Jean had been told some of her lymph nodes were blocked following her successful treatment for cancer. She’d seen them lit up on a scan. Everyone in her discussion group had heard about these mysterious parts of the body, but no one knew what they actually were. Rosemary said that a friend of hers had recently had a lymphatic massage – “what was that about?” she asked.

As discussion developed it became clear that these ‘nodes’ were just one part of a larger, coordinated system in the body. In fact, this is just one of many systems in the body upon which our lives depend. They complement other aspects of the body we more commonly talk about, the organs and tissues. In this blog we look at three of these systems: lymph, blood and hormones.

Lymphatic system

Lymph is a thin fluid that permeates the whole body, cleansing it as it travels. It begins its journey as plasma – the basic fluid of blood without the red, white and other cells. This colourless liquid seeps through the walls of the very fine blood vessels – the capillaries – that suffuse our entire body. The pale fluid enters the spaces been the cells of our bodies (interstitial space) and spreads, picking up chemicals expelled as waste from cells, and any unwanted toxins floating around. It’s a kind of road-sweeper function.

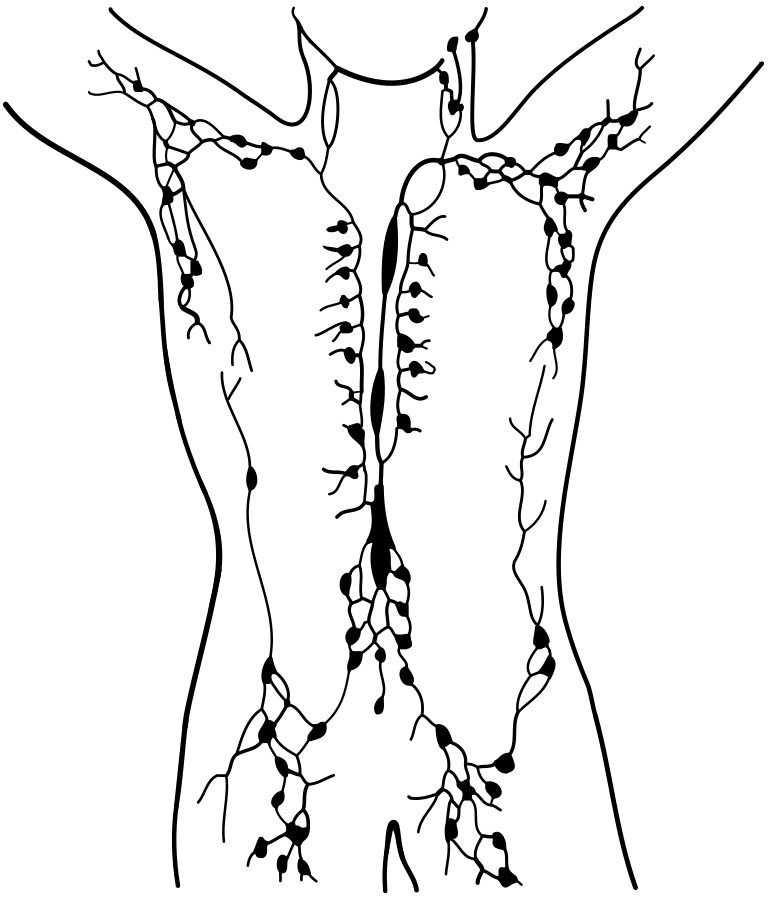

Figure 1 Network of lymph vessels with heart and spleen.

Loaded up with debris this cleansing fluid – lymph – needs to find its way to an exit. It diffuses through the interstitial space until it meets a lymphatic vessel. These fine vessels are present throughout the body and, crucially, their walls are permeable. Lymph fluid is able to pass through the walls of the lymphatic vessels to continue its journey.

It moves along these vessels, which then join up with others, and finally drain into one major lymphatic duct. This final segment of the lymphatic system feeds into the large vein that circulates exhausted blood back to the heart. Thus, the lymph, which started its journey as plasma leaking out of the capillary vessels, returns to the blood system, close to the heart, replenishing the stock of plasma.

