Having discussed the book Ultra Processed People by Chris van Tulleken, one science group started getting to grips with the baffling world of food additives, as described in part I of this double blog. In part II, we explain briefly what is meant by words like emulsifier and antioxidant, with a view to better understanding what it is we are consuming and whether it poses a risk to health.

Stabilisers

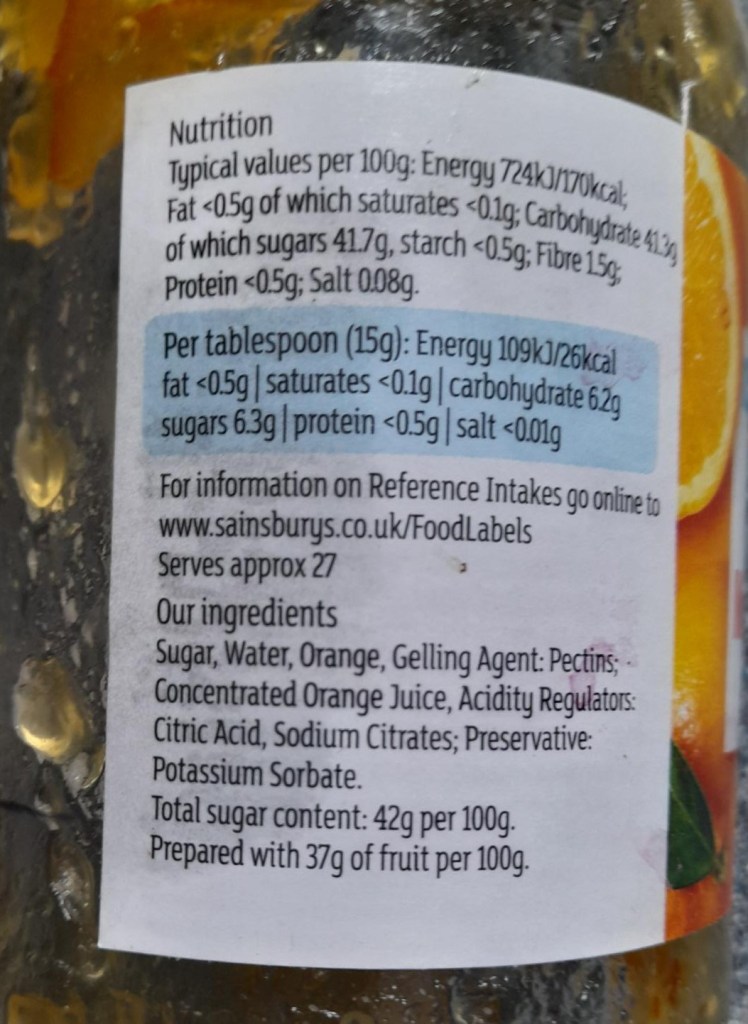

Stabilisers are substances used to prevent ingredients separating in mixtures. They are used in oil-water combinations like salad dressing or in frozen foods, such as ice cream, where water tends to crystallise out. They are also used in jam and yogurt to prevent fruit from settling. Pectin is a natural stabiliser found in fruit, which helps jam gel. It’s a large molecule that helps keep the walls of plant cells firm. Carrageenan and agar are other nature-based kinds, both derived from seaweed. Guar gum is produced from the guar bean and is generally considered safe; Xanthum gum is produced industrially through fermentation by bacteria.

Emulsifiers

‘Emulsion’ – more familiar in the paint shop than the supermarket – means a liquid made of parts that don’t ordinarily mix – like oil and water.

In the case of paint an oily polymer containing the pigment is mixed with water to help spread the pigment.

