“Ultra Processed People – it’s a new book by Chris van Tulleken, the TV doctor twin” explained Sarah to her science group. “Let’s all read it and talk about the science behind it” she suggested. What followed was a powerful discussion about what gets added to the food we eat and why the food industry does it. This blog is inspired by that discussion.

Van Tulleken’s underlying message is simple: he compares food processing to an arms race: a never-ending battle between basic human impulses and profitability in the food industry. Blaming individuals for poor eating habits and excess weight misses the point: all of us are caught up in a complex social and economic struggle with a system that continually outsmarts us. He explains that healthy eating is not just a matter of picking on single ingredients like sugar or fat, but about understanding food as a whole, including what is done to it before it reaches us and what drives us to eat it. He expands the concept of ‘processing’ beyond machine processes and chemicals added in the factory, to the marketing efforts made to entice you into buying it.

The onslaught of the processing industry arrived a little later in Brazil than in many other countries. This enabled its impact on the subsequent obesity epidemic there to be tracked from the very beginning. A key research centre there offers a simple classification of the levels of processing:

- found in nature – veg, fruit, meat and fish, for example.

- processed ingredients – such as oils and honey

- processed for preservation – like smoked meat, canned fish and fresh bread.

- ultra-processed – industrial food, in which whole foods are broken down, then chemically modified

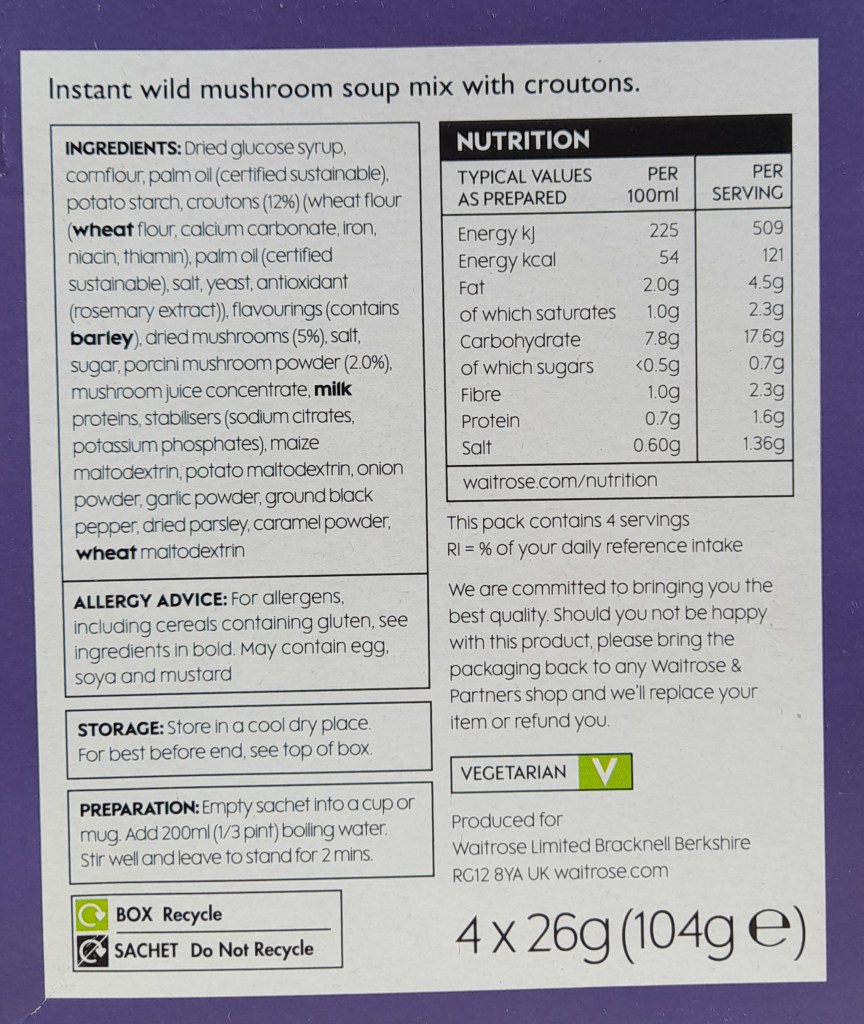

As there is no exact definition of the phrase ‘ultra-processed’, he offed a simple rule of thumb: if the list of ingredients includes items you wouldn’t normally stock in your kitchen cupboard, its ultra-processed.

For Chris van Tulleken, this wider context for the rise in obesity was driven home when his twin (with identical genes to himself) started putting on weight and losing form when he was under sustained stress in his personal and professional life. Reflecting later on his efforts to cajole his brother to change his habits, Chris came to realise that he’d been aggravating the problem, rather than helping, by adding guilt to his brother’s stress. Our emotional state plays a part in the arms race, as well as the chemistry of the ingredients we ingest.

