Viagra was discovered by accident, Jean recalled during a group discussion. Apparently, a nurse had noticed an unexpected side effect for male patients taking a drug designed to increase blood flow to the heart.

“What about Ozempic?” Jean asked, referring to a popular new drug aimed at helping people lose weight. “Was that discovered by accident – or was it by design?” “Does Ozempic interfere with your hormones?” asked Helen, “after all you can get very hungry before a period”. “Yes, and women can get strange cravings during pregnancy” added Patrick.

The group recalled a visit to an endocrinologist at St Bartholomew’s hospital in London, in which they had learned about specific hormones that link activity in the gut with feelings of hunger and satiety brought on in the brain.

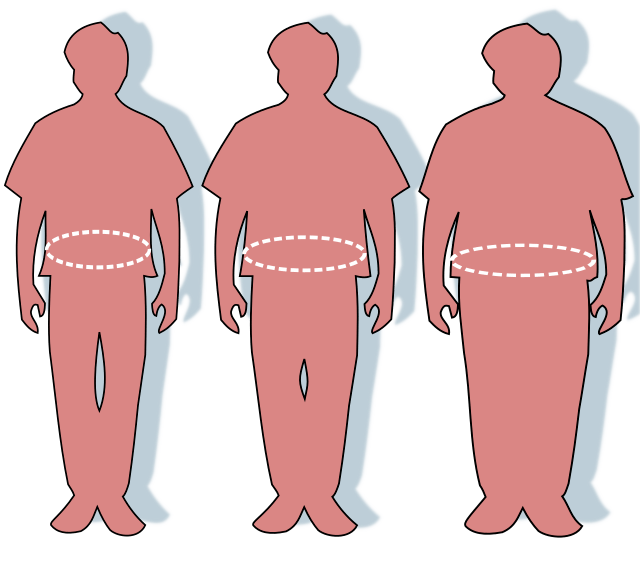

The search for a weight loss drug

The clue to finding a weight control drug lay in understanding the action of these hormones. One, called ghrelin stimulates pathways in the brain that drive us to eat. It also increases the production of insulin, needed by the body to absorb the sugar (glucose) that food delivers to the bloodstream. Ghrelin is produced in an empty stomach. A second hormone, leptin, has the opposite effect: it signals satiety to the brain, the feeling of fullness. Leptin is produced in fat cells, and signals to the brain the level of the energy stored in these cells. When energy levels are high it causes a lowering of appetite; when levels are low it stimulates feelings of hunger. A third hormone with the catchy name GLP-1 also plays a part in the delicate task of maintaining a healthy energy balance: eating when energy reserves are low and ceasing when the storage cells are full.

By imitating GLP-1, the active ingredient in Ozempic, called semaglutide, enhances these weight-reducing effects.