The answer to Rosemary’s question about lymphatic massage is easily understood once the ‘drainage ‘function’ of lymph is understood. This treatment may be needed if too much fluid stays in the interstitial tissues of the body, causing swelling. This is a sign that the fluid is not passing properly into the lymph vessels, to be taken away. Gentle massage of the affected areas by a specialist can help move the fluid into the vessels.

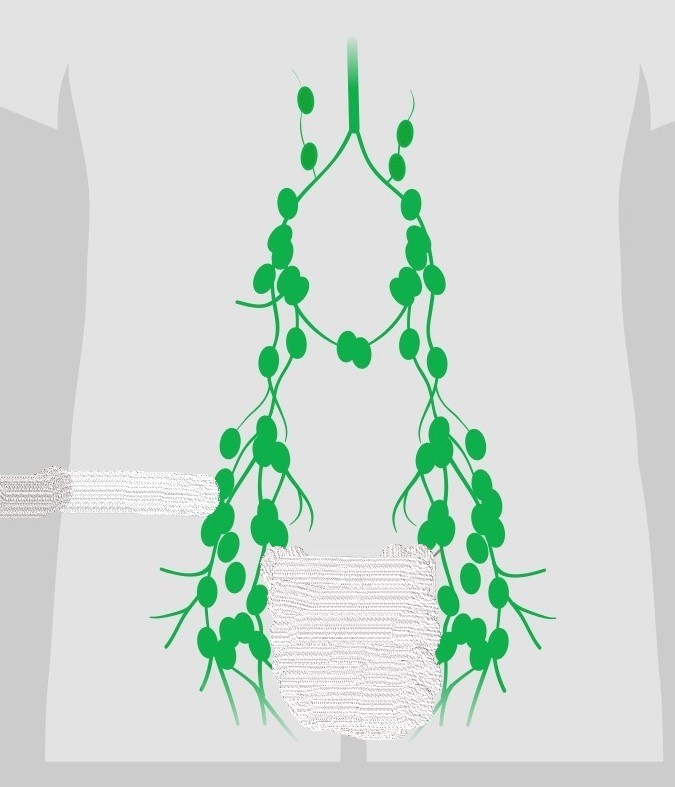

The immediate question on Patrick’s lips in the discussion group was a pretty obvious one: how does lymph move –there doesn’t seem to be anything like the heart to pump lymph around? Indeed, there isn’t – instead, it moves along thanks to an ingenious system of synchronised squeezes.

The walls of the lymph vessels have tiny muscle cells which contract to squeeze the tube. But how, you might ask, does just squeezing get it moving in the right (or indeed any) direction? Squeeze a water-filled hosepipe and water would squirt out equally at either end.

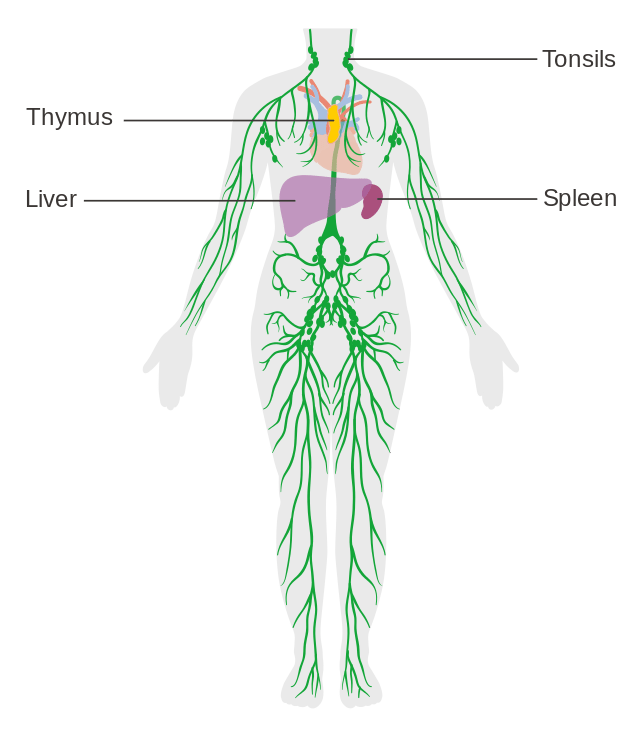

The trick is that lymph vessels are divided into compartments, like locks on a canal; and a one-way valve separates one compartment from the next.