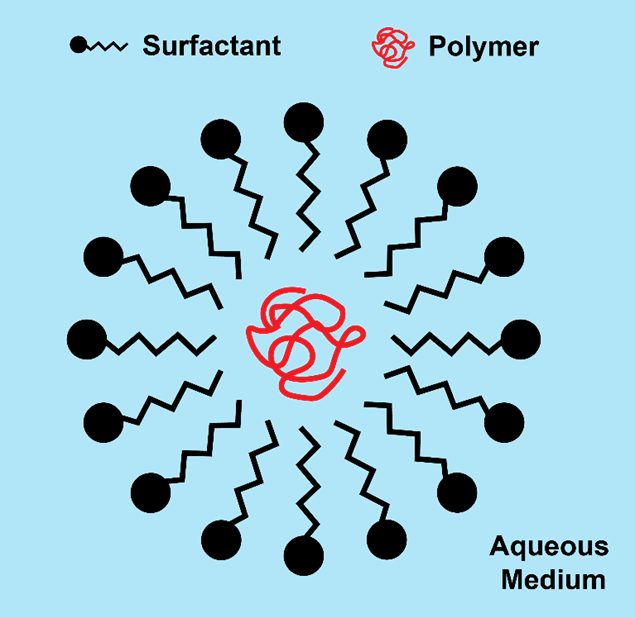

An emulsifier (labelled surfactant in this diagram) links the incompatible parts, by having two different ends to its molecule – an oil-friendly one (wiggly line) that clings to oil molecules and a water-friendly end (round blob) that faces the surrounding water.

Like paint, many foods have a double character, oily and watery, so are also emulsions. The classic example is milk, with its globules of fat dispersed in a watery medium. Margarine is another example, in which watery material is dispersed in an oily medium.

‘Emulsifiers’ are often added to food to prevent the immiscible components separating. In mayonnaise, they prevent oil and vinegar separating, in chocolate they enable it to be moulded, in bread they help it remain fresh for longer. Some emulsifiers come from natural sources, such as lecithin from eggs or wheat germ and pectin from apples or pears. Both these also carry the slightly off-putting European Union labels, E322 and E440. The more intimidating sounding name, ‘mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids’ are also emulsifiers found in nature, but are manufactured for large-scale use from plant or animal fats. They are considered safe by a US consumer interest group, as well as by national food standards bodies, though their effects on gut bacteria are currently being investigated.

Preservatives

Microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast and mould coexist with foods. Left to themselves, their actions cause food to spoil. They cause chemical reactions in food which might make it more acidic, change its colour and/or produce toxins. The aim of food preservation is to kill the microorganism or slow down its activity. A traditional method is to keep food cool, slowing down the bugs’ internal metabolism, enabling the food to last longer before it spoils. Another is to remove the water on which the bug depends, by drying or curing it with smoke or salt. Smoking seals the food, preventing the entry of bacteria, salt draws the water out of bacteria, so they are unable to function. Another method is to kill the organism, either by heating it or increasing the acidity around it. Many bacteria simply cannot survive under such conditions because the vital enzymes within them simply ‘denature’, losing their structure.

Such methods are also reflected in modern food production, with heating and sealing food in cans; by chilling or freezing and by curing meat and fish. More recently chemicals have been found that have preserving effects. These are added both to prevent spoilage and also to maintain colour and flavour for longer. Those aimed at preventing the growth of bacteria include sulphites in wine, sorbic acid in cheese and jam, benzoic acid in low sugar jams, dressings and condiments. Discolouration results from the action of enzymesthat depend on oxygen for their action; antioxidant preservatives combat this. As anyone who has treated apple slices with lemon juice knows, citric acid acts in this way. Ascorbic acid is another commonly added to cut fruit, salad mixes and fruit juices. Nitrites and nitrates and often used to preserve meat products such as bacon and salami because they not only protect the meat from micro-organisms, but also maintain the red or pink colour. Like all additives, these are subject to research and testing. Risks associated with nitrites, in particular, include a pathway in the digestive tract that can produce cancer causing agents. For this reason, levels of nitrites are strictly regulated. Scientific research suggests a number of potential harms from the addition of preservatives, but recognises their vital role in preventing dangerous infection, notably botulism.