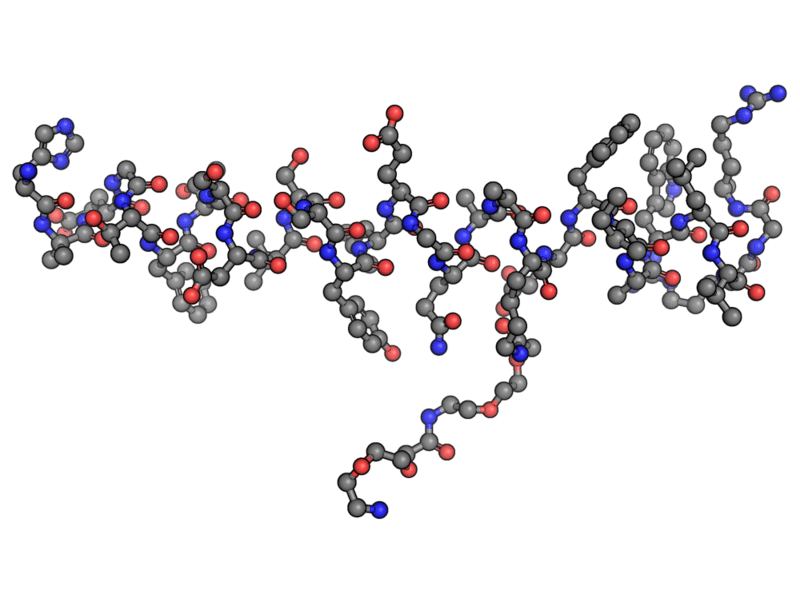

Figure 1 the semaglutide molecule – aka ozempic

As a result, glucose levels in the bloodstream fall, reducing the negative effects of diabetes and obesity. High blood sugar levels are a risk to many parts of the body because they lead to damage to blood vessels. These become less elastic and narrower, thereby reducing the supply of blood and oxygen to the heart, eyes, nerves and other organs. Research has shown that Semaglutide helps with losing weight and also reduces the risk of heart problems and other issues associated with diabetes.

Rational drug design

The hunt for effective drugs has come on in leaps and bounds over recent decades. Once, inspired guess work and countless speculative trials were needed to strike lucky on an effective molecule; today intelligent design is a real possibility. It’s because we now know a lot more about how specific molecules interact with the body. Research is providing detailed information about the precise structure and activity of large molecules in the body. Such molecules, especially proteins, play essential roles in the chemistry behind our bodily functions. Processes that we take for granted, like digesting food, activating nerves and moving muscles, often depend on the activation of large protein molecules, by much smaller ones, such as hormones and neurotransmitters. Small molecules are able to turn on pathways in the body or switch them off. This happens continuously all over the body, to maintain the balance needed for life – the right energy level, right temperature, blood pressure, oxygen level, and so on.

Illness and pain are often caused by a malfunction in one of these pathways, and effective medicines may rectify this. In the past, the development of new medicines, relied heavily on inspired guesswork and sometimes on traditional botanical remedies. Today medicinal chemists try to understand more precisely which large molecules are active in a pathway and which small molecules activate them. Knowledge of the structure and electrical properties of these molecules is building up through techniques such as X-ray crystallography, enabling far better guesses to be made about what kinds of external molecule might make an effective medicine.

A good example is the case of aspirin. Historically, the active ingredient, known as salicylic acid, was extracted by an Italian chemist in the 1830s from the bark of the willow tree. Fifty years later, this substance was synthesised by the emerging German chemical industry from a by-product in the manufacture of dyes from coal tar. A modified version – acetylsalicylic acid, now known commercially as aspirin – was invented by a chemist who had watched his father suffering from vomiting side-effects of the original form. It worked – but it was another seventy years before a British pharmacologist worked out how: aspirin blocks an enzyme that produces the substance known as prostaglandin that causes inflammation, swelling and pain.

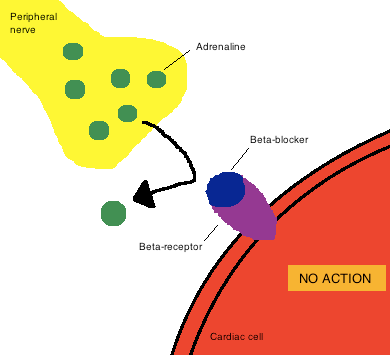

An example of another well-known medicine is a beta-blocker, a medicine that helps regulate the heart, mainly by slowing it down. It is used for a wide range of heart conditions, including heart attacks, high blood pressure and angina.

The heart is stimulated by the flow of adrenaline from nerve cells into the muscle cells of the heart. In figure 2 molecules of adrenaline (green) are released from nerve cells (yellow) and get picked up normally by receptor molecules (purple, known as beta receptors) on cells of the heart tissue (red).

Figure 2 action of beta blockers

As their name suggests, beta blockers (blue) are molecules with the right shape and electrical nature to occupy the place on the receptor that normally receives the adrenaline molecules. In this way it blocks adrenaline, reducing the amount reaching the heart, hence slowing it down.