Figure 2 Lymph vessel showing valves

As the muscle squeezes, the lower valve closes, preventing back flow, and the upper one opens, enabling forward movement. In this manner, the fluid only moves in one direction. Ratcheting up in this cunning way, the fluid gradually rises through the body, until it reaches the heart.

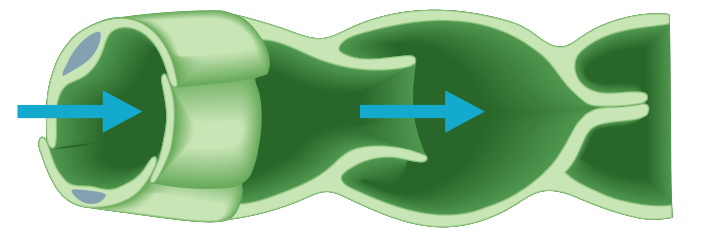

On the way, however it passes through a number of way-stations, punctuating the network of vessels: the nodes. “Yes – what exactly are lymph nodes?” asked Jean, whose cancer treatment had involved particular attention to these. Patrick had lost quite a few in his prostate cancer treatment, to minimise the risk of cancer cells spreading. Others in the group were aware that lymph nodes can swell up during infection – in the armpit or groin area, for example.

Lymph nodes occur at frequent intervals along the path of lymph vessels. They are bulbous structures around a centimetre across, packed with specialised defence cells called lymphocytes. These are capable of destroying unwanted items brought to them by the cleansing work of lymph fluid – bacteria and viruses for example. It’s one of the many ways in which the immune system combats pathogens.

Figure 3 Network of lymph nodes (simplified)

This is one reason why these nodes may swell up during infections – they get packed to the gunwales with lymphocytes, which multiply to destroy unwanted viruses and bacteria.

Lymphocytes play a key role in protecting us from infection. They originate as stem cells in the bone marrow but, in order to distinguish alien material from the body’s own cells, they need to be ‘trained’ in the presence of undesirable antigens. Other parts of the overall lymphatic system, including the thymus and spleen, are involved in this process of adapting lymphocytes, so they are capable of combatting the huge variety of potential pathogens.

Unfortunately, the network of lymphatic vessels can also serve as a conduit for rogue cancer cells that have broken away from a tumour. This may enable them to relocate to other areas of the body, spreading cancer – a process known as metastasis. In anticipation of this threat, Jean had had several lymph nodes removed from her body as a precaution, as had Patrick after his cancerous prostate had been removed. Lymph nodes are plentiful, with around six hundred in a typical human body; losing a few to avoid cancer spreading is considered acceptable. Unfortunately, lymph cells themselves may also become cancerous. In the disease lymphoma, lymphocytes cease to function properly and multiply uncontrollably. There are different types of lymphoma, depending on the type of lymphocyte affected. Fortunately, treatments are available for many of these types, some of which can be highly successful.

