Good versus bad cholesterol was the discussion point one evening, after Julie had seen the results of her recent blood test. She wanted to shift her diet to make sure she cut down on the bad version. This inspired a deeper discussion about food and health in general.

Sonya, who’d travelled in the far east, pointed out that diets differ quite dramatically across the nations, and that the incidence of illnesses varied accordingly. In Japan, where she had been, fish eating was linked to lower levels of heart disease. “Yes, but maybe they exercise more” chipped in Sarah. Patrick had read about a study at Glasgow university showing that cyclists suffer 45% less cardiovascular and cancer disease than the average, and walkers 25% less. Mary had heard that the fat from fish oil was better than from meat – what was the difference?

With such a panoply of questions, the group vowed to look more carefully at food labels in future, and decided to look into the nature of foods, and the way in which our bodies deal with them. So begins our journey down the digestive tract.

Brain and perception

It’s undoubtedly the smell and look that draws us most compellingly to food. Even before our mouths are engaged, the nose and eyes capture us. The mere sight of appetising food is enough to trigger a saliva response in the mouth. Clearly the brain is heavily involved. Signals from the eyes, ears and nose pass thorough nerves to the distinct parts of the brain associated with vision, sound and smell. Many studies look at what visual and aromatic factors affect our perception of taste; intense colour in food, for example, has been shown to enhance flavour and suggest freshness. The variety of colours in food is the result of the many pigments present in plants – chemicals that both capture energy from the sun and attract pollinators. Different pigments – orange, purple, red, green – confer different health benefits. Many act as antioxidants, protecting us from chemicals that cause damaging oxidising reactions in the body. Different pigments help protect against different conditions, including heart diseases and cancer. This is why nutritionists advise us to eat a rainbow of colours in our meals.

In the brain the multiple signals from our eyes, nose and mouth are brought together and integrated in multisensory areas before passing on to the pleasure system of the brain, where they are assessed for any potential reward. Neuroscientists map these areas of the brain using MRI scanning. Interestingly, studies in many fields, converge on the idea that we have a unified pleasure system in the brain, common across the range of sources of pleasure, including food, social interactions, sex as well as music and other hedonistic stimuli.

Hunger is, of course an important signal from within, stimulating the body to seek food. Interactions between the gut and brain indicate whether the digestive system is satiated or ready for more food. A hormone called ghrelin is released when your stomach is ready for more food and another called leptin, is released when it is full. These two hormones circulate in the bloodstream and are picked up in the brain, helping to regulate feeding behaviour (though other mechanisms are involved too). Habits, and behaviour learned socially, also play a role, as we know through the variety of mealtime behaviours, across cultures.

The brain also has to identify potential threats in food sources – toxins and microorganisms, for example. Taste plays a key role in this with the taste buds distinguishing rapidly between bitterness and acidity in contrast to sweetness.

Eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia, show us that none of the systems described above are simple. Hunger may not stimulate eating, not does the sight or smell of appetising food always do so. Research in genetics, brain imaging and psychology is active in this area and points to a mix of causes, including faulty chemical signalling in the brain, variations in genes and environmental experiences such as stress.

Mouth and nose

Long before your food reaches the stomach, work has begun on digesting it. Chewing begins the process of physically breaking up large pieces of food into smaller chunks, which increases the surface area for saliva to work on chemically. Saliva is released from glands in the mouth all the time (as much as a litre per day), but this increases rapidly when food touches surfaces in the mouth. Contained in the saliva are giant molecules, made of protein, called enzymes. This class of proteins act as the tools of the body, helping transform chemicals in various way, often by breaking the bonds that hold together the atoms in molecules.

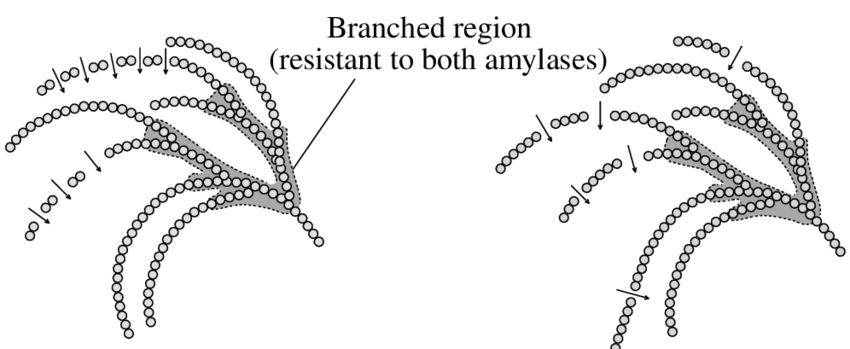

One type of enzyme in saliva, called amylase, breaks up the large, branched molecules of starch, a type of carbohydrate found in rice, pasta and potatoes (see figure 1). Another, called lingual lipase, breaks up molecules of fat. Saliva also helps by lubricating the mouth in preparation for swallowing.

