With terrible scenes of violence in Gaza and an ongoing war in Ukraine, discussion in one science group turned recently to the question of aggression. With combatants and civilians on all sides suffering, what causes human beings to engage in such extreme violence?

Introduction

The study of war is mainly a matter for the humanities and social sciences. Historians, and political scientists chart the history of warfare and analyse the causes and consequences of conflicts. Power, territory, resources, religion – all part of the descent into violence. More recently, the natural sciences have begun adding something to our understanding, through studies of human evolution, physiology and neuroscience. Questions in the discussion group focussed on both what drives us to violence as individuals, and what causes this to escalate to aggression in whole populations.

Helen wondered whether testosterone plays a role in aggression – “males tend to commit more violent crimes” she observed. She could see that “aggression provides a biological advantage if you are defending against predators. We accept that a lion must kill its prey”. Wendy had read about “a basic part of the brain” being involved. “How do the different parts of the brain interact” to keep us balanced, she added. Helen had heard that the “basic part of the brain is still there in us, but we are overloaded with morality and consciousness”. Jean pointed out that “it’s systems rather than individuals that cause mass violence …. and people don’t react rationally within systems – just look at the response to climate change”.

Helen reflected on our bodily experiences: “we are affected by what we are – our glands and hormones – we get sugar rushes and react to temperature and hunger”. “Yes” added Patrick “but other animals are driven by hormones too …. to feed and reproduce – but do we see any other species going to war? Are humans unique in using gratuitous violence?”

The brain and violence

The brain comprises billions of cells linked together in networks (or circuits or pathways), subject to influences from hormones and other body chemicals. Within the brain there are, in the words of the US Society of Neuroscience, circuits of rage. These are part of the brain’s mechanism for dealing with threats and are, as Helen had recalled, buried deep in the more ancient part of the brain.

The so-called ‘attack area’ is in a region called the hypothalamus which is also associated with the regulation of sex, thirst, and hunger, amongst other things. Experiments with male mice show neurons in this region being activated in bouts of aggression. A cat, artificially stimulated in the ‘attack area’ in a laboratory experiment “leaped viscously towards me, claws unsheathed, fangs bared, hissing and spitting”, in the words of the researcher.

Figure 1 Hypothalamus (in red)

The link between violence and maleness is clear across human cultures and also in other primate species.

In ordinary circumstances the potential for defensive aggression is modulated by control systems within another part of the brain – the prefrontal cortex. This region is associated with moderating urges affecting social behaviour and with dealing with conflicting thoughts, among other things. Brain scans of violence-prone people show this region to be shrunken and less active than the norm. Under certain conditions, however, this balancing process fails, for example in cases of road rage.

Figure 2 Pre-frontal cortex (in red)

As Helen surmised in the discussion, hormones like testosterone play a vital part in influencing brain activity. Hormones are molecules that circulate throughout the body affecting the activity of both neurons in the brain and tissues such as muscles. Testosterone in particular is involved in stimulating brain circuits associated with anger and violence and in activating muscles in response. The hormone is present in women as well as men, but at about one tenth the amount. Levels of the hormone are found to be higher in prisoners who have committed violent crimes and in the more aggressive moments in sports. The moderating influence of the pre-frontal cortex is brought about through another hormone, cortisol, which helps control impulsive tendencies. A third hormone, serotonin, acts with cortisol to reduce the effects of testosterone. Studies show that increased testosterone levels reduce sensitivity to punishment, leading to greater fearlessness in aggression. Higher levels of cortisol, on the other hand, are associated with ‘flight’ rather than ‘fight’ in stressful situations.

In evolutionary terms, use of aggression to secure food and defend offspring from attack clearly lent an advantage when supplies were short or predators present. Those genes that contributed to appropriately regulated aggression would have been passed on in greater numbers in those individuals that survived longest and, as a result, produced more offspring. The genetic information for the hormones, neural circuits and associated physical attributes would have been conserved through the generations down to our time, largely unaltered. Slow evolutionary adaptation doesn’t keep pace with the rapidity of change in human culture. As a result, biological systems, appropriate for early human existence remain with us, ill-suited as they are to the pressure of today’s world. In today’s world a minor transgression by a thoughtless cyclist can drive a motorist to rage, overpowering the moderating effect of their pre-frontal cortex.