Blood system

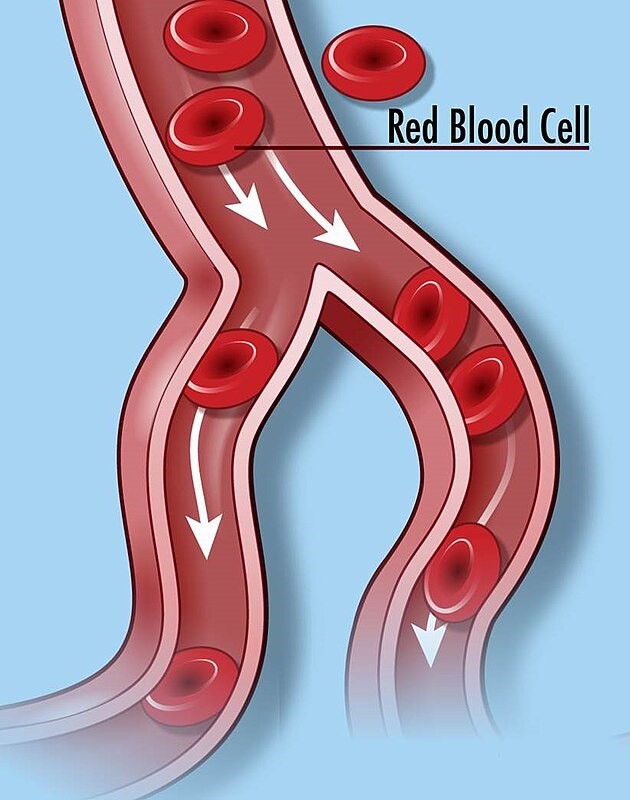

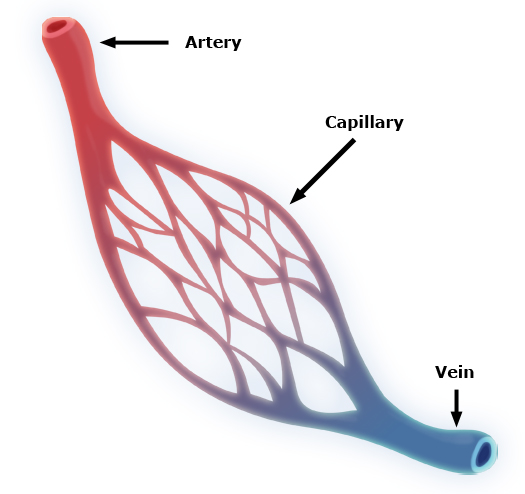

Lymph fluid begins its journey through the body, as plasma seeping through the walls of the capillaries. These ultra-thin blood vessels are just one hundredth of a millimetre across (a little thinner than a human hair), with walls only one cell thick. They are just wide enough for a red blood cell to pass along. Thin though these tiny vessels are, they reach every part of the body, and add up to thousands of kilometres in total length. These are the business end of the blood system.

It is here that the oxygen molecules pass from the red blood cells that have transported them from the lungs, through the thin walls of the capillaries into the space around them (the interstitial space) and, from here, into all the cells of the body. Oxygen molecules are essential for the survival and functioning of (almost) all cells – they use it to ‘burn’ the sugar molecules coming from the digestive system, releasing the energy stored in them.

Flowing blood transports oxygen molecules from the lungs to capillaries all over the body. Until the seventeenth century it was believed that blood was generated in the liver, and then diffused though the body where it was burned like a fuel. In 1628, a remarkable physician, William Harvey carried out careful measurements of the actual quantity of blood in the body to prove this can’t be true; it must be continuously reused by circulating around and around. He originated our modern understanding of a closed system in which the heart acts as a pump, pressurising the blood, enabling it to circulate, operating much as our and domestic water supply and heating systems do today.

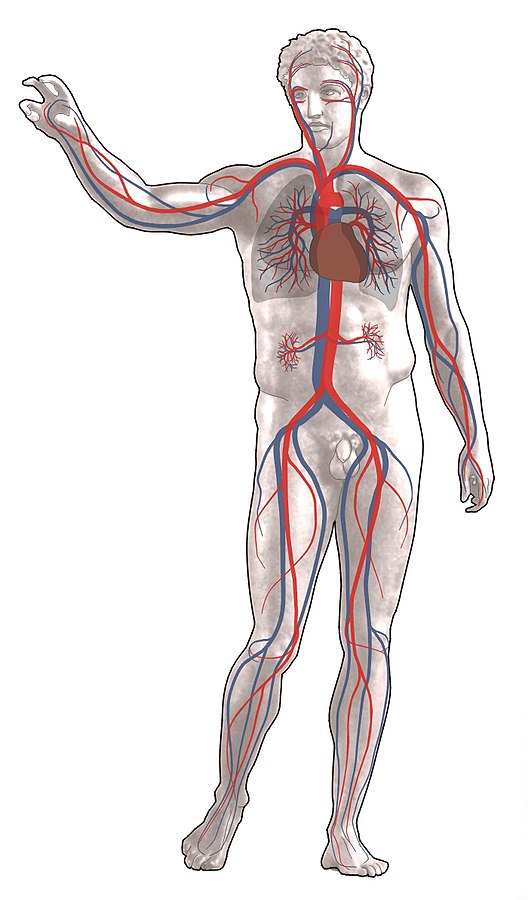

Figure 5 Main arteries and veins.

Large arteries, beginning with the aorta, carry oxygen-rich blood away from the heart. These branch into smaller arteries which spread throughout the body branching into ever smaller vessels, ultimately into capillaries.

