secure, long-term memory and behaviour that has become automatic. You drive absent-mindedly along a well-known route for this reason. It’s also how we are able to build exceptional skills with repetitive practice, whether in tennis, musical performance or any other area of competence.

But as the tennis fan in the group pointed out: “you do need a teacher who can make practice fun. Andy Murray’s mother did this”. Fun or not, you surely need a degree of self-discipline as well, to persist with repetitive practice. “Where does it come from?” asked Sarah. “Why is it easier for some?” For Marian it was the all-too-human opposite that came to mind: “what about laziness” she asked? “Does it really exist – or is it really a cover for other emotional issues?

The main theory of self-discipline or will power or persistence suggests that whatever it is that’s driving it tires with use. Experiments have been designed that test people’s self-discipline after they have been put through a challenging task. These demonstrated that exertion weakened the self-discipline of those who undertook the prior task, compared to others who didn’t. It’s like a muscle, fatigue sets in with use. Self-discipline requires gratification to be delayed and impulses to be controlled. In other words, it’s linked to our ability to manage our emotions and make rational decisions, despite temptation. In delaying gratification, the brain is estimating that it’s likely the eventual payoff will be greater if an immediate reward is put off.

The well known ‘marshmallow test’ shows that most children under four are simply unable to resist the temptation of one marshmallow now, even with the promise of two later if they can hold on. As adults, we too may still struggle with this; but thanks to the strengthening of neuronal pathways that comes with repeated use, it gradually gets easier with experience. In acquiring skill, your brain learns that the pleasing flush of success may well follow if you keep going with repeated practice. In effect you are gradually developing a new habit.

As is obvious from everyday experience, individuals vary in their ability to hold off in this way. The cause of this variation in self-discipline seems to lie both in the genes you inherited from your parents and in the environment in which you grew up – neither of which you have much choice about! When family norms are consistent and autonomy is encouraged, children develop self-discipline, particularly when it is being modelled by the adults around them.

As Marian had pointed out earlier, this explanation of self-discipline does raise the question of its nemesis – laziness. Is this best understood as a moral issue, is it something that can be beaten out of you by authoritarian methods? Research in neuroscience suggests otherwise. The ability to delay rewards is, like all biological processes, fallible. The bodily mechanisms that drive motivation don’t always perform optimally. People who were once highly motivated can lose this capacity when the relevant area of the brain is damaged – for example by a stroke. Studies show that the role of the hormone and neurotransmitter dopamine is key to this. It drives both our sense of pleasure and the feeling of wanting something. A well-functioning dopamine system gives us the desire to act in pursuit of a reward. In one documented case, a normally motivated patient who’d suffered a stroke became uncharacteristically apathetic. After treatment with a drug that activates dopamine receptors, their motivation recovered.

People loosely described as ‘lazy’ appear to feel that any potential reward is too small for the amount of effort they believe is required to secure it. Therapies for this attempt to reduce the sense of effort required, by for example replacing a series of separate decisions that need to be made with a routine that involves fewer decisions. Equally, therapies may be designed to enhance the perceived value of a reward by, for example, linking it to something that is meaningful for, and gives pleasure to, the individual. Moral pressure isn’t generally found to be a successful approach!

Conclusion

Having explored something of the biological basis of self-discipline, the discussion group reflected on their own experiences of the difficulties of exercising it in real life. Julie, for example had been brought up with strict discipline as a child which she accepted. As soon as she got to university however, she used her new-found freedom to rebel against it, at least for a while. Sarah emphasised the importance of trust, an essential element if you are risking an immediate reward in the belief that a better one will follow later. Trust of this kind is not available for everyone in every situation. A more obvious problem was highlighted by Marion: “practising the same thing over and over again can just get boring” she reminded the group. As Julie pointed out: “procrastinating can really be a way of putting off what makes you feel bad. It’s all about emotion”.

It’s clear that psychology and neuroscience do not have all the answers to why a tiny number of people possess such extraordinary powers of memory and recall, while the rest of us unwittingly filter out the vast bulk of the detail hitting our senses. Perhaps we ought to be thankful for the gift of routine forgetting; after all, it does save us from a head full of clutter!

© Andrew Morris January 2026