In a discussion group, Amy, a mother-to-be, was wondering why a new baby might look like their dad or their mum – or even someone further back in the family tree. After exploring how genes from the two parents get combined in the process of fertilisation, discussion turned to what happens next. How does a fertilised egg develop into an embryo? Amy wondered “how specialised cells know which part to the body they belong to”. Marion mentioned her grandson who was getting very tall. “How does the body know when to stop growing?” she asked. “What keeps things in proportion as they grow” added Julie. Sarah recalled a phrase she’d heard on a science radio programme: “It used to be all about the gene, now it’s all about the cell”.

How organisms grow and develop their specialised organs is a fascinating and highly active area of research in what is known as ‘developmental biology’. It looks into how cells multiply, how they specialise to form each particular organ and, most importantly, how they start and finish at the right moment. Sarah was right – it’s all about cells.

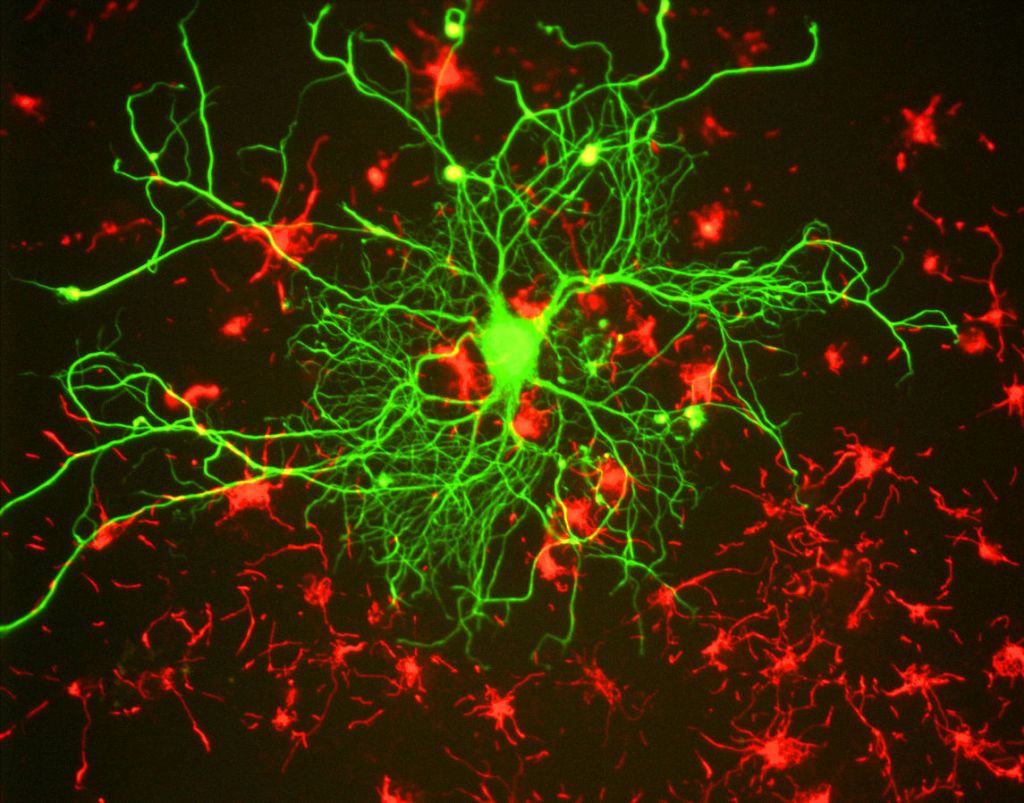

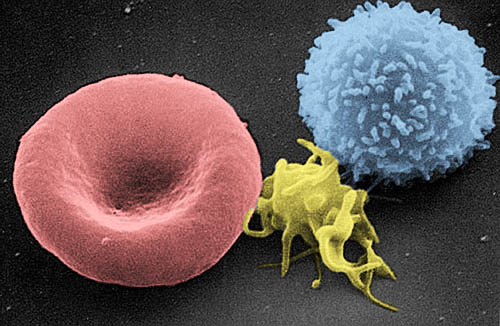

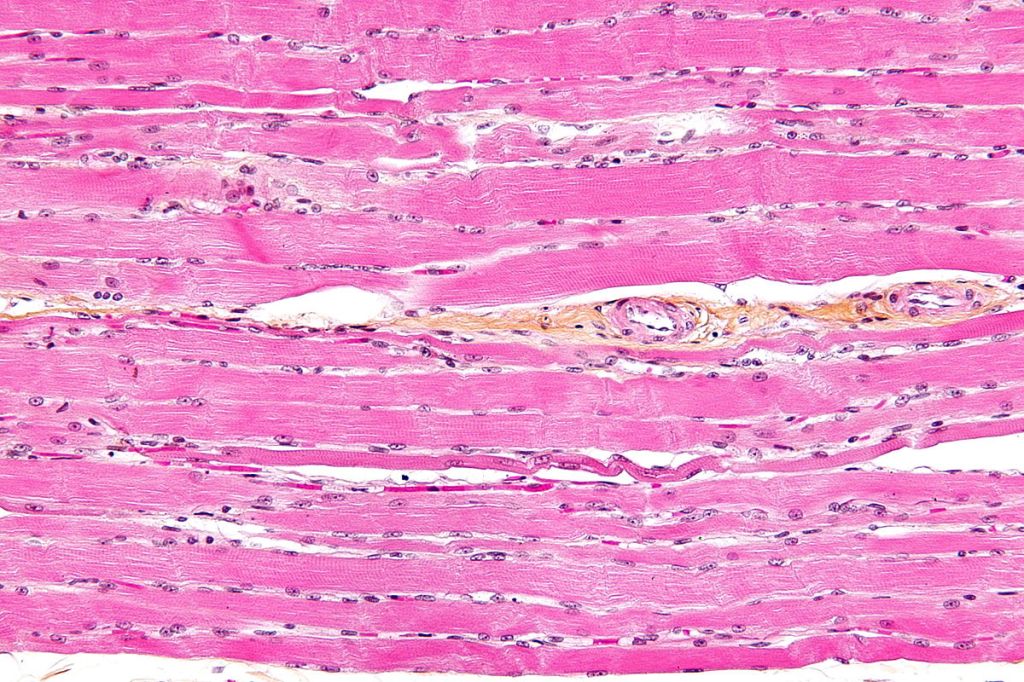

As a reminder, cells are relatively large entities in the range of tiny things of which the body is composed. They have a complex architecture, made up of a large number of discrete parts, known collectively as organelles – little organs – each with its own distinctive function. As in a town or city, the many diverse structures inside a cell look and behave in different ways, but they interact together to make the whole system work. A previous blog gives some insight into this: Very small and very busy: inside the cell. Cells vary in size. On average they are 10 – 100 micrometres across; about ten would fit across the width of a human hair. The also vary radically in shape. Nerve cells are an extreme case, having a very elongated arm projecting out of the main body (called an axon) which may reach centimetres or even metres – to reach the distant parts of your body. The variety of form and function is hardly surprising, given the widely varying task they have to perform – from carrying oxygen in your bloodstream to tensing up and relaxing your heart muscles. Figures 1, 2 and 3 are examples:

| Figure 1 Nerve cell (green) Figure 2 three kinds of blood cell Figure 3 muscle cells |