The challenges of drug development

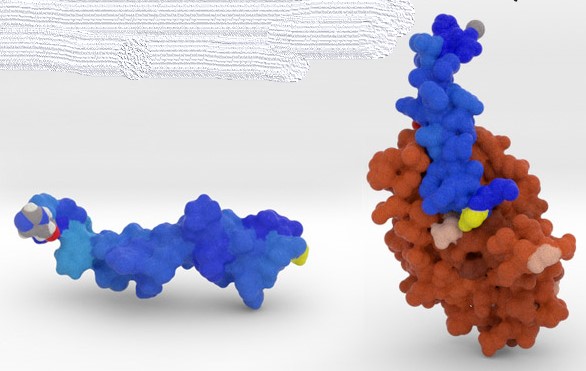

The new world of rational drug design m⁹eans that molecules can be prepared in the lab that are intended to fit precisely into a given site on a receptor molecule in the body.An example is the Ozempic drug that triggered off this discussion.

It mimics a natural molecule in our bodies, called GLP-1, that helps regulate appetite (blue in figure 3). This molecule fits precisely into a site on the receptor molecule in your body (brown), and activates it to reduce glucose levels in the blood. Ozempic just imitates this, thereby enhancing the natural effect.

Figure 3 GLP-1 molecule (blue) and its receptor (brown)

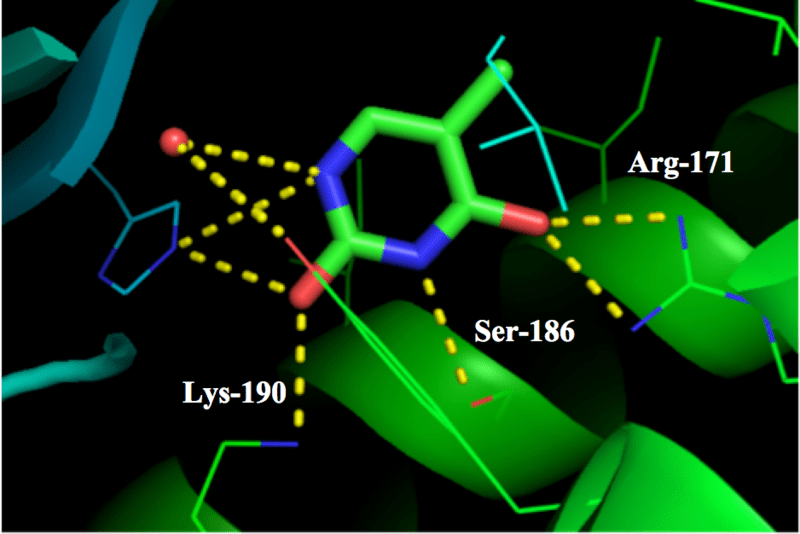

But designing a drug to “fit” is no mean task. It has to fit in the geometrical sense – its atoms must fit into a cavity or ‘binding site’ – but it must also fit electrically. Many atoms are slightly charged – either negatively or positively – so, positives on a drug molecule must sit close to negatives on the receptor molecule to which it is going to attach (and vice versa).

Figure 4 shows in detail an example of this. The small molecule known as thymine is shown as a hexagonal ring of atoms (red = oxygen, blue = nitrogen) with three branches sticking out. This small molecule interacts with parts of the big receptor molecule (thinner lines and green ribbons) through a number of weak electrical attractions, shown as dotted yellow lines.

Figure 4 Small molecule interacting with a big receptor molecule

The small molecules we have in our bodies have evolved, physically and electrically, to fit in this way. Not only do they have to fit, but they also have to activate the receptor. This means they either click that receptor molecule into a new position, like a switch, or block the site so no other molecule can get in to activate it (like a beta blocker). When a small molecule like a drug or hormone clicks a receptor into a new shape it enables the receptor to take some kind of chemical action: cutting some other molecule in two, for example, or splicing together two bits to make a new molecule.

That’s the way drugs work, once they are at the right place in the body to carry out their healing action. Getting there however is another challenge that drug designers have to meet. This means that a potential new drug, however well it does its job at the active site, has to pass through the digestive system unharmed (if it is a pill). It has to survive the acid in the stomach and then get absorbed through the lining of the gut to enter the blood stream. Once there, it has to survive long enough to reach the cells that it is intended for and then be able to penetrate the membrane surrounding the cell. There are many ways it can fail on this journey.

