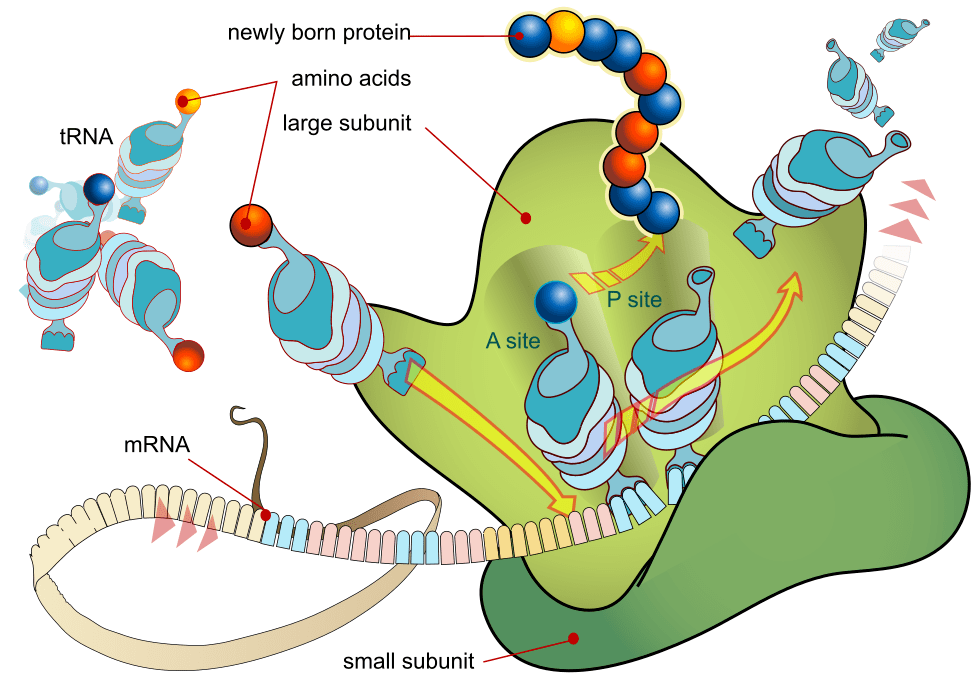

“It’s all bonkers!” – a regular refrain from Julie whenever her discussion group tackles the intricacies of bodily processes. This fiendish diagram illustrates how impossibly complicated basic aspects of science can seem. It depicts the way in which information in our genes gets transcribed into the various proteins that make our bodies tick.

Images such as these abound in textbooks, striking fear in students as they try to memorise words and functions in preparation for exams. It wasn’t such detail, however, that captured the imagination of the discussion group on this occasion. Instead, it was their sheer amazement at the complexity and intricacy of what is really going on in our bodies at the microscopic level. The tiny size of the molecules involved, and the enormous speed at which they act left the group speechless. This sense of wonder or disbelief often follows discussion of the micro level, but it’s equally true at the other end of the spectrum. The unimaginably large size of the universe and its enormous age also stuns people into silence as they try to make sense of the huge numbers involved.

In recognition of this sense of wonder, we explore in this blog, aspects of science that make us consider things off-the-scale; things that are almost impossible to comprehend imaginatively. This sense of awe often has to be skated over in science at school.