Figure 1 branched molecule of starch being cut up by amylase

Once the molecules that make up food begin to be released into the mouth, the taste buds come into play.

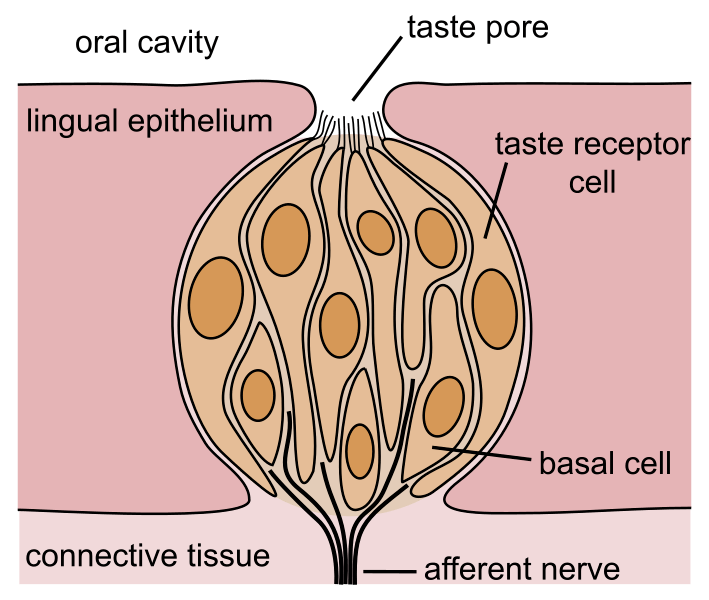

These tiny structures on the surface of the tongue, and elsewhere in the mouth, contain cells with tiny hairs just below an opening (‘taste pore’) through which molecules from food can enter.

Figure 2 Taste bud

These hairs contain receptor molecules which respond to specific kinds of chemicals in the food. Each type of receptor recognises only one specific type of chemical. Sugars set off the sweet taste, for example and acids set off the sour. Salty taste is actually the taste buds’ response to metal ions (electrically charged atoms) such as sodium, and the bitterness response is activated by a class of chemicals called alkaloids, of which caffeine is a prime example.

At this point in the discussion Sonya wanted to know how it is that detecting the presence of a certain type of chemical in the mouth leads to the sensation of taste. The objective answer is that when the chemicals that trigger taste (e.g. sugar or vinegar or caffeine) are detected by a taste bud, an electrical signal is sent from a nerve at the bottom of the bud which runs all the way up to the taste-sensitive area of the brain. The subjective sense of particular tastes is studied by psychologists working with neuroscientists. The taste detecting areas of the brain are intricately connected to another area, the limbic system, which is associated with emotion and memory. This links the presence of specific flavours to some combination of emotions, including pleasure and disgust, and also to memories of previous tasting experiences. Your personal upbringing, cultural norms in your community and previous encounters with specific foods all contribute to your emotional reaction. Some responses are part of our genetic inheritance – the pleasure of sweet things, and revulsion at bitter poisons, for example – and others are entirely personal, like the memory of a wine on a happy holiday, or a food we were forced to eat against our will at school.

The nose also plays a key role at this stage, picking up flavour molecules in the air, while the taste buds are at work. The olfactory bulb in the nasal cavity is capable of distinguishing around 10,000 distinct kinds of ‘smell’ molecule – known as pheromones. This huge range – much greater than the five types of the taste buds – allows for an almost limitless number of combinations of flavours. The olfactory bulb, much like the taste buds, transmits signals to the brain which interprets them in the context of emotions and memories. What we call taste is, strictly speaking, a combination of taste and smell (technically, gustation and olfaction).

Journey to the stomach

As we all learn early in life, our tongues play a vital role in propelling batches of saliva-soaked food down our throats into the oesophagus, to start their journey through the digestive system. A critical early step is preventing a wrong turn, down the windpipe (trachea), causing us to choke. The epiglottis performs this vital function by moving as soon as food is detected leaving the mouth. This flap of tissue holds the trachea open while we aren’t eating or drinking, so we can breathe normally, but closes it off when we swallow. This video of an MRI scan of swallowing shows the process happening, as a person swallows some pineapple juice.

Once the food is safely in the oesophagus, it’s passage to the stomach is assured, even if we’re lying down, or even upside down, thanks to the amazing, coordinated actions of peristalsis.

