For the first time in her life, Julie was spending big money – she was doing up her flat in London. For a person who had worked hard all her life, earning a moderate salary, this was quite a moment. It triggered a long discussion in her science group about our spending and saving habits. Before long the issue of wealth became the focus of discussion, and then the rise of the super-rich.

Inexorably, the whole question of inequality followed – why does it exist, how did it come about? What light can science throw on the topic?

Patrick recalled his 50s childhood when money was tight; saving up pocket money to get a bigger bit of railway kit became a lifelong habit. Marian still feels slightly guilty when she spends on clothes; Mary always faces a dilemma booking a hotel – how expensive should I go? We all knew people who seemed a bit over the top, either way and wondered what it is that makes some individuals happy to spend as though there’s no tomorrow, while others hold on tight in fear of disaster around the corner. “Maybe buying things gives you a sense of achievement – I’ve got something” said Sarah, adding “perhaps it’s the feeling of control – I’ve done something within my powers …. I guess it gives you a kind of a dopamine kick”. Now retired, Patrick saw his childhood habit as becoming rather anachronistic – “why save for the future when you are in the future!”

Spending or saving

Research in psychology explains quite a few of the factors affecting our spending habits. As most of us, especially parents of small children, know from personal experience, we tend to prefer immediate rewards over delayed ones (It’s called ‘delay discounting’).

As a notable experiment showed, given the choice between one marshmallow now or two in 10 minutes time, children under four simply cannot resist the temptation. Two parts of the brain are in conflict, but one is not yet fully developed. The reward system, mediated by the hormone dopamine, processes immediate pleasure, while the still underdeveloped prefrontal cortex struggles to overrule it, in the interest of longer-term goals. The conflict remains to some extent throughout adult life.

Another bias to which we are prone is the tendency to favour immediate rewards and underestimate the need for future savings, the ‘present bias’. Difficulty in persuading people to sign up for a pension is an obvious example of this. Salary systems that deduct pension contributions automatically from your pay packet are clearly designed with this in mind. Supermarkets make play of yet another natural bias we all have: the tendency to be overly impressed by the first piece of information we encounter when making a decision. An item once priced at £100, but now reduced to £50, gives you a sense that you’ve saved £50 rather than spent £50.

Emotions, particularly anxiety, can also affect our tendency to spend. Excessive stress can lead to a short-term approach to financial decisions rather than long-term planning. Research in the University of Minnesota shows that stress associated with an upbringing in a poorer household is associated with a more short-term, opportunistic orientation to life with less concern about long-term consequences. There is a suggestion that this tendency may be rooted in our evolution as a species: for early humans, taking what you could get now may have proved advantageous at a time when the future was so uncertain.

Neuroscience has added to what has been found from psychology experiments. Research on the brain shows that spending money can trigger the same reward pathways in the brain as eating delicious food, gambling or absorbing addictive substances.

Figure 1 The reward system in the brain

Equally, losing money may activate the brain’s pain centres, making financial loss feel physically distressing. In other words, we can be driven to spend not only by tempting advertisements, supermarket promotions and hard-wired habits, but also by the pleasure-seeking tendency common to drinking and gambling.

Social factors

Social factors also play a part: we tend to evaluate ourselves by comparing ourselves with others. We might be tempted to spend simply to keep up with the lavish lifestyle of others, or we may be repelled by it and adopt an opposite tendency. These social effects differ across cultures: in collectivist ones, individual savings are of less importance than taxes to pay for universal social services, whereas more individualistic cultures may encourage people to save aggressively for their own security.

Research on happiness throws light on the feelings associated with spending and saving. A website offering advice to business investors concludes that cautious investors may enjoy a deep-rooted sense of peace and satisfaction from their financial security, freedom from debt, and ability to cope with life’s ups and downs. People with long-term financial stability report higher life satisfaction due to reduced financial stress. Delayed gratification is linked to better mental health, higher financial stability, and overall well-being. Big spenders, on the other hand, may experience immediate joy from luxurious purchases and high social status, but then face the challenges of maintaining their lifestyle and adapting to ever-increasing standards. They can get caught in a cycle where each new purchase only brings temporary happiness, compelling them to seek more extravagant buys to feel the same joy: as they earn more, they spend more, making it challenging to find satisfaction as their standards rise.

Wealth inequality in history

Curious about the origins of this unsatisfying cycle of wealth accumulation, the group’s attention switched from today’s world to the incredible wealth uncovered by archaeologists in ancient civilisations. “People like the pharaohs grew wealthy on the back of others” Patrick recalled. But why did the poorer people allow the rich to exploit them? Was it just violent coercion or something in us that wants us to ‘know our place’? As Marian pointed out “societies have foundational myths about hierarchy, royal blood and divine right “. How did these myths arise?

Chapter five of a book that had inspired Sarah, Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari, opens with a description of the agricultural revolution, the point at which hunter-gatherer culture gave way to cultivation of crops and breeding of livestock. It describes this historic turn of events with the surprising phrase “history’s biggest fraud”. It explains that for most people this economic revolution meant a lifetime of hard and repetitive work, while at the same time, a small minority came to claim ownership of previously common land and the right to pass it on to their descendants. Far from a great step forward for all, it marked the beginning of inequality on a massive scale. Lasting divisions between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ can be traced back to the Neolithic or late Stone Age, kick-started by the first farming machinery, the ox drawn plough. With the increased productivity brought about by the new technology surpluses could be generated, enabling some to rise above subsistence. More lived for longer, had more children and, as a result, populations rose. Villages, and later towns, grew and new roles become possible, unrelated to work on the land: priests, soldiers and artisans could be supported on the surpluses of a more productive economy. With larger settlements, the bonds of kinships were no longer sufficient to hold societies together. New forms of social hierarchy developed in which those with land assumed dominant roles. To hold these larger communities together myths developed to which all had to subscribe, and mythical beings were invented to provide these leaders with a claim to divine authority.

