What’s the point of spending billions looking for dark matter in remote galaxies? Will something so remote and abstract make any difference to our lives? Is it worth researching at such huge expense?

Thus began a group discussion about what motivates scientists. The sheer enthusiasm of the astronomer with whom the group was talking seemed almost enough to explain why we back such bizarre research. She was utterly committed to her work in a huge international project looking for this mysterious material.

The investigators were driven by the enormity of the mystery: dark matter, an invisible substance, apparently pervades all space and dwarfs what we know as ordinary matter. It might even put the whole basis of physics as we know it in question, she explained.

Astronomers are just one example of the kind of people who feel driven to find out whatever they can about things that aren’t yet understood. What is it that compels them? Why are they insatiably curious? What indeed is curiosity? As parents know all too well it’s very strong in children in their younger years. Is it a biological compulsion that keeps them asking ‘why?’ This blog looks into what science has to say about these questions.

Why are we curious?

Psychologists have carried out research that demonstrates how much we humans enjoy novelty; we have a distinct urge to seek out information and experiences that are new to us. Research on babies shows how they continually strive to learn from what’s around them; they see surprises – the unexpected – as opportunities to learn. Given the choice, they repeatedly show a preference for images and sounds that are the most stimulating: anything new is intriguing. At just four months, infants have been observed spending time playing with puzzles that have no particular function and look happy when they work out how to solve them. If the desire to explore the unknown for its own sake occurs at such an early stage in our lives, it would surely have become ‘wired-in’ through evolution, as an aspect of human make-up.

Evolution

Archaeological research suggests that curiosity was a feature of life for the earliest humans, and not restricted to children.

The elaborate design of musical instruments from 40,000 years ago suggests that curiosity played a part in their production – to try out different sounds, for example.

Figure 1 A paleolithic flute

Even older are examples of decorated handaxes, which were unusable as tools, so perhaps reflect the pleasure found in crafting them. What is it about curiosity that meant it got baked into the human genome in the time of our ancient ancestors?

For evolution to favour some trait, it has to confer an advantage that enables individuals with that trait to survive longer and produce more offspring than average. That way, the relevant genes get passed on more abundantly to successive generations. Theory suggests that it’s about the benefits of gaining information. By trying out things that you are not sure about, you stand a better chance of discovering something useful. Of course, this involves risk and doesn’t necessarily yield a positive result every time. On average, however, putting yourself in the way of new discoveries helps you build more accurate models of the world. With better understanding of how the world around you works, you have a better chance of securing food and acting safely. Knowing the tell-tale sounds of an approaching predator and distinguishing nutritious red berries from poisonous ones, are clear advantages.

Even more important for the evolution of our human species is the contribution curiosity makes to building social relationships. By understanding how to stay together and work together, bigger prizes could be bagged and the proceeds shared. Getting to understand the other members of your social group helps sustain cohesion and cooperation within the group. It pays to be nosey!

Psychology

Research in experimental psychology with human subjects today throws light on these evolved traits. Infants just a few months old tend to look away from images or sounds that they are familiar with but pay attention to novel ones. At pre-school level they are already becoming aware of the link between seeking information and being knowledgeable. They also demonstrate another important feature of curiosity – its role in reducing uncertainty. Being unsure about something you care about is uncomfortable; curiosity can help to clarify fuzzy knowledge.

Kindergarten children in the USA were tested for their ability to deal with uncertainty by measuring their response to vague images. Their ability to cope with uncertainty was linked to improvements in vocabulary and executive function (regulation of emotion and behaviour). Children taking part in imaginative situations when playing are, in effect, testing out ideas and developing their sense of curiosity.

Like children, adults also tend to prefer novelty, to seek out new information and experiences. As we grow, we move on from simply exploring what is around us, in the hope of finding new knowledge, to exploiting the knowledge we have already gained. This may account for our sense that people tend to become less curious as they age.

An interesting experiment involving visitors to the London Science Museum found that while younger people were broadly curious, older people looked at fewer topics but more deeply at each one. Curiosity remains a key feature of adult lives. We eagerly anticipate the answer to a quiz question and close our eyes and ears to the ending of stories we have yet to finish or games we have yet to watch. In other words, curiosity often leads to pleasure; we enjoy finding out. When curiosity is aroused, we find it easier to learn; and when learning is experienced as enjoyable, we are inclined to go for more of it.

Learning isn’t always enjoyable of course! Just think about those terrible times when you hadn’t a clue about the topic you were being taught; some mathematical deduction or historical event that left you blank-faced. There’s clearly a level of ‘not knowing’ that drives you to find out more, but equally there’s a level above which you just become annoyed and turn away from any idea of trying to understand. This has been researched in an effort to find the ‘sweet spot’ in which you wish to learn more. It’s obviously a vitally important factor when you try to encourage learning in others, whether as a professional teacher, parent or friend.

In a recent study, infants less than one year old were shown images of things popping out of boxes. They preferred to look at situations that were a little bit surprising but not too complex, a so-called ‘Goldilocks’ effect – not too much, not too little. Experiments with monkeys and even with AI robots have demonstrated the same effect: learning activities that are neither too easy nor too difficult are most effective. An AI-based programme in primary schools in France, which generates questions for each individual child based on what they want to learn, resulted in greater motivation and better learning. Setting your own goals motivates learning, it helps you find that balanced position between being challenged but not frustrated. The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsy captured this in his concept of the ‘zone of proximal development’ – a range between the kind of challenges a learner can tackle for themselves and ones they can’t, even with support. It’s the range within which teachers try to operate.