Layers of muscle within the tube of the oesophagus are organised so as to produce sideways squeezing behind the food and lengthways contractions in front of it. Together these produce a wave-like motion propelling the food down to the opening of the stomach

Figure 3 Peristalsis

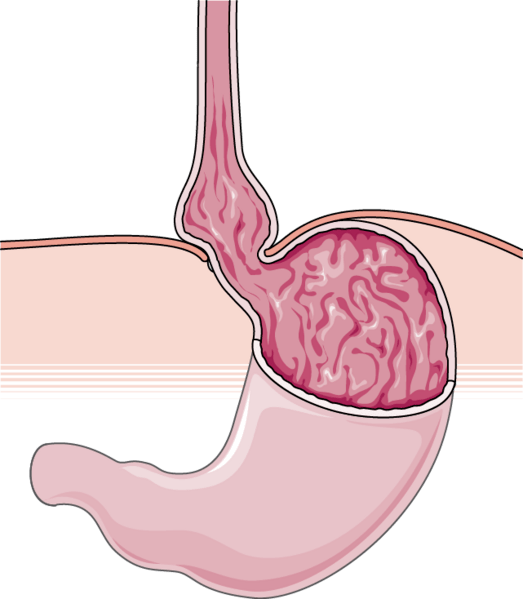

Here, at the entrance to the stomach, a strictly disciplined sphincter guards the entrance, making sure that none of the damaging acid within leaks out into the oesophagus. A leaky sphincter here, can give rise to the sensation of heartburn, as gastric acid backs up into the oesophagus.

The oesophagus has to pass through the large muscle that separates the abdomen from – the diaphragm. A hole in the diaphragm, called a hiatus allows for this, but, for many people, especially the over-50s, the upper part of the stomach may bulge upwards through this hole causing acid to flow upwards into the oesophagus. This condition, known as hiatus hernia, can be treated with medicine that reduces the production of acid in the stomach lining.

Figure 4 Hiatus hernia

Stomach

It may come as a surprise, but the stomach doesn’t actually absorb food – that comes later.

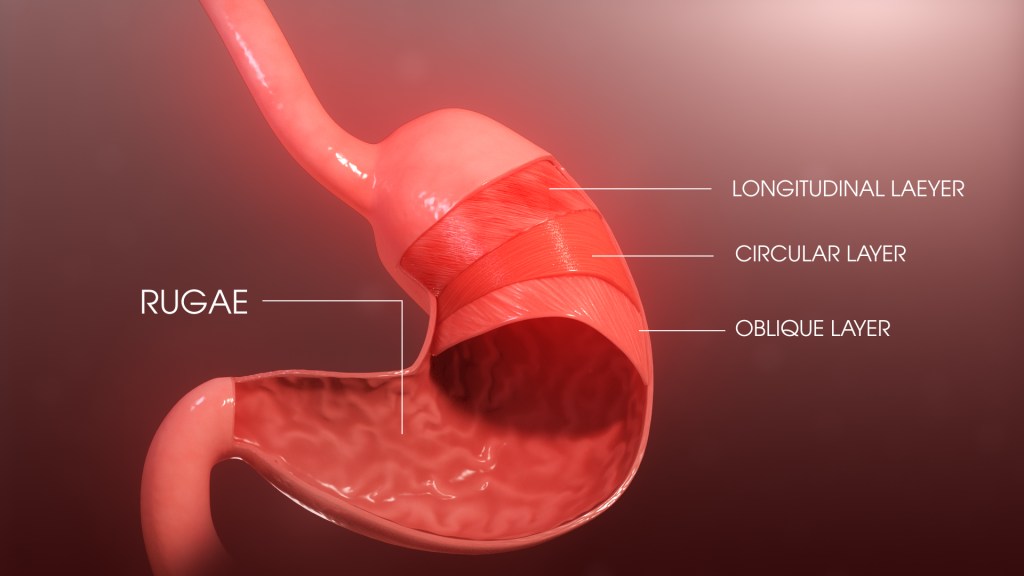

It’s a muscular organ that squeezes and churns, turning the gooey batches of food and saliva entering it into a liquid (called chyme), ready to flow out, along the digestive tube of the intestines (figure 3). Layers of muscle are arranged in different orientations to maximise churn.

Figure 5 Stomach, showing orientation of muscle layers

This ‘chyme’ is not just any liquid, it’s a highly acidic one, as anyone who’s suffered heartburn will know. The acid – hydrochloric – is produced in glands in the stomach wall. It has several effects: unravelling the long chains of protein molecules in our food, breaking down fibres and killing bacteria. But most importantly, it activates a harmless enzyme that is released from the stomach walls, turning it into an active protein chopper.