Intricacy

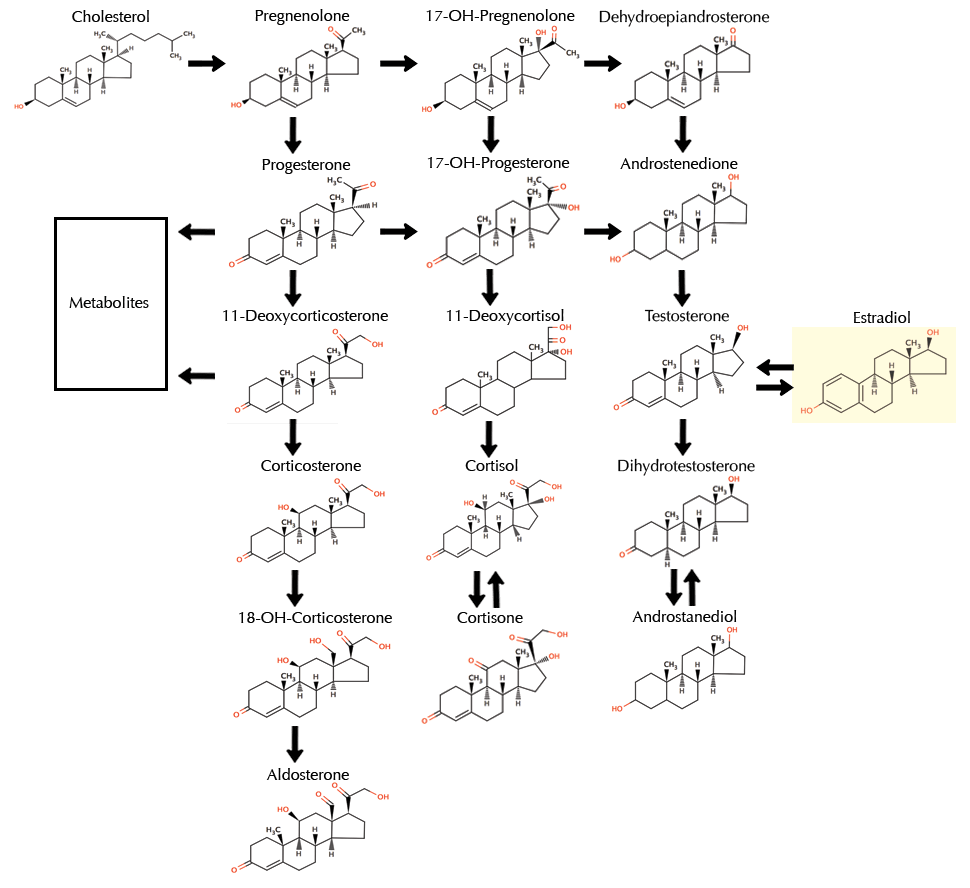

Julie’s comment – “it’s all bonkers” – arose in a discussion about hormones and the menopause. The point under discussion was the remarkable fact that all the main reproductive hormones – testosterone, progesterone and the three versions of oestrogen, are all made in the body from cholesterol. The molecules of each of these compounds are similar to one another, yet the apparently tiny differences in their structure have profound effects on how our bodies work.

The intricacy of the process became apparent when the stages in turning a cholesterol molecule into oestrogen and testosterone ones were illustrated. In a step-by-step sequence, one part of the molecule at a time is altered by the action of specific enzymes, acting as tools – rather like a factory assembly line. Each enzyme works like a pair of scissors breaking a bond in a molecule or, conversely like an adhesive, bonding two bits together – in effect cutting and pasting molecules. The steps in this amazing and beautiful process are indicated in figure 1. The precise detail of names and shapes is not important, it’s the overall pattern that’s relevant. It’s easy to see that each of the hormone molecules in this sequence has a similar structure.

Figure 1 The pathway for producing the reproductive hormones.

The thin lines in each molecule represent the connections between the atoms of which it is made. The thicker arrows indicate each step in the ‘manufacturing’ process. Cholesterol, at the top left is the starting molecule from which all the other hormones depicted are made – from testosterone to oestradiol. ‘Steroid’ is the name given to this class of similar molecules, with their characteristic four-ring structure.

After hearing this story about the origin of the main sex hormones, the discussion group were stunned into a momentary silence. The realisation that this was just one example of the countless complex processes going on all the time, throughout our bodies, was awe-inspiring. Where does this all take place? How frequently? How quickly? How many molecules? How small are they? Myriad questions soon flowed.