In the capillary regions oxygen molecules start passing out through the walls of the blood vessels into the surrounding tissues. Further along the capillaries, carbon dioxide molecules – the waste product of cells’ burning process – begin to enter though the walls, into the vessels, from the surrounding tissue. From this point onward the same vessels are renamed, veins. They return the red cells depleted of oxygen, back to the heart.

Figure 6 Network of capillaries

Although blue and red colours are often used to distinguish veins and arteries in diagrams, returning blood, lacking oxygen, is not in fact blue, but simply a darker hue of red than that of arterial blood. Veins gradually merge with one another like tributaries to a river, until they reach the biggest of all – the Vena Cava – which empties into the heart. A separate set of blood vessels then pump the exhausted blood back to the lungs where the red cells get loaded up with oxygen molecules once again, ready for the next cycle.

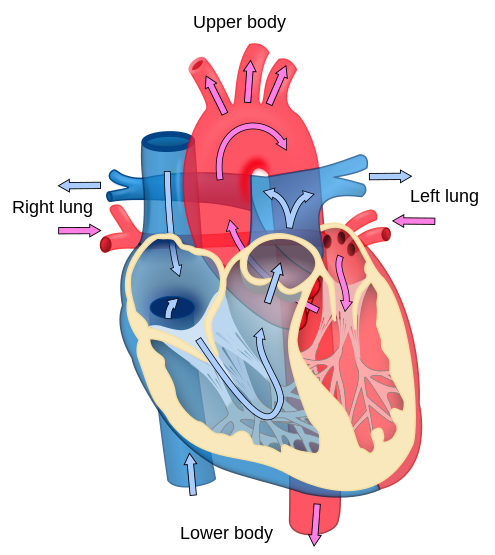

The heart, not only needs to pump out oxygen-rich blood across the body and to receive it back, depleted, it also needs to get the blood to and from the lungs, to pick up fresh oxygen and dispose of unwanted carbon dioxide. It has four chambers to accomplish this complicated task.

Figure 7 flow of blood through the heart

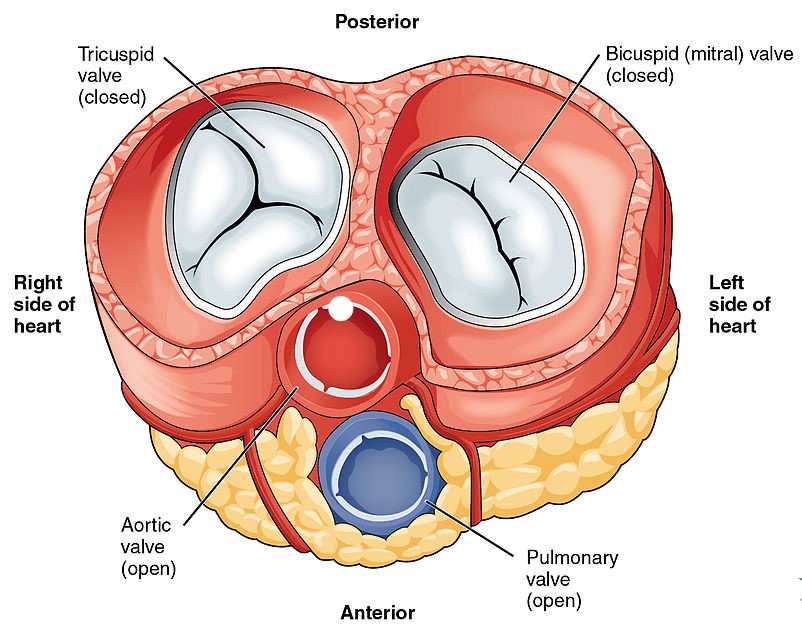

These are equipped with valves that open and close in a carefully controlled sequence.

Figure 8 action of a valve

The four heart valves are shown in a cross-section model of a heart in Figure 9. It depicts a moment in the cycle when two valves are closed (white) and two are open (red and blue). Valves are also present in veins to ensure the returning blood, less pressurised, still flows in the forward direction only.