Neuroscience

With archaeology suggesting that curiosity evolved because it helped people survive and psychology showing how it encourages learning by giving pleasure, we look to neuroscience to understand what is happening in the brain. Is it just a matter of luck that some of us tend to be curious? Are individuals just exercising their free will when they become curious? Recent studies of chemical and electrical processes in the brain have begun to answer these questions.

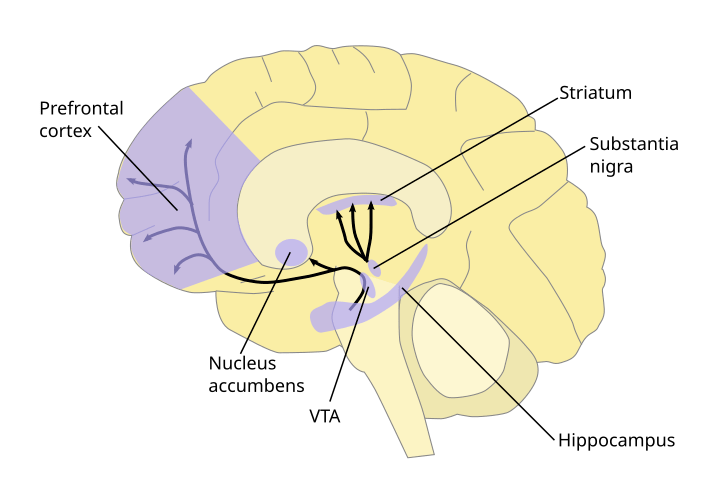

Measurement of levels of the hormone and neurotransmitter dopamine reveal that it is elevated in situations that arouse curiosity. When a stimulus is recognised in the brain as being potentially rewarding, dopamine is released (in the VTA shown in figure 2) . This is the first step in the brain’s ‘reward system’.

Figure 2 Diagram of the brain showing the dopamine pathway

The next step is the transmission of dopamine to a different area of the brain (nucleus accumbens in figure 2) where the molecules attach to receptor molecules on the brain cells (neurons) producing changes that we experience as pleasure. The same pathway activates the memory function of the brain, which will serve as a reminder that this particular experience was pleasurable – and worth repeating. At the same time, a signal is sent by a different pathway to the pre-frontal cortex, an area behind the forehead associated with planning and regulation of behaviour. This enables the brain to evaluate the experience and consider whether to repeat it in future. This can lead on to reinforcement of beneficial experiences and subsequent learning. This explanation seems to bear out the adage, well-known to performers and sports people: “practice makes perfect”. The importance of the memory aspect was demonstrated in an experiment in which volunteers were placed in an MRI machine and asked a series of trivial questions and had to wait 14 seconds before hearing the answers. They were better able to remember those answers for questions about which they were curious, and MRI scans showed that the area of the brain where memories are created was activated.

Curiosity and mental health

A 2025 study of 17,000 people in China looked at the relationship between childhood curiosity and depression in adulthood. It found the risk of depression was reduced in adulthood for people who had been curious in childhood, because it helps foster psychological and cognitive flexibility when facing complex situations. Childhood curiosity is linked to feelings of belonging and the ability to establish social connections with others, known factors in preventing depression. It also encourages positive beliefs, such as optimism, in children, which go on in adulthood to act as a protective buffer against mental health problems. A psychotherapist writing in the journal Psychology Today offers advice to help adults maintain their curiosity:

- try engaging in things you enjoyed in the past

- do something unexpected.

- ask questions – they may help deepen connections between things

- explore new places

A contrasting problem can arise when curiosity is unbridled. As we have seen above, curiosity is a vital trigger for learning, especially in our younger years, and leads to healthy development. It stimulates us to explore new ideas and seek out new experiences. In some situations, however, this can go too far and cause mental distress. Curiosity about a health issue, for example, may lead into fear of the unknown or of future harm; curiosity about the nature of existence or meaning of life can lead to overwhelming anxiety. In obsessive-compulsive disorder, the anxiety aroused through excessive curiosity can lead individuals to exaggerate dangers or imagine worst case scenarios after a trivial incident (‘catastrophise’) and seek reassurance to reduce the uncertainty or to control their thoughts through compulsive behaviours. Advice about dealing with this condition emphasises developing an awareness of one’s thoughts and feelings without judgment (being ‘mindful’) and encouraging acceptance of uncertainty. This helps reduce the impulse to engage in compulsive behaviour. By confronting fears gradually individuals may be able to desensitize themselves to the anxiety associated with their curiosities, thus reducing the compulsion to seek excessive reassurance.

Other species

Of course, it’s not only humans that need to explore their surroundings to get an accurate picture of risks and opportunities. It’s no surprise that many species also demonstrate curiosity – though it’s a less well-defined concept outside the human species.

The list, according to ‘Faunafacts’, includes the African Grey Parrot which has its work cut out finding its way into pistachio nuts; ants, with their intense sense of smell and highly developed social instincts and chimpanzees, who love playing and exploring their surroundings. Crows enjoy toying with different objects and figuring out how to solve problems, while dolphins not only play and explore readily, but also remember where they have been and what they’ve seen. Cats are notoriously curious and exhibit intelligence, as their owners know well; dogs too are curious, especially in relation to food. Octopuses are particularly intelligent and have been observed lifting the lids off boxes and jars to get at food. Elephants, otters, squirrels, pigeons ..… the list is long. It’s clear, from simply watching these animals going about their business, that curiosity must play a central part in their search for food and homely accommodation.

Conclusion

If you’ve managed to read this far, you must be curious yourself! It’s reassuring to know that scientific research reinforces much of what we know from everyday experience. Curiosity is a wonderful instinct that leads on to love of learning and greater understanding of the world into which we are born. Cultivating it is a key part of what we try to do as parents, teachers and citizens. Long may curiosity thrive – it never did kill the cat.