“What’s the force of a sneeze?” asked Wendy unexpectedly in a discussion about forces. At a stroke she’d switched the focus from rockets and planets – typically associated with force – to something closer to home – the human body. She’d jumped from the abstract world of mechanical and gravitational force to the everyday matter of muscles. What is it about muscle tissue that endows it with the extraordinary capacity to push, pull, lift and hold? How do muscles manage to keep the heart beating and fingers flying around the keyboard of a piano?

Sneezing is an unusually powerful action for the otherwise calm region of the face. The power comes from coordinated action by muscles in the chest and face. When foreign particles enter the nose, they can trigger nerve cells that send a signal to the brain which then instructs muscles in the throat to open it up. The signal also causes chest muscles to contract rapidly, forcing air out of the lungs – all aimed at expelling the foreign particles trapped in the nose.

How muscles contract

The amazing story of how muscles contract was worked out in ground-breaking research during the 1950s. Muscle tissue, as anyone who cooks meat knows, is fibrous. The fibres we see in meat are themselves made of bundles of smaller fibres (less than a millimetre across). Each one of these tiny fibres is a long thin cell – some may be as long as a muscle itself. These unusually long cells develop as an embryo grows, by the fusion of regular-size cells. It’s these long cells – the fibres – that have the extraordinary ability to contract.

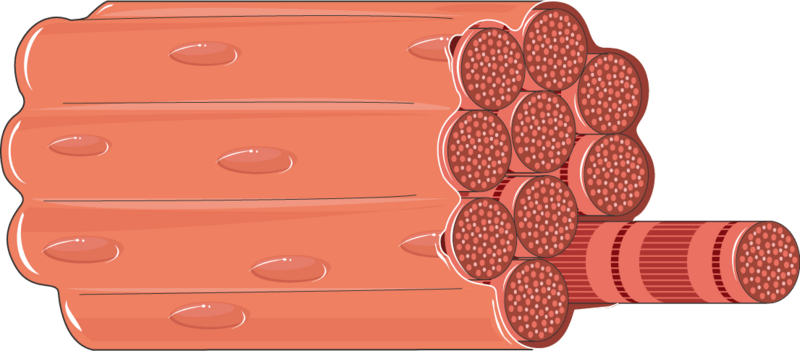

Within each fibre are hundreds of even smaller threads known as fibrils which do the contracting. Figure 1 shows part of a muscle fibre composed of many fibrils, one of which is protruding to show markings seen in a microscope.

Figure 1 part of a muscle fibre, showing the fibrils within it

Within each fibril are two different kinds of long, thin molecule, made of protein, which have the extraordinary ability to slide past each other. This causes the fibril, and ultimately the fibre and entire muscle, to contract.

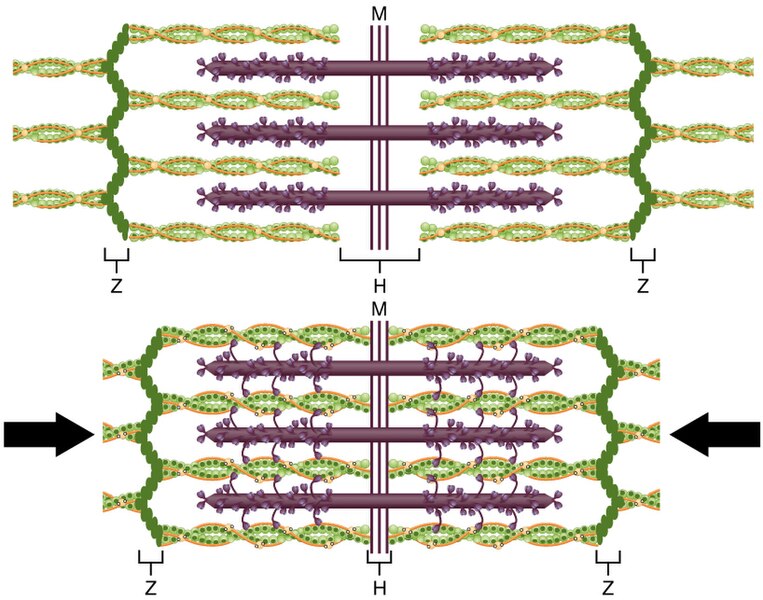

Of these two long, thin protein molecules, one called myosin (shown in red ) pulls on those on either side of it in pink (called actin), causing the unit to contract (figure 2). Coordinated action across millions of such units contributes to the overall pulling action of a muscle.

Figure 2 myosin molecules pulling actin molecules inward.

The precise way this happens is an amazing act of movement within a molecule. Figure 3 shows in more detail the molecules illustrated in the previous image.

In the upper half of the figure, the myosin molecules (purple – red in the previous image) are at rest. In the lower one, tiny little arms,spread along the length of these molecules, reach out to connect with the neighbouring actin molecules (green – pink in the previous image). Acting in concert, they then pull the actin molecules inwards, one step at a time.