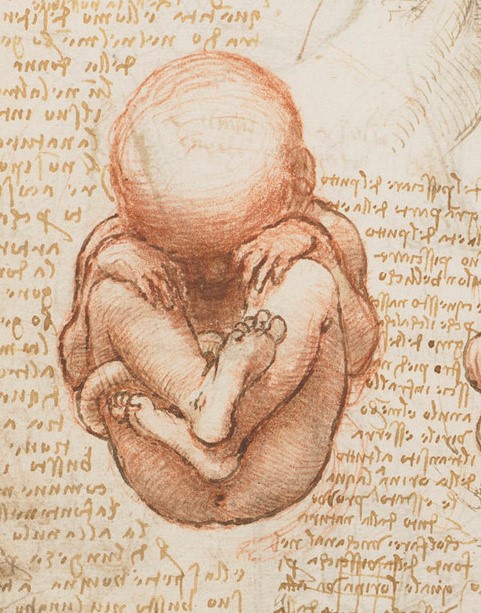

But our very first cell – the fertilised egg – is a beautiful spherical shape with one overwhelmingly urgent task before it: to reproduce itself. That’s how all cells are created – out of pre-existing ones; they are not put together from scratch. To produce a new cell, an old one must divide. In this way, the vital information about what a cell has to do, locked up in its DNA, gets transferred from one generation of cells to the next. After dividing, the two cells that result are identical to each other, and contain the same DNA and cell components. This process, in which cells divide and replicate themselves, is common to the growth of the embryo, of the growing child and the adult in need of repair and maintenance.

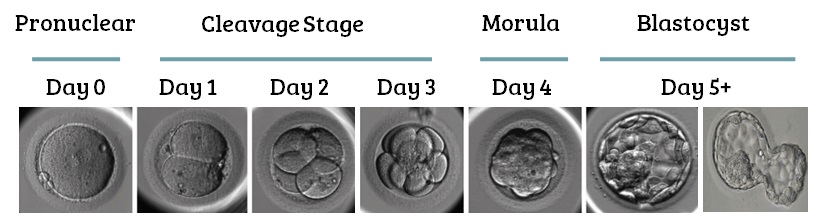

In the case of the very first generations of cells that go to make up an embryo, the two second generation cells each duplicate themselves, producing four; these then multiply to produce eight, then sixteen and so on. Soon the origin cell has given rise to a ball of approximately one hundred cells, known as a blastocyst (see figure 4).

Figure 4 first days of embryonic growth. Image credit: Sean at remembryo

The cells organise into two kinds: an inner group that will go on to form the embryo and an outer group that will develop into the placenta. The inner group of cells are unspecialised at this stage and are capable of specialising into any kind of cell later on. This ability will only last for a few days. The outer group of cells will go on to produce a sac of amniotic fluid to surround the growing embryo and a yolk sac to provide an initial source of nutriments.

After one week the ball of cells, attaches itself to the wall of the uterus and is firmly implanted in it a few days later. It’s difficulties at this implantation stage that may mean several cycles are required before pregnancy occurs. Hormones are now secreted and it’s these that are detected in a urine test for pregnancy.

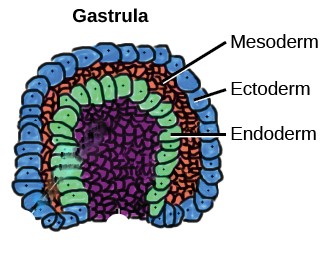

At three weeks the inner group of cells that will form the embryo develops into a three-layered, disc-like structure Figure 5). Cells in the outer layer (ectoderm) begin a journey of increasing specialisation which will, after many generations of dividing, form the outer parts of the body: the skin, sensory organs, hair, and nails. The middle layer cells (mesoderm) will ultimately become the core of the body: skeleton, muscles, connective tissue, heart, blood vessels, and kidneys. The inner layer (endoderm) will go on to form the inner lining of the guts, liver, pancreas, and lungs – the soft and delicate ‘epithelial’ tissue.

| Figure 5 Three layers of cells. Image credit: Abigail Pyne (adapted) |

How amazing that the three great zones of our bodies:

- the central organs, bones and muscles

- the skin, hair and nails

- the internal lining of our guts

are already separated out into just three layers of cells at this very early stage. Soon, cells begin to form the elements of nerve tissue and the spine; by eight weeks the rudimentary structure of all the organs has been established.