Ultra-processed food and obesity

The Brazilian scientist Carlos Monteiro hypothesised that it was rising consumption of the fourth category, ultra-processed food (UPF) that lay behind the rapid growth in obesity in Brazil. To test this he conducted a trial, putting one group of people on a UPF diet and another similar group on a normal diet, both with the same number of calories. As he had surmised, the UPF group put on weight, the other didn’t.

Understanding the effects of individual ingredients, like the sugar and fat listed on food labels, doesn’t give a complete picture of unhealthy eating. Individual ingredients may behave differently when isolated in a laboratory test than when combined in a processed food.

The processing method also matters. A clear example is fruit juice. When put through a blender the very cells of the fruit break open, releasing their sugar contents in a sudden rush. Your insulin-controlled absorption process is overwhelmed, causing the system as whole to convert the excess sugar to fat. If the same fruit were simply to be eaten whole or crushed, on the other hand, the cells would remain intact, fibre would be retained and the absorption process would proceed at a manageable pace, without adding fat.

Physical processes, such as blending, crushing, heating and centrifuging, break up foods and alter the balance of nutrients that get absorbed and fibre that slows the pace of absorption. Chemical processing plays an additional, potentially more worrying role. Substances that add flavour, stabilise immiscible ingredients, enhance texture or extend shelf life are routinely added. Van Tulleken sees the manufacturing of ultra-processed foods as a consequence of market-driven economics pushing companies to minimise costs in order to remain competitive against their rivals. Substituting cheaper, often synthetic, ingredients for the more expensive naturally occurring ones, is one way of doing this. Persuasive marketing, to appeal directly to our prehistoric urge for energy-rich fats and sugars, is another.

Sarah recalled Chris van Tulleken’s description of the marketing strategy for Cola which emphasises the health benefits of exercise, even though research shows that, in relation to obesity, this factor is minor compared to healthy eating. “And then there’s gooey food” added Sarah “it goes down so easily”. She recalled van Tulleken’s concern that the body can’t respond to it fast enough, so the usual feeling of satiety isn’t properly triggered, and we eat more, adding to the producer’s sales. “Children’s jaw bones are failing to develop properly through lack of chewing” she added.

Pringles was another food product highlighted in the book. Their characteristic shape fits snugly over the tongue in such a way that it activates more taste buds than usual. As Julie pointed out, this, together with their appealing crunchiness, makes them very tempting in the short term but, she added, “they quickly turn to mush, after that”. “And they put an artificial smell into crisp packets to give an instant aroma as soon as they are opened”.

Amazed at all the examples of industrial interventions, Marian checked: “are there really engineers working in the food industry to design all these aspects – the smell, the texture, the crispness – of food products?” With an air of resigned realism Julie commented that “the companies are just trying to make money, not feed people”. “And these are the qualities that customers demand” added Sarah.

International comparisons show a positive association between availability of ultra processed foods and levels of obesity in the population. In Portugal and Italy UPFs contributed less than 15% of the dietary calories, whereas in Germany and the UK, the figure was closer to 50%. So what is it that lies behind our compulsion to eat unhealthy food products? What do neuroscience and psychology tell us about our perverse desires? And what do the sciences of taste, texture and sound tell us about our passion for gooeyness and crispness?