Size and pace

Molecules like steroid hormones are classed as small molecules in the body. Although they are considerably bigger than common molecules like water (H2O) or carbon dioxide (CO2) they are much smaller than the giant molecules that make up our bodies – proteins and DNA. They are roughly a millionth of a millimetre across. This unimaginably small size explains how such complex biological processes are accommodated inside the cells of our bodies. Cells are typically a hundredth of a millimetre in size, roughly 10,000 times bigger than a small molecule such as a steroid hormone (though they vary in size). So, there’s plenty of room for all this activity! Like other processes which breakdown or build-up molecules in the body, this all takes place within cells. The speed at which enzymes make or break-up molecules varies enormously, but it is very fast – anything from once a second to ten thousand times per second.

So, the picture we have of microscopic activity in our bodies, is one of tiny, tiny entities –molecules – acting upon each other, within and between larger entities – cells – at incredible speed. These processes digest our food, give us energy, activate our brains and lie behind the functioning of all our organs.

Imagining the very small

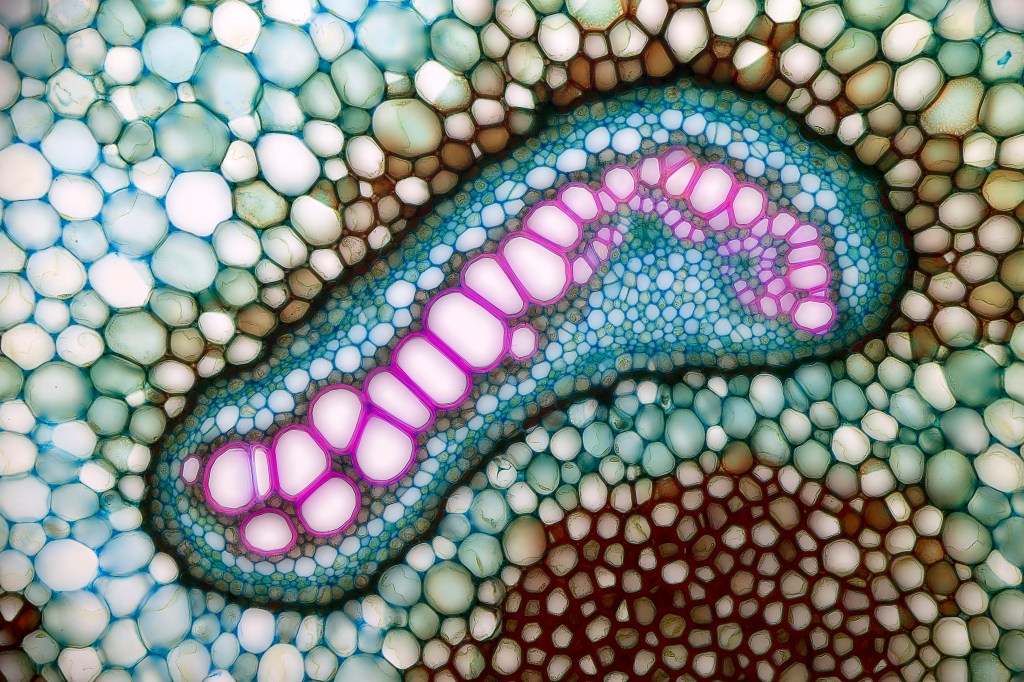

Trying to visualise molecules and cells is almost impossible. I find it hard enough to imagine how a midge, the size of a full stop, manages to fit muscles, gut, eyes, wings and brain, into its minute form – and still manages to bite you. Clearly, our imagination is shaped by the objects we usually encounter – plants, animals, buildings, vehicles – all just a few multiples of our own size. Microscopes on the other hand have enabled scientists to see structure at much smaller scales, down to the interior of cells – and even to molecules. Using such instruments, scientists have developed ways to make sense of this microscopic world, invisible to the rest of us. It’s essential to our understanding of how the body functions and interacts with microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses.

For practical purpose it’s the relative, rather than the absolute, size of things that matters. It helps us understand the hierarchy of structures – what fits inside what.