Figure 9 diagram of valves in the heart

Endocrine system

But of course, it’s not only oxygen that gets transported around the body by the blood; so too do sugars, fats, proteins, vitamins, antibodies, drugs, hormones, and many other substances. Hormones are substances that are created in one part of the body but carry out their function in another. The bloodstream enables them get aournd the body to wherever they are needed. Adrenalin, for instance, is produced in glands near the kidney but acts on the muscles, heart, and other organs across the body. Hormones are messengers which are sent out, when required, to activate a function – lactating, running for your life or bringing on sleep, for example. The endocrine system is the name given to the whole system, comprising the hormones themselves and the glands where they are produced.

The main glands include the thyroid, pituitary, adrenal as well as the testicles and ovaries. Inside a gland, a complex series of chemical reactions take place to produce the hormone, each step in the process mediated by a specific enzyme. For example, the hormones oestrogen, testosterone and progesterone are all produced from cholesterol molecules by the action of enzymes. A particular class of hormones act as controllers, sending signals from one gland to another, to stimulate the release of a different hormone elsewhere. For example, ‘growth hormone–releasing’ hormone is produced in one organ (the hypothalamus) and released into the bloodstream. When it reaches the pituitary gland it stimulates the production of the growth hormone, as its name implies.

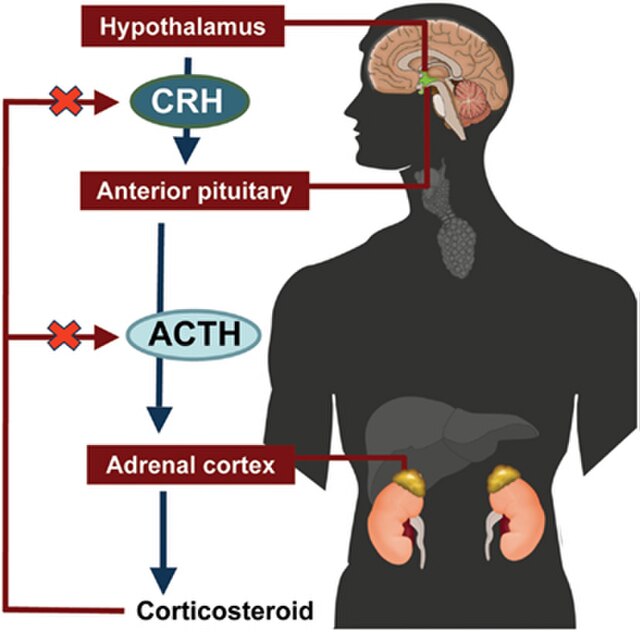

This interaction between hormones – one controlling the release of another – is a key feature of the way bodily functions are controlled and coordinated. In one particularly interesting example, fear induced by a threat can cause electrical signals from a part of the brain called the hypothalamus, to impact on a nearby gland, the pituitary.

Here the electrical signal causes the gland to release a hormone (known as ACTH) into the blood stream, which travels to the adrenal glands far away, near the kidneys. The arrival of this hormone stimulates the release of other hormones, of which cortisol is the most well-known. These in turn act in multiple ways on the heart, nerves, digestive system, enabling the body to respond to the perceived threat in a ‘fight-or-flight’ response.

Figure 10 Example of a brain – hormone system

This whole system can also be activated by other causes: physical activity, stress, the daily rhythm of sleeping/waking and by illness. This is just one of several pathways by which events in the nerve cells of our brains connect to actions in the rest of the body, regulating functions such as reproduction, digestion and immune responses. Emotions and thoughts in various parts of the brain are accompanied by electrical signals which, in turn stimulate hormonal responses that activate the body. For example, our faces are made to blush physically when our brains register embarrassment; or our hearts may ‘leap’ when we are overjoyed.

Interestingly, the very hormone produced at the end of the sequence illustrated above – cortisol – also acts to inhibit the hypothalamus and pituitary gland that caused it to be produced in the first place. This is an example of a negative feedback loop, which ensures that a hormone is not over-produced. Once there is enough of it in circulation, its increased presence slows down its own production.