Figure 3 Myosin molecules pulling actin molecules towards the centre

This action keeps repeating, shortening the muscle fibre a little with each step. This 30-second video shows in greater detail the remarkable way in which this happens: animation of muscle contraction.

When muscles are attached to bones (‘skeletal’ muscles) they can lift an arm or leg by tensing up. It’s a nerve impulse from the brain that triggers contraction. This signal causes molecules that store energy in the muscle cells (known as ATP) to kick off the sliding action. The action is voluntary, an act of volition; the arm moves because our brain instructs it to. Other kinds of muscle, ones we are less aware of, act without our brains being involved – we don’t get to choose whether or when they move. It’s these involuntary muscles that keep our heart pumping, blood flowing and food sliding through the digestive system. Imagine how risky it would be if we had to remember to contract our heart or push our food along!

Heart muscle

In heart muscle the fundamental mechanism is the same as for the skeletal kind: molecules sliding past each other. But the action isn’t triggered off by a nerve pulse from the brain; instead, it’s a local electrical event that kicks it off, autonomously. All cells are inherently electrical: they contain ions (aka electrolytes) which are atoms that have lost or gained an electron, upsetting the normal balance, making them electrically charged. Ions of sodium, potassium and calcium are examples in the human body. The heart contains specialised cells, called pacemaker cells, that are able to shift electrically-charged ions across their membranes, changing the tiny voltage between inside and outside the cell.

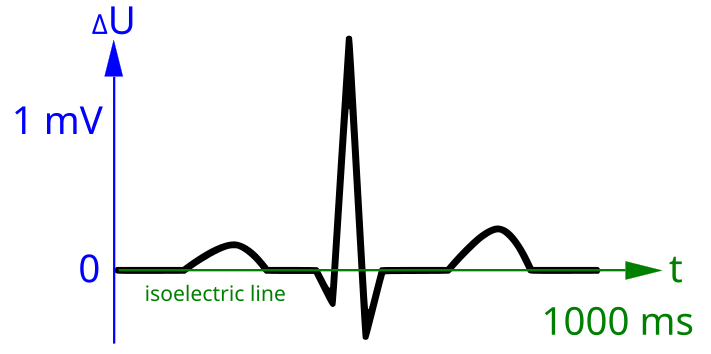

This creates a pulse which spreads across the heart muscle, causing it to contract. In effect the heart is creating its own nerve pulses internally and regularly, rather than depending on ones sent from the brain. It’s this changing voltage (only a thousandth of a volt) that is recorded on an electrocardiogram.

Figure 4 An ECG trace showing one heartbeat

‘Smooth’ muscle

A third type of muscle tissue is found in places in the body where contraction is needed for more sustained periods. Examples of this are: the propulsion of food through the digestive tract, the expansion of the iris and the stretching of hollow organs such as the bladder and womb. This so-called ‘smooth’ muscle contracts and relaxes more slowly than the other kinds of muscle and maintains its ‘tone’ (i.e. a degree of tension) even as it stretches or relaxes. Like heart muscle, it contracts without conscious control, thanks to the presence of pacemaker cells. These generate electrical pulses within the muscle itself to trigger contraction. Smooth muscle is also present in the arteries and veins, controlling their diameter, and hence blood pressure. The flow of air in the lungs is similarly regulated by smooth muscle. In other areas where flow needs to be controlled, such as the gut, the urethra and the womb, smooth type of muscles ensure both contraction and relaxation can be slow and steady.

This kind of muscle is described as ‘smooth’ because of its distinctive appearance at cellular level, under the microscope, not its external appearance. In contrast to skeletal muscle, it is not made of long thin fibres but of much shorter cells each of which contracts independently but in unison with its neighbours. The diagram in figure 5 shows a single cell before and after it contracts.