Figure 2 A photo taken through a microscope, showing several types of cells assembled into a structure (in bracken rhizomes)

We learn that organs, like the heart or liver, are made of tissues, such as muscle and ligaments, and these are in turn made up of cells. Cells are themselves huge complexes of molecules held together in structures that enable the cell to carry out its functions. Molecules themselves are made from atoms tightly bonded together.

There are trillions of cells in a whole human body, and each one might contain thousands or millions of molecules – unimaginable numbers! To cope with such an enormous range of sizes, scientists group together things of roughly similar size using the concept of ‘order of magnitude’. In everyday conversation we talk of “a few thousands” or “in the hundreds” to describe approximate numbers. It helps us distinguish the population of a village from a town or city for example, without having to know precise numbers. Biologists routinely extend this idea downwards, to describe microscopic structures in terms of millimetres, micrometres or even nanometres. To avoid unwieldy numbers like 0.00000000638 they routinely use a simple mathematical device to represent numbers as powers of ten. A millimetre is 10– 3 m; a micrometre 10– 6 m; a nanometre 10– 9 m. The small index number indicates the position of the first digit after the decimal point – e.g. 0.001 is 10 – 3 m. To get a sense of structure and activity at the microscopic level, scientists use mathematical tools of this kind, together with hugely enlarged photographs and diagrams. They get accustomed to dealing with structure at the very small scale in this way, despite it’s being, in effect, unimaginable.

Imagining the very large

A comparable issue also occurs at the opposite end of the range – dealing with huge distances and sizes. The amazing advances in telescope technology in recent times have led to an explosion of interest in the stars, the universe and our local Sun and planets. Today we are able to see extraordinary images of huge galaxies far, far away, thanks to telescopes we’ve sent into orbit, beyond the clouds and dust of our atmosphere. By peering so deep into the universe, these images give us information about its enormous size and distant origin; this takes us into the realm of unimaginably large numbers.

Figure 3 shows a composite image of our local galaxy, the Milky Way, estimated to contain 100–400 billion stars. One of these is our Sun which lies some 27,000 ‘light-years’ from the centre of the galaxy. That means it takes light twenty-seven thousand years to reach us from the centre of the Milky Way. And light travels extremely fast: 300,000 kilometres each second! And this is just within our local galaxy! Even more difficult to comprehend are the distances and sizes of the galaxies hundreds of millions of light years away revealed by the latest James Webb Telescope. What are we to make of these unimaginable distances and the extreme speed at which light travels?

Again, as ordinary citizens, we can only stand back in awe at the magnitude of these things; with our human-scale grasp of size and pace, we can’t intuitively make sense of such figures. For astronomers however, being able to estimate relative sizes and distances is of fundamental importance. It enables the position of stars and galaxies to be established in relation to one another, giving us a picture of the structure of the universe. By combining this with information about the speed at which galaxies are moving, the history of the universe can be traced back to its earliest moments.

Much as biologists cope with extreme numbers by using the concept of ‘orders of magnitude’ to distinguish the micro from the nano, so astronomers use powers of ten to rank huge distances. The more familiar prefixes, ‘kilo’ (thousands or 10 3) and mega (millions or 106) are complemented at this scale by giga (109) and tera (1012). Astronomers use such mathematical representations, alongside vastly expanded photographs of tiny sections of the night sky to make sense of the unimaginably large scope of the universe. Like biologists in the micro world, they also need to identify structures and relate them to one another, even though the quantities involved are beyond imagining.