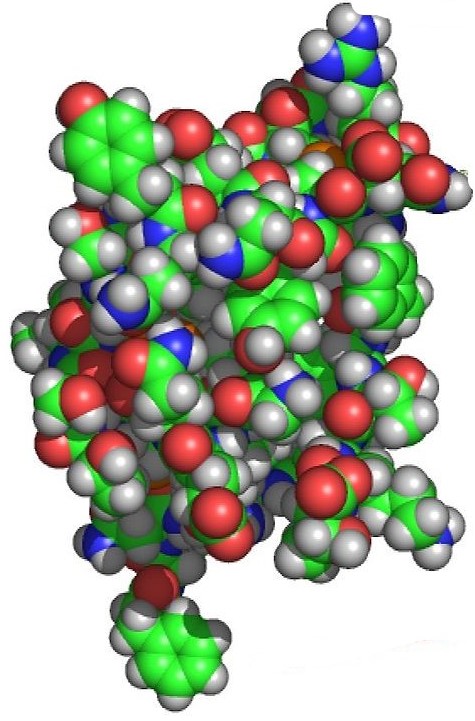

Although hormone molecules share a common function – taking messages from one part of the body to another – they differ markedly in size and structure. Some, such as insulin are large protein molecules. This hormone which regulates the absorption of the sugar glucose, is made up of 784 atoms (see figure 11).

Figure 11 Model of an insulin molecule showing all its atoms.

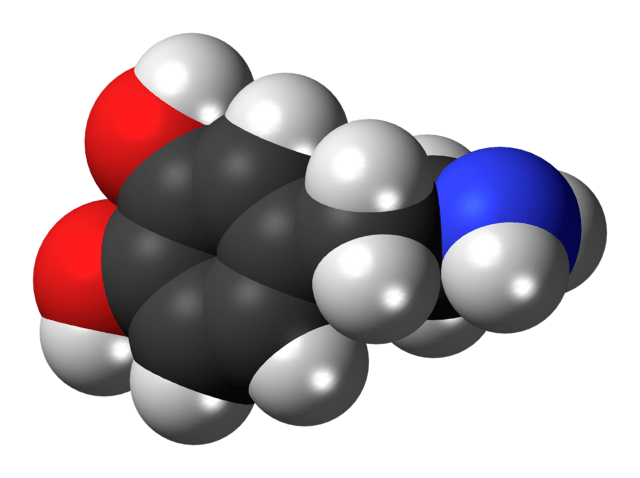

By contrast, dopamine – which transmits signals in the brain and elsewhere – contains just 21 atoms.

Figure 12 Model of a dopamine molecule to the same scale

In popular imagination, hormones are associated with emotional experiences – outbursts of passion or anger or fear, for example – like adrenalin and the ‘fight-or-flight’ response. The signalling role of hormones is not always so dramatic, however. Pangs of hunger, for example are brought about by the hormone grelin, which acts when blood sugar levels fall. A complementary hormone, leptin kicks to signal satiety – the ‘full’ feeling – to the brain, when the stomach has enough to cope with.

An even more gradual hormonal system operates, particularly during childhood and adolescence, to bring about growth. The hypothalamus in the brain sends a ‘releasing hormone’ to the pituitary gland, causing it to secrete ‘growth hormone’ into the bloodstream. Molecules of this hormone are then picked up by various kinds of cells throughout the body, leading them to multiply, thereby increasing the size of bones, muscles and other tissues.

Conclusion

The organs of our body, and their various disorders, are a common topic of conversation – especially as you get older! We are very aware of their roles and potential dysfunction in explaining our feelings of wellbeing or ill health. In this blog we have turned our attention away from these, to a less tangible aspect of our functioning – body systems. These are complex, involving organs, vessels, tissues and intermediate spaces in coordinated and controlled sequences of activity. Systems operate across disparate regions of the body, sending message and materials, from one organ to another. They also, necessarily, include feedback loops that regulate their activity. Just as the thermostat in a room switches off a heating system when the right temperature is reached, so a gland is slowed down when sufficient of the hormone it produces is in circulation.

Other, equally important systems, such as the nervous, immune, digestive and respiratory ones, will have to await a future blog, to be explored. They too have features in common with those described above. They link together processes across separate parts of the body and regulate levels of activity. The purpose of this skate over a selection of key systems has been to pay attention to their common elements and, once again, to marvel at the complexity and fine-tuning of our biological selves.

Andrew Morris 29th May 2024