Do young teenagers rebel in every culture? So began a discussion in one science group about adolescent behaviour. “Why do they choose clothes and hairstyles to be ‘individual’, when really, they are slavishly following a fashion” asked a confused Patrick.” “Maybe they need to differentiate themselves from their parents’ tribe, but also identify with their own tribe” suggested Helen.

“I’m sure it doesn’t happen everywhere” interjected Jean; “I’d heard in Bhutan, young people wear traditional clothes and don’t rebel; it’s just in the West we’ve developed a youth culture”. “Isn’t it because we’ve gradually extended the transition process through ever more Higher Education?” Helen conjectured.

Wendy widened the scope by thinking of other primate species: “don’t young male chimps leave the family when they reach a certain age?”. Closer to home, Helen added her cat experience “she would have nothing to do with her gorgeous kittens, once they were weaned!”

This discussion touched on many of the factors involved in the transition to adulthood. According to a review of research in 2017, these include psychological, physical, social and economic influences as well as the family environment. In this blog we look at some of these.

Adolescence historically

Adolescence as we know it today is a relatively recent phenomenon, according to research reported in Scientific American. It describes the teen years as a “relatively peaceful time of transition” throughout most of history, with our contemporary concept of adolescence being a little over a century old. A study of nearly two hundred of today’s pre-industrial societies, shows that, in half of them, there was not even a word for adolescence. Teenagers spent almost all their time with adults, and antisocial behaviour in young males was absent or extremely mild in these cultures. The turmoil associated with adolescence in Western culture today represents, as Helen had surmised, an artificial extension of childhood.

The very existence of a transitional phase of life is thought to have emerged around 75,000 years ago, long after our species Homo sapiens had appeared on the scene, some 200,000 years earlier. It is thought to have been a by-product of the coming together of individuals in larger groups and bonding as pairs.

The nature of the adolescent stage is not universal – it is shaped by differences in cultures.

In the West, the transition to adulthood began to be extended during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as young people were expected to develop skills for working life before marrying.

Figure 1 Moving into the adult world through work

The sense of the individual grew stronger over the subsequent period of industrialization and, in more recent times, with the ability to exert more control over life events, personal expression became increasingly important. Independence and assuming responsibility for oneself have become hallmarks of successful transition to adulthood in contemporary western societies.

Puberty occurs earlier today than in previous generations (and also earlier than in modern hunter–gatherer societies). The gap this creates between biological and social maturity means that teenagers today are less likely to earn the respect or privileges of adulthood through work. It’s also less easy for them to learn from others of differing ages, because they spend so much of their time within their own age group. Since the late nineteenth century, group identity and norms in fashion, values and morality have tended to develop through the influence of the peer group rather than by adult role-models.

Cultural differences

The discussion group wondered about the ways in which the transition from childhood to adulthood occurred in other cultures. Wendy thought about hierarchical societies in which leisure, not work was the future for youngsters of the ruling class. “Surely, in some cultures people would grow excessively long fingernails or have tightly bound feet” Patrick argued; “active work was not to be for them” Jean thought about countries such as Japan and South Korea where young people are expected to study or work very long hours, leaving them with limited time for private life. Recent research on teenagers in Japan suggests that attitudes are changing rapidly today, with a growing sense of individualism amongst adolescents coming into conflict with the more collective culture of their parents.

In ‘non-Western’ cultures, the introduction of ‘Western style’ culture through schooling, television programs and movies, can lead to the turmoil and trouble associated with this phase of life, according to research reported in the Scientific American article mentioned above. Amongst the Inuit people of Canada, for example, the introduction of TV during the 1980s was soon followed by the new phenomenon of delinquency.

A particularly distinctive feature of many modern Western cultures is the separation of people by age, cemented most obviously by the way schooling is organised. Age segregation was not practised in human society until very recently, in evolutionary terms. It appears to increase aggressive tendencies and reduce prosocial behaviour, perhaps influencing the development of adolescent behaviour in Westernized cultures. In hunter-gatherer societies, by contrast, adolescents interact regularly with infants and young children, as well as with adults of all ages. Teenage boys join men on hunting expeditions, and girls join women in gathering activities. As a result, young people in the transitional stage are able to show their abilities and gain status without the need for rebellious confrontation.

In many traditional societies the transition to adulthood is celebrated through initiation ceremonies, which enable adult values and behaviour associated with the culture to be passed on.

Figure 2 Forest ritual for teenage girls in Java

Evolutionary perspective

Patterns of behaviour, as much as physical attributes, tend to develop gradually over the long haul of evolutionary time. If a change in behaviour leads to greater fertility, it will become more common in future generations, as greater numbers of offspring carry the advantageous genes. Some distinctive aspects of adolescent behaviour may have emerged over time in this way. The greater tendency to risk-taking, for example, could “increase social and reproductive success as it may be admired and confer status, especially to males”, according to one study. The greater number of offspring resulting from such ‘high status’ males may outweigh the risk of a shorter lifespan.