Action at a distance

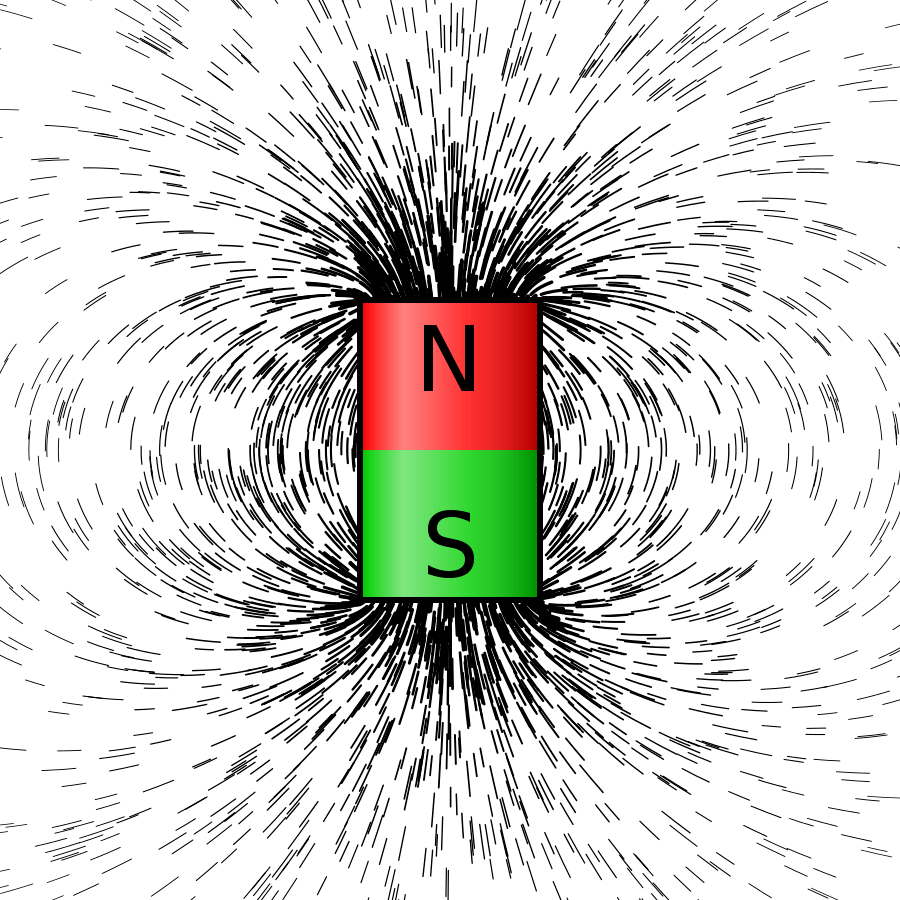

It’s not only extraordinary large, small or fast things that leave us reeling in wonder when we learn about science. A major issue that troubled Helen, in a discussion about gravity, had also troubled me, when I first learned about magnetism at school: how can one thing affect another if they are not in contact?

She was mystified by how gravity enabled the Earth to hold the Moon in orbit when there’s nothing in between to connect them; in a similar way I couldn’t see why bits of iron were drawn magically into lines around a magnet. What was in the space around the Earth or the magnet making this happen?

Figure 4 iron filings surrounding a magnet — giving an impression of a magnetic field

In later life, I was pleased to discover that Helen and I were in good company: this enigma – known as ‘action at a distance’ – has troubled thinkers for centuries. Isaac Newton had been able to show that the Moon rotating around the Earth was experiencing a force of attraction just as an apple, falling to earth was. Not only did he have this remarkable unifying insight, but he was also able to define the force in mathematical form, showing that it depended on the mass of the objects involved. An amazing achievement, which continues to be taught throughout the world, and to direct space travel to this day.

What troubled Helen however was not the mathematical formulation, but the essential nature of gravity; what actually is it that is causing the Earth to pull on the orbiting Moon or a falling apple? There is no connecting rod, just empty space in between. The question made me realise that the awkwardness I had felt, when asking about this at school, had never been resolved. I must have simply agreed to learn the mathematical formulation I was given, and to remember it for exams. My teacher at the time avoided this philosophical quandary, by moving on rapidly and introducing a new concept: the “field”. At the time, this seemed a bit of a cop-out – just replacing one baffling concept with another.

Helen was justified in her sense of awe about the nature of gravity; how else can one respond to the ineffable! Newton himself, had no clear explanation of what gravity actually was, in essence. He thought it must be one of God’s gifts or perhaps due to some immaterial aether existing in empty space or (or both).

