It all began with the future of the NHS. A science group was discussing the idea that we need to invest in preventing disease in its early stages rather than wait for it to became manifest when we get older. A community facility in every town, diagnosing and giving advice, would reduce the need for expensive hospital treatments later, according to expert Sir John Bell.

“A good idea in principle” thought Julie, “but will people act on advice, if it runs against their basic desires?” The concept was that community health centres, as local as the vaccination centres during the pandemic, would take blood and other samples, to look for ‘biomarkers’ – indicators of health risk. Technicians, using the most up-to-date technology would predominate and counsellors would provide help for people to develop healthier dietary and exercise habits. The 35 minute talk is here on Youtube.

What exactly do we mean by biomarkers? Are they just blood tests?” Mary asked. She was aware of things like smart watches, and had read that they are OK for some things like heart rate and oxygen saturation, but wildly inaccurate for other things. “Perhaps a divide is going to develop as technology enables some people to monitor their health, but not others” added Julie.

Biomarkers

The World Health Organisation defines a biomarker as “any substance, structure, or process that can be measured in the body or its products and influence or predict the incidence of outcome or disease”. In practical terms it’s usually an indicator picked up through a fluid or tissue sample. An unexpected protein picked up in the blood or urine is one kind of biomarker. PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen) is an example, found in the blood; it’s associated with an enlarged prostate, which may indicate cancer. A gene that has mutated is another kind of biomarker. One type of breast cancer is caused when a gene known as HER2-gene mutates, leading to overproduction of a growth-promoting protein called HER2. The gene, or the protein for which it codes, are both biomarkers. By detecting and measuring biomarkers such as these, clinicians are able to diagnose conditions, predict outcomes and select the most suitable kind of treatment.

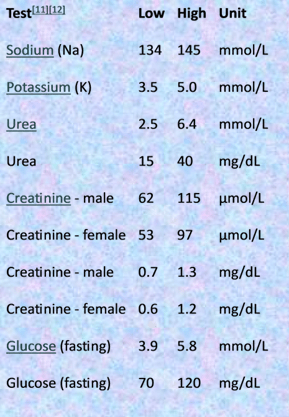

A different kind of biomarker, familiar from the results of routine blood tests, measures the level of various substances derived from the food we eat. The sugar, glucose is one example, the fats known as triglycerides are another. Others measure the functioning of specific parts of the body. Levels of a waste product called creatine indicate whether the kidneys are functioning properly in their task of removing the substance from blood; levels of potassium and sodium provide information about the hydration of cells and functioning of the nervous system.

Figure 1 A typical bood test list

Yet another type of biomarker is the antigen produced by bugs that cause infection. Typical antigens are the proteins on the surface of viruses. The antigen test used to check for Covid infection picks up this particular type of biomarker – the so-called ‘spike protein’. A related kind of biomarker is the antibodies that the immune system may produce when the body is threatened by pathogens or tumour growth. Each variety of antibody is specific to one particular type of pathogen. Detecting the presence of antibodies in blood and identifying the specific bug or abnormality to which they correspond, can indicate conditions that are otherwise silent.

This small sample, from the huge range of biomarkers available, provides a glimpse of the potential of systematic testing. Malfunction and disease conditions can be detected and treated long before any symptoms are apparent. Extending diagnosis of this kind to people throughout the stages of life would be one of the key functions of a more extensive network of community-based health centres.

Technicians in place of doctors

Transferring resources from hospitals, that treat indivduals when they are sick, to community health centres that screen large numbers of people earlier in life, is one of the proposals for radical restructuring of health services.

Figure 2 Community health centre, Solomon islands

The economics depends on staffing such centres largely with technicians skilled in administering diagnostic tests, rather than more highly trained and costly doctors. “It’s an interesting idea” said Julie at this point in the discussion “but, what would technicians actually be able to do? Isn’t there a risk they would make less well-informed referrals, wasting time and money?”

Often overlooked are the many roles played by trained medical staff other than doctors and nurses. On the technical side there are the radiologists who operate MRI, PET and CT scanning machines; phlebotomists who take blood samples, pharmacists who deliver medicines and pathology technicians who process blood and biopsy samples. On the health promotion side, there are dieticians, physiotherapists and occupational therapists who help reduce the incidence of illness and injury or speed up recovery. Taking the opportunities presented by the growing range of biomarkers obtained from body fluids, biopsies and scans, will surely call for greater numbers of such experts. The expectation is, that by distributed these widely in community facilities across towns and cities, their early diagnostic and preventative work would reduce the burden on doctors and nurses treating sickness in hospitals.