The physical environment can affect social and biological development too. The ‘adolescent’ behaviour of a type of grasshopper has been studied in varying conditions. When the ‘nymph’ (a juvenile) lives in low density surroundings, it will develop as a solitary adult; but, when conditions are more crowded, it develops as a social locust, destined to live life on the move instead. It’s the bumping together of legs in the crowd that drives the dramatic metabolic changes involved.

Evolution may also have led, in humans, to patterns of behaviour associated with environmental conditions. For example, girls born into unstable conditions, such as harsh or disrupted families are more likely to mature rapidly. It is possible that this trait has evolved over time because it enables reproduction to begin as early as possible, maximising the chances of offspring now, whatever troubles might lie in store later. By contrast, for girls born into stable conditions, a different pattern of behaviour was biologically favourable, involving stable pair-bonding with fewer partners and sexual restraint.

The teenage brain

Cultural and environmental factors clearly influence the way adolescents develop, as the research mentioned above demonstrates; but what about biological factors – in particular the growing brain – what part does this play?

The journey to adulthood means freeing oneself from emotional dependence on adults and developing the ability to govern oneself and to make decisions autonomously. Research in neuroscience is revealing how structural changes in the brain during puberty affect behaviour, particularly in two distinct areas. One is associated with rewards and the regulation of emotion (the limbic region). The effect of structural changes in this area results in an increased appetite for risk. Research confirms our anecdotal experience that adolescents and young adults are more likely than older ones to binge-drink, smoke, have casual sex partners and be involved in serious automobile accidents. This increase in risk-taking between childhood and adolescence is linked to changes in dopamine activity during this time, which encourage young people to seek sensation, especially when others of similar age are present. The peer group effect has been shown in many experiments to be an aggravating factor, meaning even greater risks are taken. It may be a consequence of close interaction between different circuits in the brain: those that process social information overlapping with others involved with seeking reward.

Fortunately, this risk-taking tendency in early adolescence begins to fade in the approach to adulthood, thanks to changes in in a different area of the brain: the prefrontal cortex. This area is associated with control of thinking and regulation of behaviour.

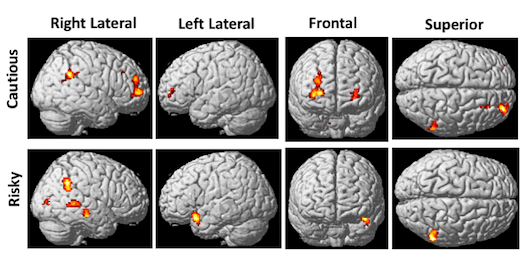

These scans of the teenage brain under both risky and cautious conditions show how the frontal region is more active in the cautious case, when risky tendencies are being moderated.

Figure 3 MRI scans of the teenage brain

However, the two systems in the brain develop at different rates. Reward-seeking increases early and fairly rapidly, whereas the capacity to self-regulate develops gradually, continuing into the mid-20s. As a result of this mismatch, the tendency to unregulated risk and recklessness is strongest in the middle period of adolescence. An article in Psychology Today points out that there may be an evolutionary explanation for this: to some extent, risk-taking behaviour may be necessary and important in helping young people acquire experiences that prepare them for adult life.

Research about the teenage brain often refers, wisely, to an “association” between how the brain works and the way in which we tend to behave, without spelling out which is the cause and which the effect. The review in Scientific American, mentioned above, reminds us that brain chemistry doesn’t necessarily drive our behaviour: “changes in the brain [are] associated with turmoil, as they will be with any behavioural change, but are likely to be the result, not the cause of the behaviour”.

Conclusion

This highly selective sketch of issues around teenage behaviour shows just how much can be gained by pulling together evidence from research in very distinct areas of science. As we have seen, anthropologists living in societies with widely differing cultures, help us put our own customs and behaviours in perspective. Archaeologists studying the bones of early humans are able infer something of the pattern of social and biological development in prehistoric times, thereby suggesting what may be wired-in genetically. Psychologists conducting experiments with groups and individuals are able to assess the effects of age, gender and other factors on actual behaviour today, while physiologists and neuroscientists measure the effects of hormones and brain circuits on our patterns of behaviour.

The net effect of such studies is to make us think more carefully about how adolescence is understood and accommodated in modern society. Are today’s conditions of schooling and working life, and especially the transition between the two, adding to the challenges that young people face as they prepare for adulthood? Do those societies troubled by teenage misbehaviour have something to learn from others in which the transitional phase is calmer and more enabling? Is teenage rebelliousness today simply a consequence of the way societies have developed in modern times? Whatever our view, it surely helps if we try to understand better what drives young people as they journey into adulthood.

© Andrew Morris January 2025