Ideology

At this point, Helen was struggling. How do occurrences like road rage, located in the bodies of individuals, connect with the mass brutality we see in war crimes? Patrick recalled that some people committing acts of terror see themselves as martyrs in a glorious cause and are willing to die for it. Terrorists on hi-jacked planes are a case in point. Helen wondered about the role of ideology, recalling a phrase from Dorothy L. Sayers: ‘ideologies kill people’. “What exactly is ideology?” Patrick queried.

The term originates with the Enlightenment, denoting a rational system of ideas designed to combat irrational impulses. It was taken up in the nineteenth century to describe economic, political, or religious theories and today sometimes has a pejorative connotation. It is not a clearly defined concept. Recent research in the humanities and social sciences refers to “systems of political thinking … through which individuals and groups construct an understanding of the political world they …. inhabit, and then act on that understanding”. Some scholars see its purpose as instrumental – “tools for political mobilization, legitimation of policies and coordination of action”; others perceive it as a “structure for public discourse, institutionalized norms, and organizational routines – focussing expectations and creating pressures to conform”.

Just as there is no single explanation of what ideologies are for, so theories differ about the human desire for them. One psychological theory understands it as a wish for consistency in our thinking, to protect ourselves from uncertainties and contradictions. A sociological approach emphasises their role in “justifying particular social arrangements ….. and systems of inequality”

What is common to most ideologies, however we understand their purpose and attractiveness, is their dependence on leaders and followers. The question of how leaders use ideology and why others choose to follow them became the focus of discussion in the group. Helen expressed the idea that suppressed hatreds, lying latent within individuals, can get released by a leader who articulates them.

Research in social psychology throws light on this, suggesting that our beliefs tend to get reinforced when we are surrounded by people who have similar beliefs. This kind of social influence could have been advantageous for our early human ancestors; in a potentially threatening world, being aware of how other people are behaving would be helpful. Following others would have helped people avoid poisonous foods or dangerous locations, for example. Imitating the way other people think and act can simplify decision-making, helping us navigate our way in a complex world. For better or worse, these tendencies remain with us today, endowed as we are with much the same physiology as our ancient ancestors.

Other psychological tendencies enable individuals to delude themselves about their actions. As the psychologist Steven Pinker puts it: people can “edit their beliefs to make their actions seem justifiable …. euphemisms, such as ‘collateral damage’ alter the way an action is construed … gradualism enables a slide into barbarism in baby steps … responsibility can be displaced, as in ‘I was only following orders’”.

Leaders are, of course, central to the way our social and economic worlds are structured. Ordinarily they don’t indulge in major acts of aggression. In some cases, however, they do, and the effect on the world can be catastrophic. What is it that distinguishes such individuals?

A study at the University of Warwick business school considers factors that enable destructive leaders to emerge. It shows how they may start out as agreeable and conscientious initially but change as a result of changes in the environment or support group or simply because of their personality. Study of dozens of destructive leaders from history reveals corruption as a key indicator of violence. Extremely destructive political leaders often espouse distinctive and powerful ideologies and foster exceptional levels of violence. Compared to non-violent ideological leaders, they showed a narcissistic sense of entitlement, authoritarian attitudes, and a distrust of information, related to fear and uncertainty about outcomes. The author of this study adds that “groups that have become isolated … have unusual potential for violence … and may be vulnerable to the emergence of violent leaders and more willing to act on their direction”. Clearly, the combination of groups of vulnerable people craving a simplifying system of beliefs, plus extreme narcissistic individuals seeking to stamp out uncertainties in complex situations, makes for a dangerous world. With such potential for self-destructive actions, it may seem odd that our species, Homo sapiens, has managed to survive so long. Not only has it survived, of course, but it’s adapted its way of life to fit almost every ecological niche on the planet. By contrast, most species appear to have evolved in relation to one specific environment or another: a particular climate or source of food, for example.

Fugure 3 Examples of adaptation to specific environments

What has enabled Homo sapiens to adapt so flexibly and spread itself across the globe?

Cooperation

This question exercises scientists in anthropology, archaeology and evolutionary biology and has spawned a variety of theories. An article in Scientific American suggests that two particular innovations, unique to Homo sapiens, endowed the species with its capacity to prosper in so many environments. The first was its development of more advanced weapons that could be thrown – like spears and darts – thanks to the thinking and manipulative capacities of an enlarged brain. It’s easy to see how this offered an advantage in the competitive struggle for food and other scarce resources. The second capacity, however, is less obvious: the capacity for cooperation with individuals outside the family group – i.e. people who did not share – and therefore seek to pass on – a particular set of genes. According to this theory, it was the combination of these two exceptional capacities that enabled Homo sapiens to work together and so improve their hunting success.