The latter, a vital enzyme known as pepsin, works on the long chains of protein molecules, unravelled by the acid. It breaks the bonds holding together the subunits (called amino acids) of which protein chains are made. This makes them small enough to be absorbed further on.

Figure 6 Proteins are long chains of amino acid subunits

The liquid churned up in the stomach (chyme) is squirted into the small intestine by a wave of muscle contraction in the stomach forcing open the sphincter that leads into the intestine. A full stomach empties in a few hours, depending on the make-up of a meal; it then closes down its acid production, and awaits the next bout.

This journey down the tract is already quite long. If you are short of time this is a good place to take a break. If you have the time and curiosity, however, you can continue the next stage, through the intestines, in the READ MORE section, below.

© Andrew Morris August 2024

READ MORE

Small intestine

Now the business of digestion really gets going, keeping us alive by extracting energy and nutrients from the partially broken-down items in the chyme. More work needs to be done to reduce the large molecules still remaining, into smaller ones, capable of penetrating the lining of the intestines and entering the bloodstream. To do this, molecules need to be not only small enough but also ready to pass through the oily walls of the cells that line the intestines (aka gut). A whole suite of enzymes is released into the intestine, each one specialised to break bonds in either proteins or sugars, starch or fats or DNA. These digestive enzymes are produced in glands in the pancreas; over a litre of this pancreatic juice is produced each day, on average. This vital fluid not only contains the tools to chop up molecules in different kinds of food, but also plenty of solid bicarbonate which neutralises the stomach acid, thus protecting the walls of the intestine. It’s no accident the pancreas is located close to the beginning of the intestines, ensuring acid doesn’t enter and damage their lining. Fats tend to aggregate into globules, making it harder for the enzymes that break them down to work effectively. For this reason, a liquid known as bile is produced, which contains chemicals that break the large globules up into smaller ones (‘emulsifies’ them).