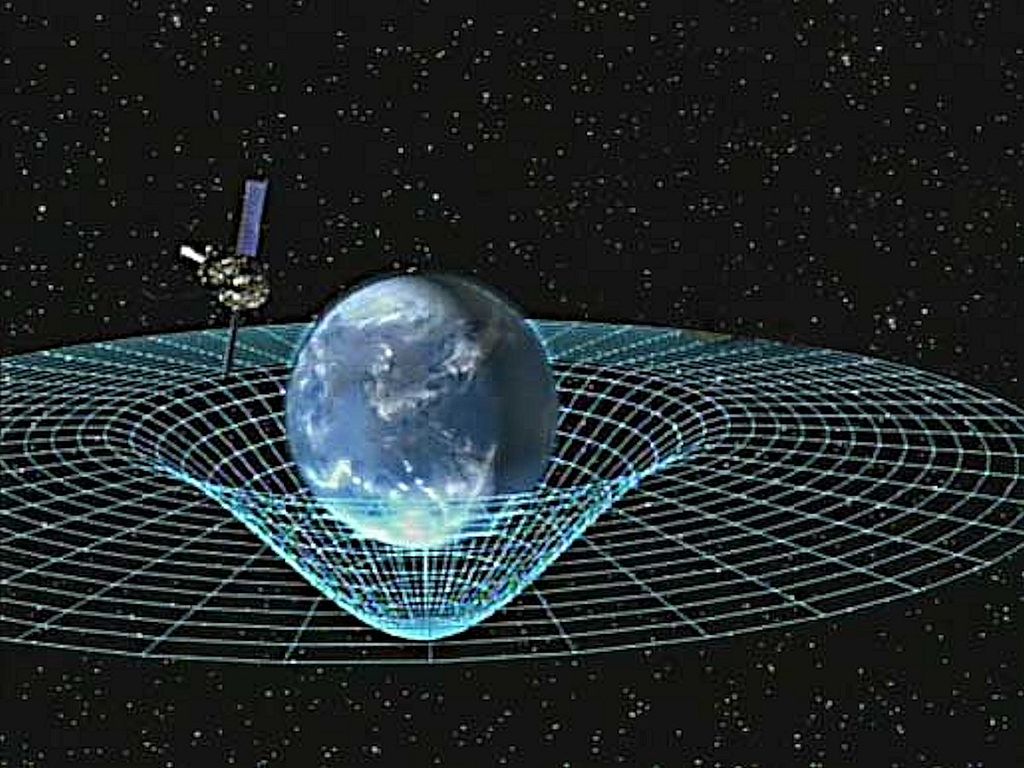

Einstein tackled gravity in a different way. His theory explains the motion of the Moon and any other celestial body or satellite, as simply the path followed naturally because the very space in which things move is curved (strictly speaking it’s ‘spacetime’ – an amalgam of space and time).

Figure 5 orbiting satellite following curvature of space

The Moon, or any other satellite, moves around the Earth, not because of a force of attraction, but because the mass of the Earth makes the space around itself curved, causing satellites and the Moon to orbit like a ball trapped in a roulette wheel (figure 5)

Einstein’s model, however, was not the way gravitational force was explained in my day at school. Instead, the remarkably simple but powerful concept of a ‘field’ was introduced. This idea, developed in the mid-nineteenth century, simply uses the metaphor of a field to denote a zone of influence around an object. Around a magnet is a magnetic field; around an electrically charged object, an electrical field; around a large mass like the Earth (or strictly speaking, any mass), a gravitational field.

The strength of the field depends on the strength of the magnet, or mass or electric charge that is causing it. This tapers off as you move away from the source, and, strictly speaking, extends forever. The ‘zone of influence’ simply means that, were another magnet to be placed in the magnetic field, it would experience a magnetic force; similarly, a mass in a gravitational field or an electric charge in an electric field, experience a force. Theories were rapidly developed during the 18th and 19th centuries, enabling these forces to be calculated precisely. These immensely useful concepts have been taught ever since and used continually in creating the modern technological world in which we live.