The scientist Frans de Waal studies cooperative behaviour in primates. He has found that they co-operate widely with each other, not just with their relatives. The activity is often mutual, and when an individual helps another, the act is remembered. For example, when watermelons were given to a few lucky chimpanzees in an experiment, they tended to share with those that had groomed them earlier. Sometimes co-operation may even be motivated by empathy – caring for one another; chimpanzees have been seen to adopt orphans.

De Waal considers our ancestors were simply too small and vulnerable to have beaten dangerous animals in combat. He suggests we owe our success as a species more to our cooperativeness than our capacity for violence. It is only humans that work together in large, hierarchically arranged groups, to undertake major tasks and to feel responsibility to one another.

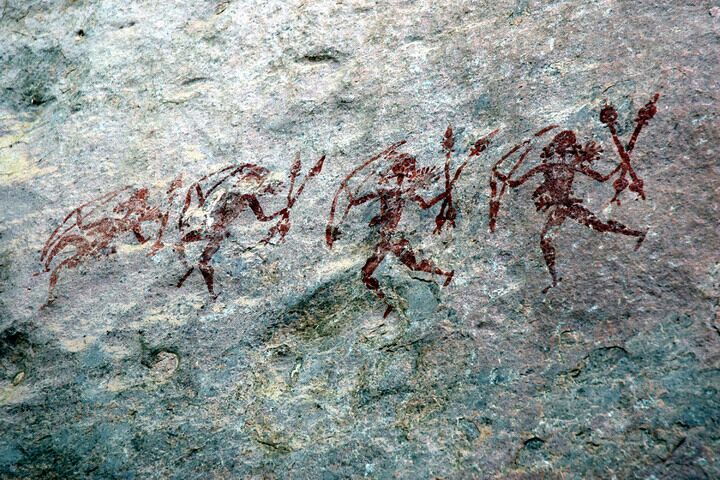

FIgure 4 Cooperation in hunting (cave painting from hoshangabad, India)

This kind of cooperative behaviour may have evolved partly from hunting and gathering activity, but also from the care of babies and infants. Evolutionary change comes about by the spreading of favourable genes. Whichever genes increase the chances of babies surviving will appear more abundantly in subsequent generations than genes of those that never made it. Those genes that carry the code for hormones and neural networks associated with baby care will gradually become dominant. It is suggested that, over evolutionary time, these processes gradually extended beyond maternity care to bonding and empathy more generally, stimulating co-operative behaviour across communities.

Cooperative behaviour is observed in a wide range of species. Research at the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California demonstrates how essential cooperative behaviour is to communities: ants organise three-lane traffic systems as they hunt for food; ‘cleaner’ fish swim into the mouths of bigger ones to eat bacteria and parasites; spotted flycatchers screech out loudly to warn their fellows of larger birds of prey. Human cooperation, the research observes, “never means the absence of conflicts of interest; it means a set of rules for negotiating them in a way that resolves them.”

In the utterly different field of ‘Game theory’, computer scenarios simulate social behaviour by manipulating incentives, rewards and punishments in different scenarios. Research based on this, published by the Royal Society in London, concludes that “our fairness-based cooperation consists in calculating the costs paid by others in cooperating, whatever they may be, and reimbursing them by cooperating back in any way we can”. The researchers speculate that it’s thanks to our unique cognitive skills that humans will invest into their environments because of shared interests rather than simply consuming it in the competition for resources, as other species tend to. Clearly, this evolved tendency is being severely tested across the globe today.

Conclusion

A sense of despair prevailed in the group discussion on which this blog is based. Appalling aggression and military destruction were playing out in the Gaza strip; war was continuing in the Ukraine and under-reported violence was continuing in many parts of the third world. Almost all thoughts were of compassion for those suffering, and of concern that some kind of a way out of conflict should be found.

In the context of a science discussion, this backdrop led to questions about what drives us as individual towards violent behaviour and how in larger groups this can lead into serious levels of aggression. Many sciences contribute to enquiry of this kind: archaeology, anthropology, neuroscience, endocrinology and social psychology, for example. Taken together, these fields of research give us a sense that, as individuals, we humans live out our lives poised between opposing tendencies: on the one hand to compete and use aggression to defend ourselves or gain personal advantage; on the other to cooperate for the greater good. Under everyday conditions in modern societies, this balance works in favour of large-scale and widespread collaboration. In more extreme conditions it can tip in favour of our atavistic tendencies to violence.

© Andrew Morris 26th November 2023