Looking after your own health

At this point, discussion turned to the efforts we can take as individuals to take more care of our own health. Julie mentioned a friend who was overweight and had lost three stone (about nineteen kilos) using the new weight-loss medication Ozempic. She subsequently managed to sustain this by controlling her diet, using the 5/2 method (five days normal and two days fasting). Marian thought this believable; “after all”, she said “I quit smoking decades ago and can honestly say I no longer struggle”. On the other hand, it is often reported that diets don’t work in the long run – you eventually give up and put the weight back again. So, what is going on with our ability to resist temptation over the longer term? Is it just a matter of personal willpower or are there methods for bolstering your resistance?

Temptation

Figure 3 Eve tempted by the snake – William Blake

Research in psychology has led to a model of the pleasure-seeking process, divided into three phases:

- Wanting – like waking up with the idea of getting some coffee

- Liking – like actually smelling the coffee

- Conscious pleasure – like enjoying drinking coffee.

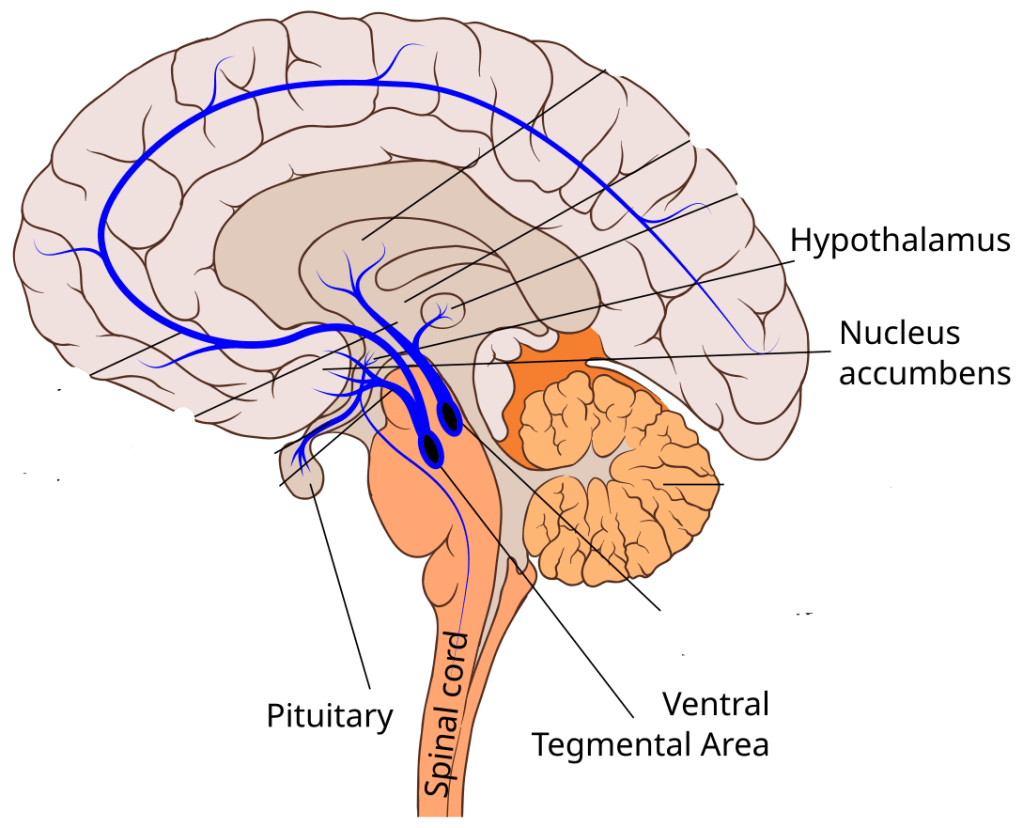

Learning is also important – the ability to remember the pleasure, so you are repeat it when the opportunity arises. The biological purpose of this kind of desire is, of course, to motivate us (or, more accurately, our distant forebears) to take favourable actions, like stocking up on sweet, energy-rich berries when you get the chance. The system in our brains that coordinates pleasure-seeking behaviour is much the same whatever the source of pleasure: eating, drinking, gambling, having sex or taking psychodelic drugs. This system involves a set of interconnected areas of the brain, known as the ‘dopamine pathway’. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter, a chemical that connects one nerve cell to the next. It is particularly associated with rewards and pleasure. When you perceive something that is potentially rewarding, like appetising food, extra dopamine gets released. To make this happen, signals from the external world about potentially rewarding things get picked up by our senses – the eyes, nose, ears and skin – and sent to various parts of the brain for processing. From here nerve messages are sent on to a place where dopamine gets released – a group of nerve cells known as the VTA (Ventral Tegmental Area) – see figure 4.