Sweet and fat

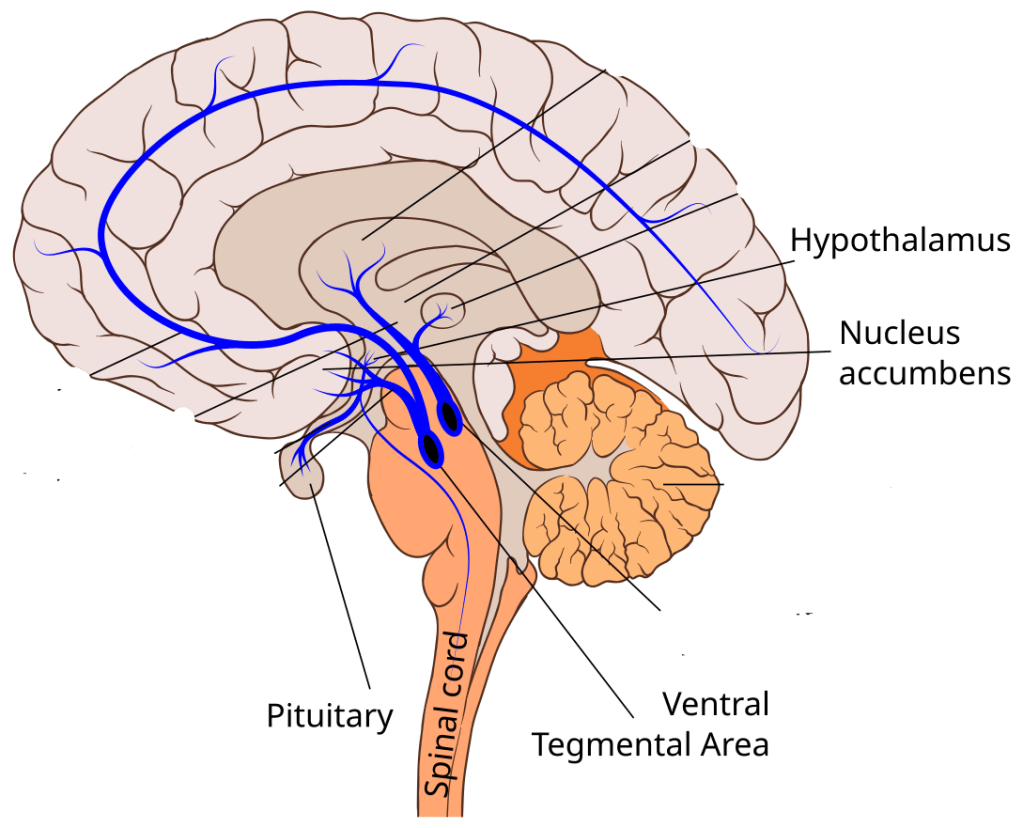

At the technical level, sweet tastes are picked up on the tongue, then signalled to the brain through nerves. There the reward system is activated to make us feel good about the experience so that we go out of our way to look for more.

Messenger molecules such as dopamine are released, creating the sensation of pleasure. Memory circuits are engaged to ensure we remember exactly where we found those berries or that honey.

An explanation of this system is given in blog 2.30 Resisting Temptation

These mechanisms evolved in early humans to motivate our ancestors to capture the bountiful energy locked up in sugar molecules. Early humans weren’t troubled by excess sugar – quite the opposite. Today, with sugar all round, especially in processed food products, the dangers are all too apparent. In excess, it overloads our control system, causing the surplus molecules to be converted into fats, which get stored in inappropriate places around the liver, muscles, pancreas and other organs.

Molecules of fat are also loaded with large quantities of energy, as a quick look at the calorie table on a food label will tell you. Our bodies have also evolved to respond enthusiastically to these, partly through flavour and partly texture. Over evolutionary time, the elements of our complicated system of reward have become encoded in our DNA – we are genetically disposed to crave sweet and fatty foods, inappropriate as this may be to modern conditions.

Texture and processing

Apart from the nature of the ingredients and their nutritional values, other factors are at play in our body’s response to food. As a 2022 review of research puts it, “the nutritional facts on labels … do not truly reflect what is absorbed as energy and the true metabolic impact of a food”. A key factor that doesn’t appear on food labels is texture. For example, the acts of grinding, crushing or heating – whether in the mouth or the factory – can break down food structure, exposing the ingredients more directly to enzymes, which then act more quickly to release sugar and other components.

The solidity of food also affects digestion: liquids are eaten more rapidly than solids and, for the same number of calories, make you feel less full. By choosing semi-solid versions of a chocolate drink, custard or rice pudding, for example, average food intake is reduced by up to a third compared to a liquid version. Eating harder foods involves smaller bite sizes and longer chewing time. This slower process signals to the brain that food is on the way, reducing the amount of food you eat before feeling full. Conversely, adding butter and other spreads helps lubricate food, speeding up the eating rate as well as adding calories.

Conclusion

The drift of van Tulleken’s book shook people in the discussion group and affected their attitude to food choices. They are thinking about how best to change their buying and cooking habits to emphasis unprocessed or minimally processed ingredients. If you can read the tiny print, food labels help you identify and avoid obviously ultra processed foods. But, with so many routine ingredients containing additives, it’s almost impossible to avoid them entirely. Van Tulleken proposes that food labelling should be simplified and upgraded to emphasise potential risks to health. For us consumers, the best advice is to eat a broad and balanced “rainbow” diet, rich in unprocessed veg, fruit, meat and fish.

Working out what the unfamiliar words on food labels actually mean and what risks they pose is a challenge. Carry on reading Part II of this blog if you would like to find out more about the unfamiliar words you read on food labels – stabilisers, emulsifiers, preservatives, sweeteners, antioxidants, colourants and flavourings. Nutritional advice on the good and bad aspects is also summarised. I hope you find it helpful.

Read more: Ultra Processed Food Part II Additives

Andrew Morris June 2025