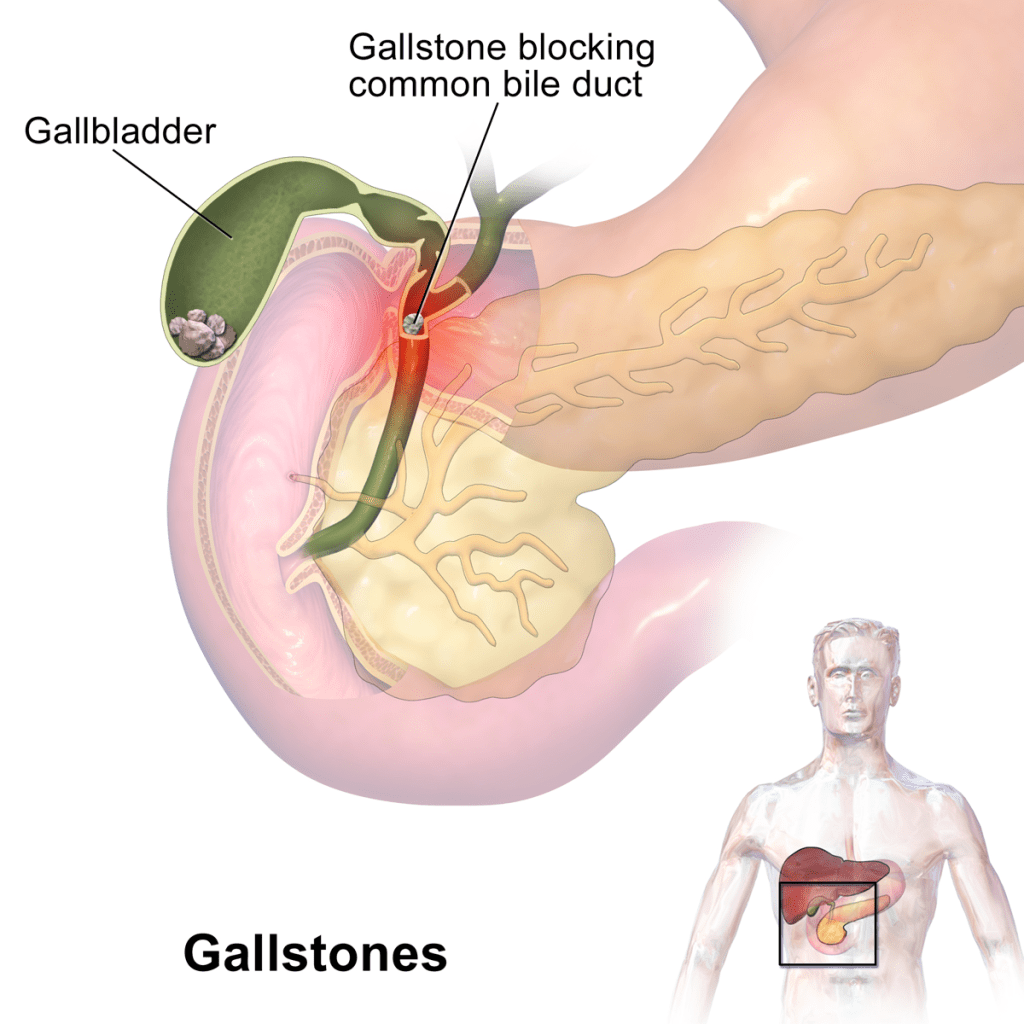

Bile is produced in the liver and stored in the gall bladder, ready to be deployed when fats are detected. If material in the duct that delivers bile to the intestines builds up to form gallstones, this whole process can be blocked, making digestion of fats more difficult. The gall bladder may be removed surgically to remedy this; bile then gets stored in the duct rather than the missing bladder.

Figure 7 Gall bladder supplying bile to the small intestine

Figure 7 shows the ducts from the gall bladder and the liver (not shown) supplying bile juices to the small intestine (pink). A gallstone blocks the path.

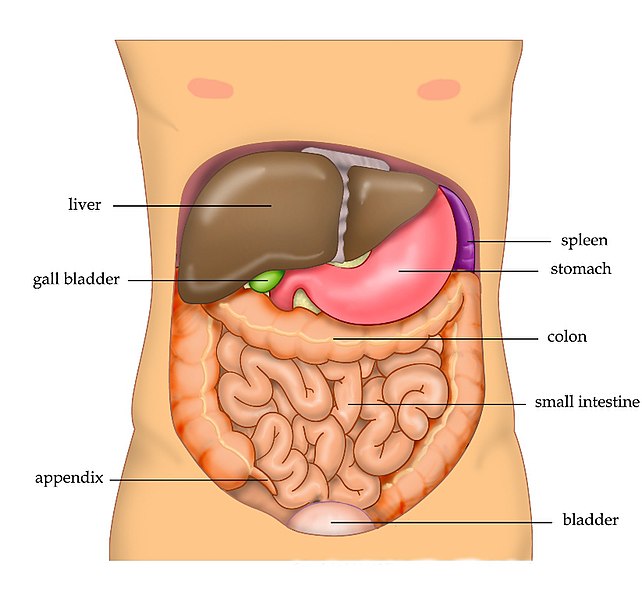

The wonderful, tightly-packed arrangement of the various organs involved in digestion is shown in figure 8. (The spleen is not directly involved in digestion – its role is to remove old blood cells and store of blood in case of emergency).

Figure 8 arrangement of organs in the abdomen

Now the task of absorption really begins. Your food has been chewed, churned, broken down and liquified; it’s time to sort out the valuable part and absorb it, leaving the rest to be expelled. As we learn from nutritionists, we need carbohydrates and fats for energy, proteins for muscle building, and vitamins and minerals for our metabolism (i.e. the chemical reactions that keep us going). So how do all these substances get out of the gut and into the rest of the body? Several modes of transport take molecules of different sizes and kinds through the cells that line the gut and on, into the surrounding blood and lymph vessels.

Most molecules are actively transported by special proteins embedded in the membrane of the cells that line the gut.

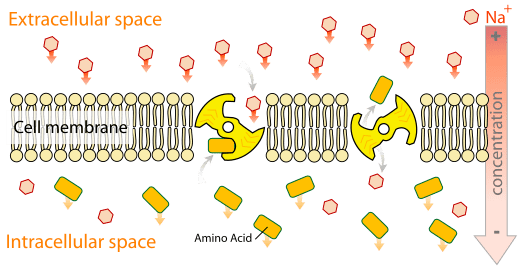

Figure 9 Active transport across a cell membrane

These stick out into the interior of the intestines to pick up the molecules from food; they then literally turn around within the membrane in such a way that the molecules they have picked up are now facing into the cell, ready to be released inside.

Figure 9 illustrates a giant molecule, embedded in the membrane of a cell (the big yellow thing), picking up a small molecule (amino acid – orange rectangle) turning around and releasing it on the other side of the membrane. What an amazingly sophisticated process! It’s taken countless studies over decades, throughout the world, to develop such an intimate picture of what is happening.

A similar process gets the food molecule out of the other side of the cells that line the gut, and into the cells that line the adjacent blood and lymph vessels, finally releasing them into the bloodstream and the lymph system. The whole process is like a series of diggers, picking up a load in one place, turning around 180° and dumping the load, ready for another digger to do the same until the load reaches its destination.