The first cells created from the original fertilised egg – and several generations after them – are called stem cells, indicating that they are capable of developing into a specialised cell of any kind -muscle, nerve, liver… whatever. Each of their genes is available for use in the next generation of cells. After division and multiplication, however, the descendants of these cells become specialised, taking up a particular role in the developing tissue. In the earliest stages of development, they specialise to form the three distinct layers of the early embryo, mentioned above, and also the tissue for the emerging placenta and amniotic sac. As the organs begin to develop, cells become ever more specialised, contributing to the formation of the various tissues that will go to make up our muscles, nerves, liver and so on.

At this point in one discussion, Amy asked a simple question: “how do cells know where to go? How do cells know when to be part of an arm and when part of a hand or finger?” “Yes” added Julie “and how do they become specialised so they can be to become part of the skin or heart or brain?” These questions take us further into the fascinating field of developmental biology.

Development

As we have seen above, cells divide, growing exponentially in number – 2 4 8 16 32 ….. – as an embryo develops from the fertilised egg, into a ball of cells, then the three layers which will form the outer, middle and inner zones of our bodies. The transition from a simple group of cells into a specific type of tissue and then a particular organ, involves two essential changes. Cells have to aggregate together in the right positions to be part of, say, a nerve or a liver, and they need to specialise to be useful in that role (a process known as ‘differentiation’). Many factors are involved in these complex processes, and research is actively studying them in a great variety of animals and plants.

Cells cling together to form part of a tissue by means of a specific class of proteins known as cadherins (presumably because they help cells adhere). These molecules project out of the surface of cells and lock onto complementary proteins on neighbouring cells.