Artificial sweeteners

The mental sensation of sweetness is the result of particular molecules in our food attaching themselves to receptor molecules embedded in our taste buds. When this happens, the receptor molecule changes shape slightly which sends a signal off via a nerve to the brain. This activates the part of the brain that creates the sensation of pleasure. The everyday table sugar sucrose is a molecule that attaches to the receptor molecule in this way giving rise to the sweetness sensation. In recent times other molecules have been discovered that also activate the protein in taste buds, some, such as sucralose, over a hundred times more strongly. Such sweeteners have no nutritional value, no calories.

For some people such as children at risk of tooth decay, artificial sweeteners may be a beneficial replacement for natural sugar – in toothpaste, for example. Over the long term, however, there is “no evidence of long-term weight loss in adults or children from using sweeteners, but a potential increased risk of type 2 diabetes” according to the World Health Organisation. It advises that “non-sugar sweeteners not be used as a means of achieving weight control or reducing the risk of noncommunicable diseases”. On the other hand, the European Food Information Council (an independent, evidence-based consumer charity) criticises the WHO report and claims that “the most appropriate studies show that using sweeteners contributes to weight and cardiometabolic benefits by reducing or displacing excess calories from sugar”. The clear lack of consensus on the scientific evidence on sweeteners is an indication of how incomplete the research base is – particularly in relation to long term effects and children. An aggravating factor is that sweeteners are not a uniform class of substances – each is a completely different molecule so each is likely to behave entirely differently, apart from its sweetening effect, when ingested in the body.

Antioxidants

Oxidation is a chemical process in which oxygen atoms are added to other atoms or molecules. Rusting is an example in which oxygen atoms in the air attach to iron atoms in a piece of metal. With food, a similar process is seen when cut fruit goes brown or butter turns rancid. In the body, it’s not so much air, as other molecules, that provide the oxygen atoms for this oxidation process. These oxidising molecules can attach oxygen atoms to DNA and to proteins, resulting in genetic mutations and destruction of enzymes. To minimise this damage, the body has natural antioxidants, which neutralise the dangerous oxidants.

Extensive research worldwide, shows that antioxidants play a vital role in promoting human health and well-being. They protect our bodies from excess oxidation, which can otherwise lead to cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and some cancers. They are also important in preserving food by slowing down oxidation processes which would alter its nutritional value as well as its flavour, colour and texture.

Antioxidants are clearly very beneficial to health and need to be welcomed in our food. Some we eat normally: vitamin C (aka ascorbic acid) for example is present in broccoli, sprouts, peppers, tomatoes and citrus fruits; vitamin E in avocado, sunflower seeds, beans and lentils; beta carotene in apricots, mangos, carrots and grapefruit; selenium in eggs, tuna, salmon, brown rice, and many vegetables. Knowing this helps explain the scientific evidence behind the familiar nutritional advice to eat plenty of fruit, vegetables and oily fish.

The Cleveland Clinic advises that a range of different antioxidants is best for health, and suggests avoiding single supplements or mythical ‘superfoods’.

A ‘rainbow’ diet of different coloured fruit and veg is widely recommended.

Colourants

Molecules that give a particular colour are sometimes added to foods to make them look more attractive or to compensate for loss of colour when they are processed and stored. Some, with names such as carotenoids, chlorophyllin and anthocyanins are naturally occurring pigments found in plants. Others like carmine from the cochineal insect, or paprika and turmeric from plants are also naturally occurring.

The presence of carotene pigment in the grass eaten by cows gives butter its yellow colour. Margerine would be a less attractive white without the carotene pigment that’s added to improve its appearance.

The first artificially manufactured pigment – a purple colour named mauveine – was synthesised in 1856. This led to an entirely new industry, originally based on processing industrial coal waste in the Ruhr region of Germany. The novelty of synthetic colour spread from textiles to the food industry, ushering in the era of artificial colourants. After early experiments with toxic additives – including arsenic, copper and lead – proved damaging, regulations were brought in by various authorities.