But it’s only small molecules that can make it across these barriers in this way, into the bloodstream. The molecules arriving from the stomach – carbohydrates, fats and fragments from proteins – are too large and need to be broken right down to their smallest subunits to pass through the walls of the intestines. A variety of specialised enzymes located in the lining of the gut do this by breaking bonds that hold large molecules together. Some molecules we imbibe, such as water are already small, and are able to squeeze through the tiny spaces between cells.

For all this absorption activity to take place, there needs to be a huge area of gut lining in which molecules from food can interact with the various enzymes and transporter molecules that carry out the process of absorption.

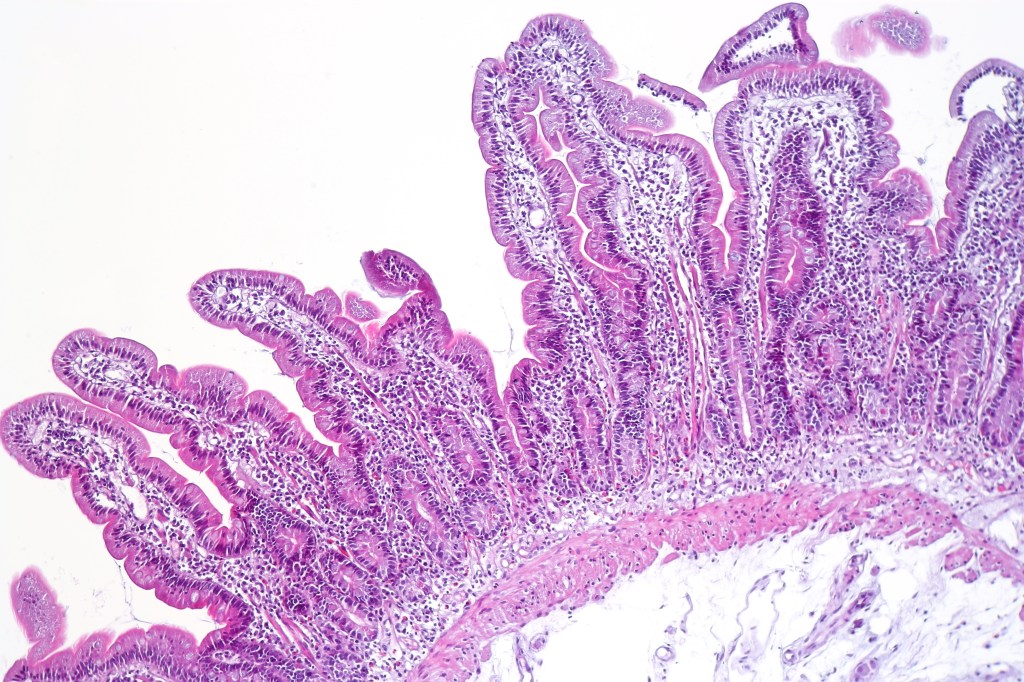

To make this possible, the inner lining of the gut is not a flat, smooth surface, like the inside of a tyre. Instead, it is a highly indented surface – like a map of the fjordal coast of Norway – and is covered with tiny protrusions (called villi), sticking out as blades of grass do in a lawn (figure 10).

Figure 10 Lining of the small intestine

The net effect is to multiply the actual surface area of the lining six hundred times, making it equivalent to half the area of a badminton court.

In the villi (the protrusions), tiny capillaries of the blood system and lymph vessels run close to the cells of the lining, into which molecules from food are transported.