A number of pathways, shown in blue in the figure, lead off from this area to different parts of the brain. When dopamine molecules travel along the lower one of these pathways, to an area known as the nucleus accumbens, it triggers feelings of pleasure in the nearby amygdala, an area associated with emotion.

Figure 4 The dopamine pathway

This flow of dopamine that creates a pleasure sensation also activates a different area of the brain, associated with decision-making and planning – the prefrontal cortex (via the long blue line in figure 4) – and other areas that are responsible for storing memory and controlling behaviour. Neurons in these areas are able to link the pleasure response to the original stimulus – the sight or smell of food, for example. By committing this association to memory, the brain is able to encourage behaviour likely to repeat the rewarding experience. This is how we build up habits.

Certain mood-altering drugs can directly cause excessive amounts of dopamine to be released, without needing a signal from the senses. This causes a heighened sensation of pleasure which also lasts longer than usual. These effects are studied in the laboratory using rats, who soon learn to keep pushing a lever that delivers cocaine. Unfortunately, excess dopamine also reduces levels of serotonin, a different neurotransmitter, associated with happiness. Over time the body requires higher levels of dopamine just to maintain its reward system, so serotonin levels fall, leading to lower mood – a sad consequence of repeated use of addictive drugs.

There’s more on how thoughts in the brain link to actions in the rest of the body in the Read More section below.

Resisting temptation

So much for the pleasure-seeking systems in the brain; what about the complementary part that resists temptation? How does that work? It’s long been noticed that people who have suffered injury to the front of the brain – especially the right hand side – are less able to resist their immediate desires. Studies using MRI scans of the brain have reinforced the idea that the right-hand side of the prefrontal cortex (behind the forehead) is involved in inhibiting pleasure-seeking impulses. In an experiment at Montreal university a group of males was exposed to erotic imagery and invited first, to respond freely, then subsequently to make efforts to inhibit their response, to feel detached from the stimulus material. While trying to inhibit their feelings, the right hand side of the prefrontal cortex was active and the areas associated with emotional processing (amygdala) and hormone secretion (hypothalamus) were not. It seems that the neural network that links the two distinct brain systems – one for arousal and one for inhibition – is an esential part of how we self-regulate our emotional responses. As the Canadian researchers point out this “suggests that humans have the capacity to influence the electrochemical dynamics of their brains, by voluntarily changing the nature of the mind processes unfolding in the psychological space”. This idea of a balanced system is reinforced by other experiments that temporarily disrupt areas of the brain magnetically through the skull. People offered a high-risk or low-risk gamble in a game tended to choose the higher risk option when the pre-frontal cortex was disrupted. This region clearly exerts top-down control, modulating self-interest when we make decisions. This capacity has presumably evolved as an essential part of human functioning, without which we would, in the words of the researchers, “be slaves of our emotional impulses, temptations, and desires and thus unable to behave socially adequately”.

The psychology

While neuroscientists are studying what is happening in the brain when we resist temptation, psychologists are doing experiments to investigate how we behave in such circumstances. In games that encourage us to override the temptation of an immediate reward (such as money or cake) in order to gain a larger one later, children and adolescents generally do less well. This is thought to be because the prefrontal cortex matures later than other parts of the brain, making control of immediate impulses more difficult for youngsters. Another factor that makes people of all ages less able to resist temptation is stress. When people are exposed to loud noises or frustrating tasks before being asked to resist a temptation, their capacity for self-control is reduced. And if one frustrating task is followed by another, your capacity to resist temptation wanes further, rather like a muscle tiring with use. Controlling your temptation in one moment (to scream at your annoying boss, for example) can lead to more impulsive behaviour in the supermarket afterwards.

On a more philosophical note, our ability to resist temptation raises the long-standing question of free will. Is there such a thing as ‘willpower’, helping us override our impulses? Some research in neuroscience suggests that the actions we decide to take have already been pre-figured in the networks of the brain, fractionally before we become consciously aware of them. The suggestion is that free will is an illusion, born of those occasions in which an automatic impulse just happens to correspond to a conscious thought. On the other hand, it’s difficult to explain how human beings would have developed the complexities of their behaviour and created functioning societies if the individual had no conscious control over their actions. So, ‘free will’ remains a debating point amongst researchers as well as the general public.