More recently, concerns were expressed about a link between artificial colourants and hyperactivity in children. In 2024, the UK Food Safety Agency studied six of these found in beverages and concluded that they may induce hyperactivity in some children, recommending that products containing any of them should carry warnings. Natural flavourings are increasingly sought by some consumers and producers, both to avoid any potential risk with artificial ones, but also because of possible health benefits. They tend to be, however both more expensive to produce, less stable and limited in range of colour.

Flavourings

Tim Spector, the epidemiologist who came to fame during the Covid pandemic with the Zoe app, has researched and written extensively on nutritional health. He describes the history of flavourings, from traditional herbs and spices to the recent explosion of artificial additives used to pep up bland products from the ultra-processing industry. He explains that food manufacturers are not required to specify which flavours they use – so many are in use that it would be impossible to study them all. The UK Food Standards Agency and the European Commission list those that are legal and in the USA, a Manufacturers Association (not the Food and Drug Administration), keeps a list of what it describes as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) flavourings. Spector helpfully summarises the health risks by stating that flavourings seem pretty safe overall, and they are used in very small amounts. A few that caused cancer in mice were banned. Overall he advises that it is not useful to distinguish between natural and artificial flavourings – there is so much overlap. Many flavour molecules that are found naturally in foods are also synthesised artificially, for ease of production. Examples include the pear flavour found in pears, apples and grapes; the cinnamon flavour in cinnamon and banana flavour found in many plants.

Potential harms

Chris van Tulleken’s book is unequivocal about the risks; it illustrates ways in which food producers are able to exploit loopholes in the regulatory processes of the US Food and Drug Administration to declare their own products safe. A review in the official journal of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health entitled Artificial food additives: hazardous to long-term health? pulls no punches, especially when it comes to children. It concludes that “combinations of artificial colourants, benzoate preservatives, non-caloric sweeteners, emulsifiers and their degradation derivatives have adverse effects by increasing risks of mental health disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and potential carcinogenic effects”. It specifically links artificial azo dye food colourants and sodium benzoate preservative to disturbed behaviour in children and the creation of toxic substances in animal studies. It points to associations between high emulsifier intake and cardiovascular disease and carcinogenic effects in animal studies. It links high intake of sweeteners to cardiovascular disease and depression in adults and to childhood obesity. Children are the largest consumers of ultra processed foods and “are a ticking time bomb for adult obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, mental health disorders and cancers”. It recommends banning certain dyes, setting clear limits for levels of emulsifiers and sweeteners and their cumulative effects, and requiring health warnings on food products with recommendations about healthy unprocessed foods.

Conclusion

It is clear from van Tulleken’s book, and conflicting interpretations of individual studies, that there is no clearcut answer to our concerns about the safety of food additives and processing. Nor is reassurance of a general kind really conceivable. The huge range of colourant and antioxidant molecules would all need to be studied, in varying dosages for different kinds of consumer, including babies, children and pregnant women. The effects of an almost infinite number of combinations of additives would also need to be studied. Most challenging of all is predicting effects over a lifetime. No amount of lab testing on mice for a few weeks or months will assure us about effects over an eighty-year human life.

For this reason, advice from almost all authoritative sources, focuses on minimising consumption of ultra-processed food wherever possible and choosing a balanced diet that includes a variety of vegetables, fruit, meat and fish as well as staples. The official position on additives is summarised on the website of the UK Food Safety Agency. The website Eat or Avoid provides information about a wide range of additives, including their relative safety. In the end we have to be realistic about living out lives – we are bound to eat a certain amount of undesirable additives and will want to indulge in sweet and creamy treats from time to time. For parents of young children, as van Tulleken woefully notes, compromises are sometimes essential, just to stay sane!

© Andrew Morris June 2025