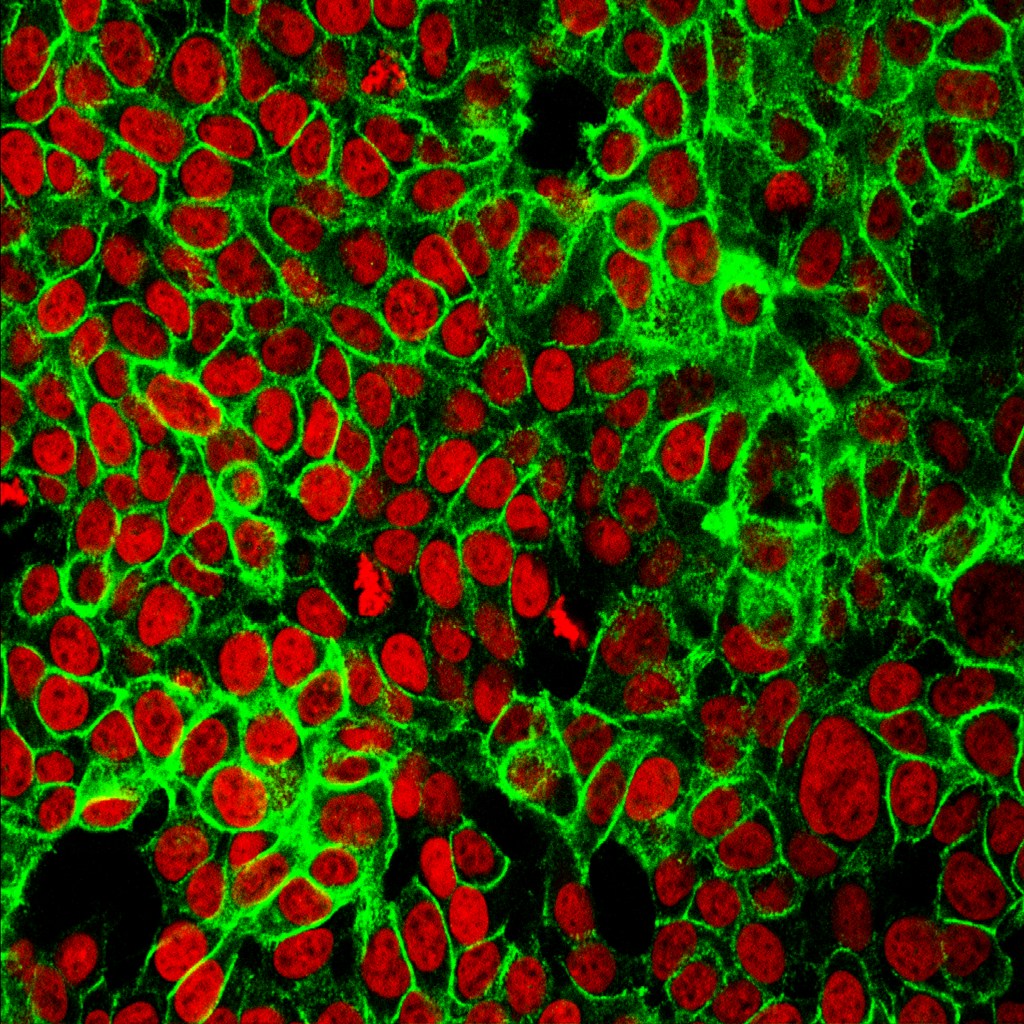

Figure 6 is photograph of cells with their nuclei stained red and cadherin molecules sticking them to each other, in green.

These cells are from human colon cancer. Studying the behaviour of cadherin in cancer cells is especially important because, if the adhesion weakens, cells may detach and migrate, spreading the cancer.

Figure 6 cells (red) surrounded by cadherin molecules (green)

An animation, a little way down on this website, shows cadherin molecules acting rather like Velcro.

As they group together to form a tissue, cells need to position themselves relative to one another so that the tissue, and the organ of which it is part, have the right form and functionality. An eyeball needs to be spherical and translucent, and a tendon long and thin, after all. Various mechanisms seem to be involved and are being actively studied in chicks, Zebra fish, nematode worms, fruit flies and other species. An important mechanism that enables cells to position themselves, involves the secretion of special signalling chemicals from specific cells. These chemicals spread out around the cell, getting less and less abundant the further away they are – just like an aroma getting weaker the further it is from the source. As the concentration of the chemical lessens steadily from the source we imagine it like a ‘gradient’ – an imaginary downward slope from the source. The cells in the neighbourhood of this source of chemicals respond to the concentration of the chemical in their locality and, in this way, are sensitive to where they lie on the gradient. The weaker the local concentration, the further they must be from the source. It’s like being able to judge how far away you are from someone wearing a fragrant perfume.

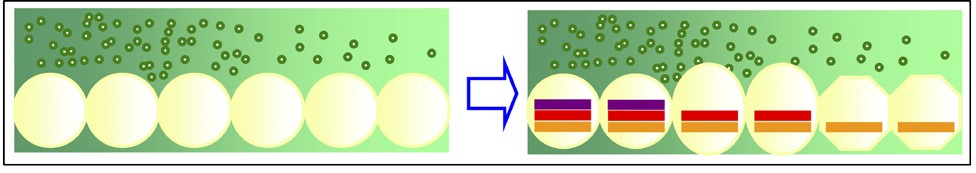

Figure 7 (left hand side) illustrates the process with a series of cells (yellow) in a row. Molecules (green circles) released at the left-hand end diffuses along the row getting weaker towards the right. What an ingenious way of knowing where you are!

Figure 7 Cells (yellow) in a concentration gradient of positioning molecules (green)

Image credit: Marta Ibanes in Molecular Systems Biology (Creative Commons attribution)

The position of a cell in a gradient may also play a role in determining its fate. As an embryo develops, successive generations of dividing cells become positioned in such a way as to elongate, thin out or fold tissue in preparation for a more specialised future as part of the skin, muscle or circulatory system, for example. As well as moving into these distinctive positions relative to one another, cells become specialised in preparation for their future functions. In this process, known as differentiation, cells cease being able to make use of every one of their genes: they become selective.