These concepts of field and curved space failed to satisfy Helen however, in her quest to understand gravity. Although they may be the basis for calculations about gravity, they didn’t seem to answer the fundamental question of what it is. They only tell us what it does. Facing up to this challenge, forces us to think about the very nature of scientific explanation itself.

We have come to accept concepts such as gravity as scientific ‘facts’ – as definite as the falling apple; but it would be more accurate to describe them as models or theories – created by human ingenuity. Concepts in science are often built around metaphors drawn from other aspects of life, such as a ‘field’ or a ‘wave’. These become accepted if they prove accurate and reliable in describing processes and enable useful predictions to be made. This is of enormous value for practical purposes – producing machines, making buildings and growing crops, for example – but it doesn’t help us understand more profoundly what things actually are in essence. For this we have to look beyond physical explanation (‘meta’ physics, in Greek:). For some this means philosophy, for others, religious belief or mysticism. Science today is content with a humbler role: its job is to design and conduct experiments and make careful observations so that theories and models can be tested rigorously. Successful ones endure and enter into everyday culture and language as ‘facts’; others are rejected or wither away over time.

Conclusion

Over the centuries, scientific discoveries have taken us further and further from objects at the human scale, to which we become accustomed through experience. Once, a grain of sand stood at the small end of known sizes and a mountain at the large end. Since then, scientific observations and experiments have shown just how limited this range is, in relation to all that actually exists in the universe. Microscopes, telescopes and atom-smashing machines have revealed structures trillions of times smaller than a grain of sand (quarks) and billions of trillions of times larger (galaxies).

Of course, such numbers can’t be truly visualised, but, as this blog has illustrated, they can be used to work out what fits inside what, to reveal structure. Thus, atoms make up molecules and these form the substances that make our bodies (and all other living things) tick. Atoms and molecules also make up the stuff of the universe – the hydrogen that fuels our Sun and other stars, and the galaxies in which stars are born. But as we push further in trying to understand fundamentals, we are forced to realise the limits of scientific explanation. In the end, theories are built up and models developed to explain what is observed. Science does just this; at the same time, it leaves plenty of room for philosophers and religious thinkers to get on with speculating about underlying essences: the meaning of life, the universe and everything.

Andrew Morris 15th April 2024

If you have time, one further example of the unimaginable – the ultimate nature of matter- is offered below.

Read More

What is matter?

Throughout history, philosophers and later, scientists, have been driven to ask what matter is actually made of. In ancient Greece, theories abounded – one held that material things were made of combinations of earth, air, fire and water; another, that all matter was made of simple irreducible particles called atoms. Subsequent experimentation and measurement have revised these ideas and revealed many levels of sub-structure beneath the material we ordinarily encounter. Today’s concept of the nature of matter begins, at the bottom end, with extraordinarily tiny particles called quarks, grouped together to make up the nucleus of atoms. Atoms bind together to form molecules and minerals; these assemble in turn to from the structures that make up our world, physical and biological.

Today we are bound to ask about the nature of these most fundamental of particles – the quarks? Will they be found not to be fundamental, after all, just as atoms once were? It seems the answer simply isn’t known. Their discovery in the 1960s was unexpected. Powerful colliders were needed to break up the nuclei of atoms to reveal the underlying quarks. It takes such huge machines such as the CERN collider to do this because the nuclei of atoms are held together by extremely powerful forces. To try to break apart a quark would require much greater power than is available today, so it remains an open question whether they are finally, the absolute fundamental particles or whether they themselves can be broken down into something even more fundamental. Today’s theorists even consider it questionable whether ‘particle’ is an appropriate metaphor at this level; they think of matter at this profound level in terms of ‘ripples’ or ‘waves’ in infinite ‘fields’ spanning the universe

. What this means for our quest to understand ultimate reality is not clear. After all, what, in essence, is a field – magnetic, gravitational or even quarkish?