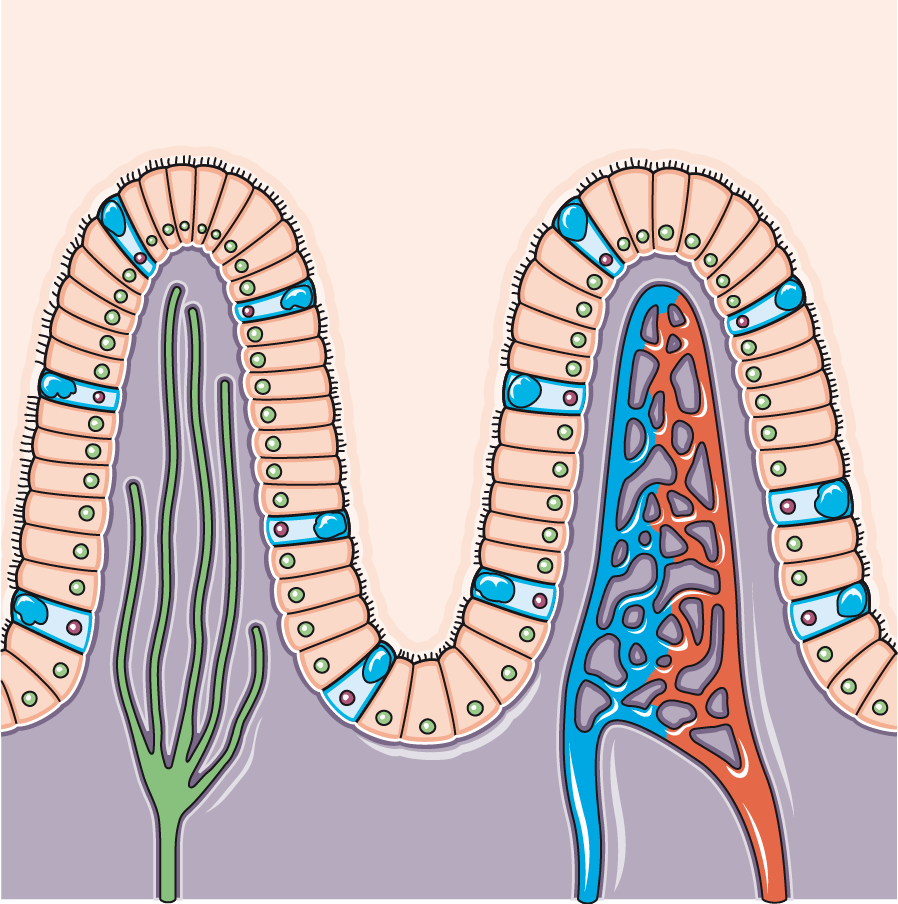

Figure 11 shows the single layer of cells that line the gut, folded into two ‘villi’.

Figure 11 Two villi in the lining of the gut

Inside these villi lie the blood vessels (red and blue) and lymph vessels (green) that take up the small molecules from food that have been absorbed through the lining of the gut. It’s from here that these nutrients are distributed to cells throughout the body.

Once in the bloodstream, molecules need to circulate freely to all parts of the body. This is straightforward for molecules that dissolve easily in water, such as proteins and carbohydrates. Fats, however, don’t dissolve in the blood and so cannot circulate. For this reason, they get loaded into larger particles, called lipoproteins that carry them around. These are the HDL and LDL – the so called ‘good’ and ‘bad’ cholesterol that launched the discussion on which this blog is based.

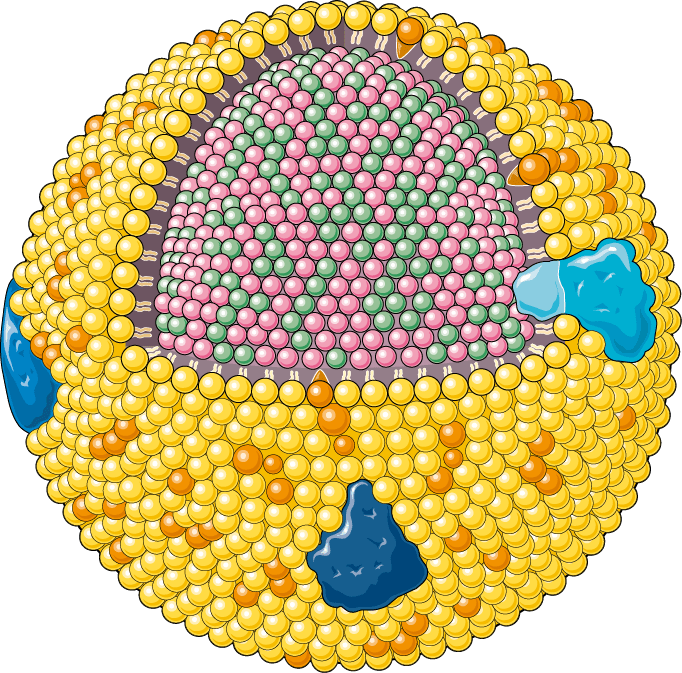

These lipoproteins have a beautifully arranged structure, which solves the transport problem; they are covered in molecules that have two different ends (figure 12). Their heads are water-loving (yellow balls) and their tails are fat-loving (short beige lines). Assembled together in a ball, they provide a coat that encloses the fatty molecules cholesterol and triglycerides (red and green) on the inside, but which itself dissolves comfortably in blood.