Differentiation

It seems quite extraordinary, but the entire complement of genes that our bodies need to carry out all their functions, are present in every single cell. Packed into the tiny nucleus of each cell (about one hundredth of a millimetre across) is the extremely long, thin thread of DNA containing all our genes (apart from a few more in a different organelle). Human DNA is approximately 2 metres long and contains 20 – 25,000 genes, coiled up tightly in the tiny space of the nucleus. But, as you might imagine, each particular type of cell needs to use only some genes, not all of them. For example, a gene containing the code to make an enzyme that breaks down alcohol is expressed in a liver cell but not in a neuron. Similarly, a gene that contains the information needed to make a neurotransmitter molecule for the nervous system, is expressed in a neuron but not in a liver cell.

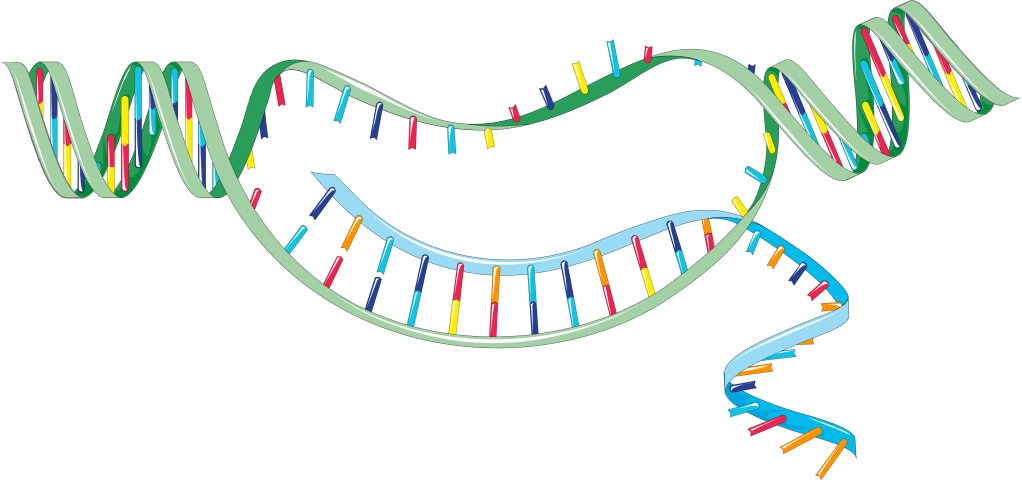

It would be impossibly cumbersome, and quite unnecessary, for the code in every gene in the double helix of DNA to be “read off” in every cell. DNA is wound-up tightly, so much of its length is likely to be inaccessible. Figure 8 shows how an accessible gene gets “read off”. A short length of the lengthy DNA double helix becomes temporarily unwound; the two strands (green ribbons) are separated for a stretch, enabling a short length of code to be ‘read off’.

Each link in the double helix (in red, yellow, dark blue and light blue) is a specific chemical, which acts as a ‘letter’ in the DNA code (the four letters A C G T denoting the four chemicals). The sequence of ‘letters’ of the code are transferred to a single stranded molecule called RNA (in blue).

Figure 8 Cells (yellow) in a concentration gradient of positioning molecules (green)

Image credit: Marta Ibanes in Molecular Systems Biology (Creative Commons attribution)

The RNA molecule moves away from the DNA, carrying the transcribed code to a place where proteins are made, based on the code. Each gene (or stretch of DNA) carries the code for one specific type of protein.

The way in which cells are instructed to specialise in one way or another is a highly fascinating and active area of research today. They have to develop from the general ‘stem’ type in the early embryo into the great array of cell-types that enable a full-grown body to function: stretching muscles, fighting infection or sending messages along the nerves. Research is showing that the way a cell operates is altered by special signalling molecules that pass from one cell to the next.

One class of such molecules, known as ‘transcription factors’, switches on or off particular genes in the receiving cell. The right-hand side of the diagram in Figure 7 above shows genes being gradually switched off in cells further from the source of a ‘transcription factor’. The three coloured bars represent three different genes – all are switched on towards the left but only one towards the right. The combination of switched-on genes influences the shape and function of each cell. This is how, in the example given above, genes that code for enzymes that break down alcohol get switched on in liver cells, but not in nerve cells.