Once a molecule has been found that manages to make it to the active site – usually after many unsuccessful candidates have been tried – and is successful in performing its task, the potential new drug has to pass a number of further tests. Is it toxic in any way? Does it affect other cells than the intended ones – what we experience as ’side effects’? Does it, for example irritate the stomach lining, or raise blood pressure? As pharmacological knowledge progresses, it’s becoming clear that many small molecules do indeed have multiple effects on different kinds of cells, often in distinct organs. The action of aspirin described above, for example, has the beneficial effects of reducing both pain signals via the nervous system and the likelihood of thromboses (blood clots) forming in veins and arteries, because it blocks the production of prostaglandin hormones. On the other hand, the same prostaglandin molecules also play a positive role elsewhere, protecting the lining of the stomach and intestines. Thus, by blocking prostaglandin production, aspirin can also have a negative impact in the gut. It’s for this reason that the pros and cons of any potential drug have to weighed up and dosages worked out carefully before permission is granted for their use,

Conclusion

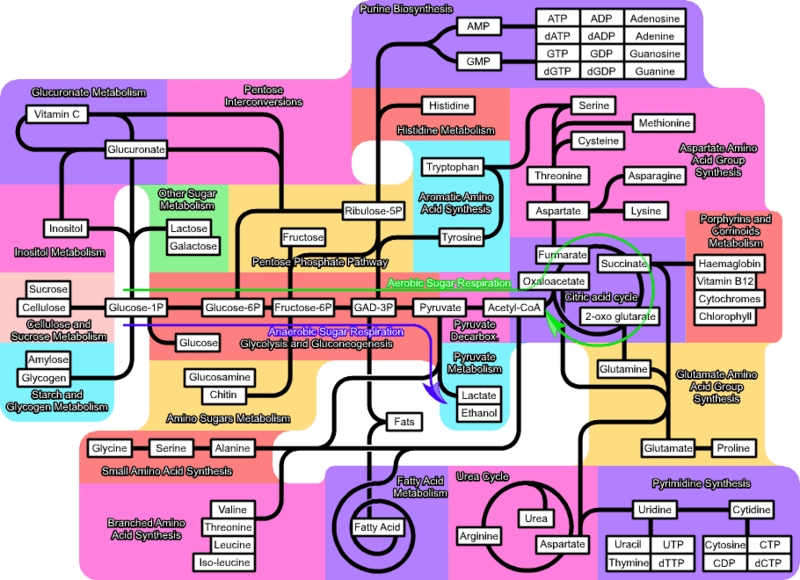

The topical question about the new weight-loss drug that launched this story has led on to the wider question of how small molecules in general – drugs, hormones, neurotransmitters or any other kind – have their effects on our bodies. There are endless variations of the precise mechanism by which such small molecules interact with our bodies, but there are some broad principles. Small molecules bind to large molecules such as proteins, DNA and RNA, in our bodies which act as receptors for them. Once bound, they may activate or inhibit the larger molecules, causing the latter to either function or cease functioning. The chemical transformations that occur continuously in our bodies – like extracting energy from food or ‘burning’ it with oxygen from our lungs – are the result of many such interactions organised, one after the other, in pathways. Taken together, they add up to what we call ‘metabolism’. Figure 5 gives a vivid impression of the complexity of this.

Figure 5 Colourful summary of the pathways that make up our metabolism (ignore the detail!)

Research in multiple disciplines, over long periods of time, means detailed knowledge about these pathways is gradually building up. It may be a logical design process that leads to a new drug, as in the case of Ozempic; or it may be an accidental discovery. Bacteriologists working on yoghurt in a Danish food business played an unexpected role in the development of gene therapy by spotting how bacteria defend themselves from dangerous viruses. It’s the extraordinary build-up of knowledge and discovery from labs all over the world that has led to the medical treatments we take for granted today. A point to reflect on next time we go for a routine blood test or swallow another aspirin or beta blocker

© Andrew Morris 5th February 2025