Figure 12 Model of a lipoprotein. (Image credit Servier Medical Art)

There are several kinds of lipoprotein, of which two – high density (HDL) and low density (LDL) – known as ‘good’ and ‘bad cholesterol, were the starting point for this discussion. Both are essential for carrying fats around the body. The colloquial name is misleading: it’s not actually the cholesterol that can be ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but the lipoprotein container that carries it around. LDL is known as ‘bad’ cholesterol because high levels of it are associated with blockages in the blood vessels, linked to coronary heart disease. HDL, on the other hand, is dubbed ‘good’ as high levels of it lower the risk of coronary disease, by removing excess cholesterol and disposing of it via the liver.

Large intestine

By the end of its six-meter journey through the loops of the small intestine, almost all the valuable nutrients have been removed from the tube of the gut and absorbed through its walls into the blood and lymph systems. But there’s more to be done; the remaining, unwanted material needs to be removed from the body, to make room for the next bout of feeding. That’s the job of the large intestine (aka colon).

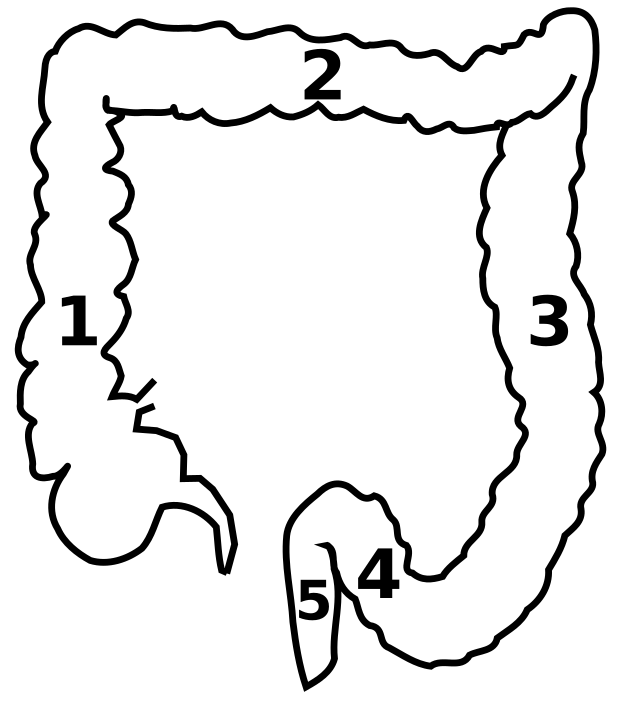

In contrast to the wiggly coils of the small intestine, this part is neatly organised around three sides of a quadrilateral (figure 13), one side ascending (1), one transverse (2) and the other descending (3). Its main job is to solidify the remaining material by removing water.

Figure 13 The sections of the colon

A much shorter tube is required for this, running to around two metres, with a surface area about fifteen times smaller than the small intestine (named after its diameter rather than its length). Absorption takes place throughout the colon, but the last third, the descending section, acts as a store, preparing for excretion.

The inner surface of this area can become inflamed or ulcerous, giving rise to irritable bowel syndrome. It can also be the location of tumour growth in colon (aka bowel) cancer. Detected early this can be cured – hence the extensive screening programme. It is less common for people who eat a healthy varied diet without excessive red meat, exercise regularly and don’t smoke.

From the bottom of the descending colon, the tube takes a dramatic couple of turns (position 4 in figure 10), creating a kind of U-bend which enables gas to accumulate at the top of the bend. This enables gas to be safely released without the solid.

The final stages of this epic journey along the gastrointestinal tract, bring us to the 12 cms of the rectum (position 5 in figure 10) and the 4 cms of the anal canal. The first of these acts as a storage space for accumulating faeces. As these build up, the walls of the rectum stretch to accommodate them. Nerves in the wall sense the degree of stretching and at a certain point signal to the brain the need to defecate. The strong muscles of the external sphincter in the anus are tightly contracted most of the time, ensuring this doesn’t happen involuntarily (usually). The act of defecation is normally a voluntary act, involving relaxation of the sphincter muscles when the time seems right, and often an extra push from abdominal muscles.

Gut bacteria

Havng completed a journey through the gastro intestinal tract, the discussion group were keen to explore one final topical issue: gut bacteria. Research is showing that our intestines don’t work alone. Living organisms, including bacteria and fungi (yeast in particular), not only co-exist with us, but are extremely numerous in our gut, contributing to our wellbeing. They help with the digestion of fibre and the production of vitamins B and K. Research also suggests that some inflammatory and autoimmune conditions are associated with weaknesses in the profile of the gut flora population. We pick up these vital microbes very early in life – initially, during the passage through the birth canal. Others are acquired from the environment throughout life. We can improve the quality and diversity of our gut flora – after a course of antibiotics for example – by consuming naturally fermented products, such as kimchee and kefir – or even some yoghurts or cheeses.

.

Conclusion

© Andrew Morris August 2024