Figure 5 diagram of a single smooth muscle cell

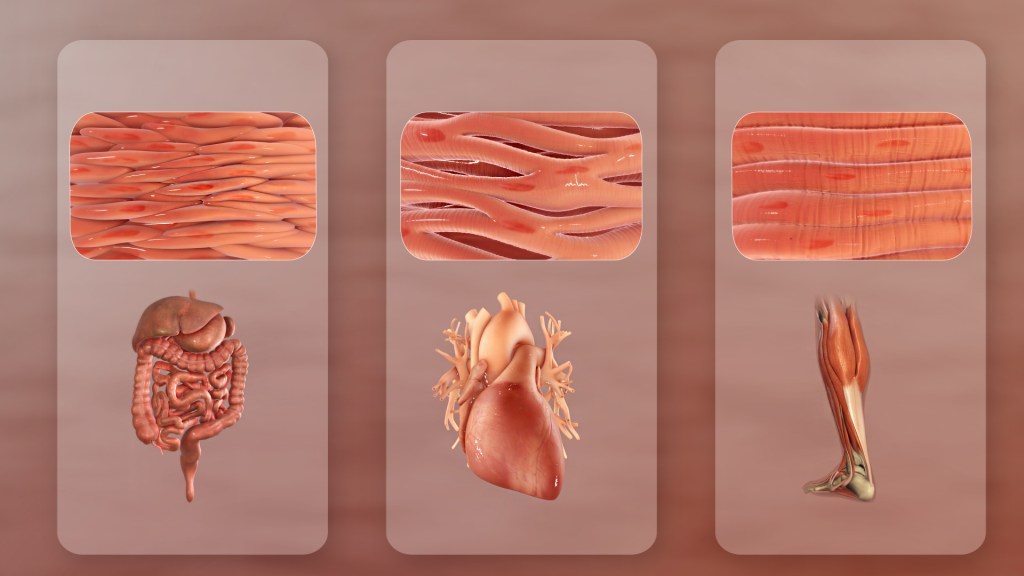

The microscope images in figure 6 compare the three types of muscle cell.

Figure 6 Three kinds of muscle cell: smooth, cardiac and skeletal

Energy

We have seen the mechanism by which muscles are able to contract. All three types depend upon the action of long thin molecules of actin and myosin sliding past each other. To make this happen, energy needs to be supplied as the molecules pull against each other. Each tiny tug of molecule on molecule in the contraction process in every cell consumes the energy delivered by one molecule of the body’s main energy carrier, known as ATP. Moving a muscle requires many cycles of such stepwise movement, each requiring a tiny burst of energy.

An analogous process occurs in the internal combustion engine of a motor vehicle. A tiny burst of energy is released with each cycle. A spark triggers off a chemical reaction in the fuel vapour, releasing the energy stored in it. In muscle, the nerve signal acts like the ‘spark’ and the energy-storing molecule ATP is analogous to the fuel vapour.

Figure 7 the stages of combustion in an engine

The energy required by muscle cells is supplied locally by molecules of ATP, but these have to pick up their energy-load from somewhere, too. This comes from the vast numbers of energy-rich glucose molecules that flow through the bloodstream and get absorbed into cells. And these glucose molecules themselves are come from the carbohydrate molecules we eat with every meal. That’s the link between food and physical activity: energy transfers in stages from food to glucose to ATP to muscles and brain cells, where it finally gets used to move and think. It’s no surprise that we feel tired and hungry after vigorous exercise: our muscles are crying out for more energy-rich glucose to replace all the ATP they’ve used.

Muscles in action

Our skeletal muscles are not only for occasional acts of lifting or running, of course. Humans, like many other animals, need to remain intact and upright most of the time. If all our muscles were suddenly to relax completely, we would simply fall to the ground in a heap. Our posture is maintained by an active balance of muscles in tension, attached to the frame of our skeleton. Muscles normally rest in a partially tensed state, ready to react either way – tense-up further or relax. The degree of partial tension in resting muscle is referred to as ‘muscle tone’.

Muscles attached to the skeleton frequently occur in pairs, pulling in opposing directions. This is necessary because, although a tensed-up muscle is able to pull, a relaxed one cannot push, so you need two for each action – they don’t have the two-way ability of a spring: tension and compression.

The movement of our arms for example, is effected by opposing pair of muscles. The biceps (on top) contract to raise the forearm while the triceps (underneath) are relaxed. The reverse happens to return the arm to its former position.

Figure 8 Opposing pairs of muscles – biceps and triceps

The production of energy-rich ATP molecules is a chemical process requiring a constant supply of oxygen. Under ordinary conditions, the oxygen we breathe is sufficient to keep up with demand. With more intense exercise, however, more oxygen is demanded – as any athlete knows. We breathe faster and more deeply to cope, but at some point this is no longer sufficient to deliver the required level of oxygen; an additional process is invoked, known as anaerobic respiration. This alternative pathway delivers energy rapidly, but, unlike the usual aerobic way, produces lactic acid as a by-product. It’s the build-up of this that causes the burning sensation and ultimately cramp of overworked muscles.

Conclusion

This story shows the wonderfully connected systems that enable our bodies to function from minute to minute. All physical movement (and indeed, all mental activity too) requires a steady supply of energy. The ultimate source of this energy is locked up in the carbohydrate molecules of which plants are largely made; and they, in turn, got it by basking all day in sunshine.

This energy gets transferred to our bodies through eating plants (or animals that have fed on plants). It’s held throughout our bodies in the form of glucose molecules, that our digestive system produces from the food we eat. When our muscles or our brains need to act, these ubiquitous glucose molecules are called upon to energise millions of ATP molecules located in the precise places where energy is needed. Deep inside the tiny fibrils of our muscles these ATP molecules drive the sliding mechanism that enables the fibrils to contract or relax, as and when triggered to do so. It’s a remarkable process, whose intricate stages have been pieced together over the course of the last eighty or so years, by countless studies in anatomy, physiology, biochemistry and biophysics. A triumph of collaborative effort by scientists, across disciplines and continents!

© Andrew Morris December 2024