One suggestion about why humans have free will, while other species appear not to have, comes from evolutionary thinking. Perhaps it evolved in early humans because in enabled increasingly complex social groups to evolve, which in turn led to more advanced ways of prospering, through cooperation and tool making. Powering the brain to make decisions voluntarily, however, requires very large amounts of energy. Brain cells consume energy, just as muscles do; they use up 25% of the body’s total supply. For this reason the ability to resist temptation needs to be used sparingly; as many actions as possible need to be automatic or ‘instinctive’ as these consume much less energy. This theory explains why our reserves of apparent ‘willpower’ can be so easily exhausted. Resist that doughnut, get to the gym, but don’t overdo it – you may just find yourself taking it out later on some poor innocent!

Conclusion

The discussion that inspired this blog began with consideration of how modern health services need to be transformed. The emphasis would shift from treating the elderly after they have become sick, to helping people earlier in life to avoid unhealthy life-styles. The economic logic of this is compelling, as research throws up more and more useful biomarkers, and diagnostic testing becomes ever more sophisticated. Psychologically, however, adopting healthier lifestyles depends critically on our ability to regulate our more instinctive tendencies, especially in relation to food, alcohol, narcotics, tobacco and taking exercise. Thanks to modern imaging research on the brain and experiments in psychology on patterns of behaviour, we now know something about how our bodies deal with temptation. This will surely help health promotion services develop in a way that is realistic for most people. As an individual it’s clearly a good idea to make efforts to live healthily, but willpower tires easily; let’s not overtax it in the process!

© Andrew Morris 13th March 2025

Read more

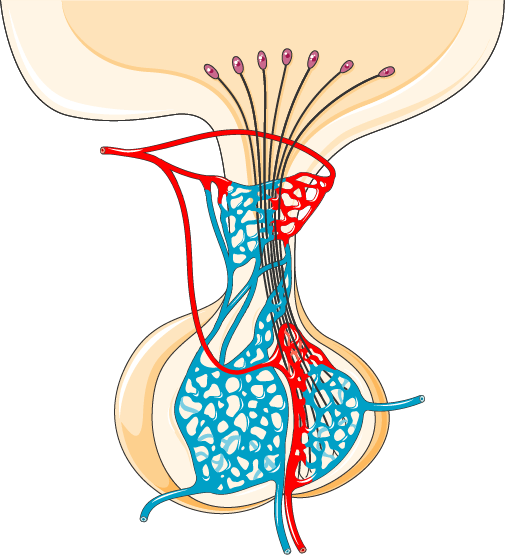

As Patrick pointed out in the discussion, however much we learn about pathways and mechanisms in the brain, it remains diffcult to understand how electrical impulses between nerve cells in the brain can lead to the subjective feelings we experience when exposed to desirable things, like food, drink, sex and gambling. To gain some insight into this, one important bodily system proves helpful. Called the HPA (Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal) axis, this system connects impulses in our brains to actions in the rest of our body.

HPA axis

The HPA system connects a part of the brain (hypothalamus) to important glands. The first is the pituitary gland which is about the size of a kidney bean, and located at the base of the brain, close to the hypothalamus. It is the point at which the brain meets the rest of the body.

Electrical signals pass along nerves from the hypothalmus into the pituitary gland . These nerves are shown as black lines in figure 5. Here they cause key hormones to be made and secreted into the bloodstream (red arteries, blue veins).

Figure 5 The pituitary gland

Once in the bloodstream, these hormones travel to other glands where they stimulate the production of further hormones which help to regulate a huge variety of functions. These include: energy management, growth, sexual function, blood pressure, metabolism, temperature, pain relief and many aspects of childbirth, pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Given this physical point of connection between brain activity and hormone production, we can begin to imagine how thoughts and perceptions buzzing around in the brain can give rise to sensations in the rest of the body. To give an illustrative example, the hormone oxytocin is produced in the hypothalmus, in the brain, then passes on to the pituitary where it is released into the bloodstream. When the hormone reaches its target organs it gives rise, when appropriate, to various prosocial feelings and actions involved in bonding, loving, reproduction – ultimately in childbirth.

Other hormones produced at the far end of the HPA axis – the adrenal glands – go on to play key roles in regulating the metabolism of fats, proteins and sugars, blood pressure, sexual functioning, and the flight-or-fight response of adrenaline, amongst many other functions – an amazing range of functions being mediated though this one axis. An action in the brain causing a plethora of physical actions in multiple parts of the body.