To get a grip on these historical changes, the group looked to archaeology to see what light it could throw on how such inequalities of wealth came about.

An article in Smithsonian magazine reports on a study of dwellings in ancient sites which compared their size over time, using this as a proxy for degrees of wealth. From this data, wealth inequality was estimated to have increased steadily over thousands of years since the onset of agriculture around 7000 years BCE. It peaked in ancient Egypt around 1930 BCE, fell back in the early centuries of the first Millenium, then grew again, reaching a new peak in the USA today.

Figure 2 Gold sandals from ancient Egypt in the 1400s BCE

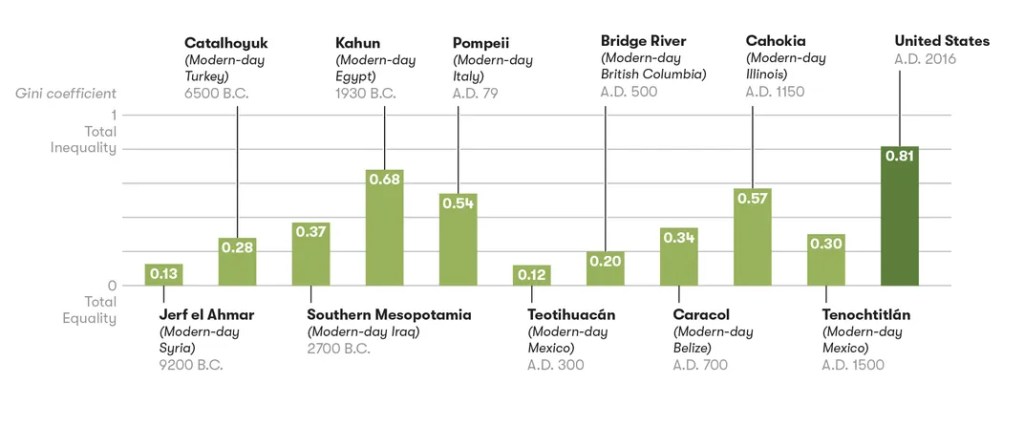

Figure 3 is a graph from the Smithsonian magazine which shows this, using a statistical measure of wealth inequality known to economists as the ‘Gini coefficient’.

Figure 3 Timeline of wealth inequality (image credit: Matt Twombly)

It charts the degree of inequality over time, highlighting the eras of key civilisations. By linking these estimates of wealth inequality with historical information about the state of technological development it was possible to show that the more technologically advanced a society was, the less equal it tended to be.

The super-rich

Struck by the relevance of this to today’s world, Marian turned to the question of today’s super-rich: “what about professional footballers and actors who earn phenomenal money” she asked. “What’s driving them – is it about greed; money is never enough?”. Mary chipped in: “some donate to charity, like supporting schools in deprived areas, but is that just a way of coping with being very rich?” Julie brought in a political perspective: “What about Scandinavia where people accept high taxes in return for a caring society”. “Some seem to perceive the world as hostile, so the priority is to defend yourself; others see the benign side of humans and have a trusting view about pooling their resources” Patrick responded. “Why do the superrich keep on making money instead of enjoying an easy life – isn’t it about power? Isn’t it addictive” asked Sarah, to which Mary added a further dimension “surely it’s also about competitiveness – being the richest”.

Research tends to confirm these intuitive explanations in terms of addiction and competitiveness. An American journalist decided to look into this question by interviewing a number of super rich people as well as some researchers who had studied them. He found them to be primarily concerned with two simple questions: am I doing better than I was before, and am I doing better than other people? Their relative position in a global league table was of greater importance than the absolute value of the things their money could buy. Over time such concerns can only move you upwards, in a kind of ratchet effect. When you make a bit of money you move to a wealthier neighbourhood, but once there, surrounded by even richer people, you feel you’re at the poorer end of your new community – you need to get richer still. One of researchers interviewed said: “every billionaire I’ve spoken to is extremely excited by each additional increment of money they make” and they ask themselves “do I have as much or more than these people I’m comparing myself with?”

Conclusion

Inequality in wealth today is extreme and steadily growing. Research at the London School of Economics shows that in the eight years from 2011 to 2019, the poorest 10% of households had no wealth at all and the top 10% became £280,000 wealthier over the period: the wealth gap in the UK grew by 50% over these eight years. A study by Kings College London considered the consequences of this growing wealth inequality, concluding that it could be a “major driver of societal collapse” within the next decade, “undermining social cohesion and a risk of further deterioration without intervention”.

This blog has looked at the deep roots of inequality through the work of psychologists, neuroscientists, sociologists, economists and archaeologists. It has addressed the question many of us ask, about why millionaires still ache to be billionaires and, even in one case, a trillionaire. It shows how the dilemmas about spending or saving, to which we are all subject, are reflected in the interplay of different parts of our brains. The stress of growing up in impoverished households aggravates impulsive tendencies and inhibits longer term thinking. Balanced attitudes to getting and spending are going to be essential if the planet is to be secure from the ravages of climate change, pollution and plutocracy. Wealth must surely be distributed more fairly to secure a future for all.

© Andrew Morris November 2025