Conclusion

So, in summary, the organs of our bodies grow and develop to the right size and shape, thanks to various types of molecule that pass between cells, switching on and off the various processes involved in cell division. Many factors influence when these signalling molecules are activated, including patterns inherited via the genes, the rhythm of the hormones and the influence of the environment – diet and stress levels, for example. Trying to answer questions about how the parts of our bodies are formed has taken us on a deep dive into the complex area of developmental biology. It’s led us into an exploration of the way cells and DNA work, much of which has only been discovered in the past few decades. It’s not an easy topic to grasp, but is well worth struggling with, not only because of its intrinsic interest but also because of its importance in understanding big issues of life and death – the growing embryo and the spread of cancer. Once again, by following up questions from everyday life, we have got to grips with some truly fundamental ideas in science.

©Andrew Morris 5th September 2023

To take the topic a step further, the Read More section below follows up a key question Marian put to the discussion group: “My ten-year-old grandson is getting very tall. How does the body know when to stop growing?”

Read More

Stopping growing

When we think of the extraordinary variety of animal species there are and have been, it’s remarkable how closely related their basic structures are: ‘heads, bodies and tails’, in the common phrase? This uniformity of overall design suggests to biologists that patterns of growth must be in-built. A few forms of life, such as slime moulds, by contrast, just grow and grow haphazardly, without any in-built plan.

Research on animals as diverse as fruit flies and zebra fish suggests that genes inherited from parents influence how an organ – or indeed the whole body – grows (and stops growing). Indeed, it’s part of our everyday knowledge that tall or short stature tends to run in families. The genes we inherit play a big part by carrying the code for hormones that promote or restrict growth; but other kinds of chemical also contribute by signalling from one cell to the next when growth should accelerate or come to a halt. Mechanical forces also exert an influence on bodily growth, as cells get stretched and compressed as they come together to form organs. Growth is clearly a complex process of regulation; understanding the mechanisms of control is clearly of vital importance, not least because failures in control lie behind the growth of tumours and ultimately of cancer.

Growing taller

Marion’s question about her grandchildren leads us into one area of research that is already relatively well understood: the height of children and teenagers. We’ve seen how tissues grow by the multiplication of cells, and organs acquire their size and shape by chemical signalling between cells. We now consider how the overall growth of our bodies is promoted at different periods of our lives. Key to this global level of regulation is the action of hormones; in particular human growth hormone. Its role is to stimulate cell reproduction and regeneration. This hormone is released after the brain signals to a gland in the neck (the pituitary) to secrete a releasing hormone. It happens especially strongly shortly after the onset of sleep and peaks, as you might expect, during adolescence.

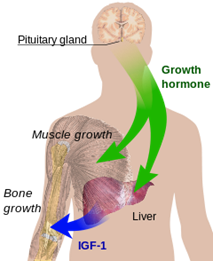

The role of hormones in general is to travel from their place of origin to other places where they have their effects. They are messengers, travelling around the body through the bloodstream and other channels. Growth hormone stimulates certain cells to multiply and stimulates the liver to produce another hormone (IGF-1 in Figure 9) to help.

Figure 9 hormones that influence growth

Growth is never faster that in the embryo; it peaks around the fourth month of pregnancy. The rate then decreases rapidly until the age of four or five when it remains fairly steady until adolescence. It then accelerates markedly for a few years.

As we know from experience, children grow to different heights, even within the same family. The average height of many populations has been increasing over the years with improving health: by 11 cms over the last century in the UK, and 5-6 cms in the USA. In some sub-Saharan countries, however, it has been decreasing in recent decades. Clearly, diet affects the ultimate height a person reaches; exercise, medical conditions and stress have also been shown to be factors. But the major factor, accounting for between 60% and 80% of the difference in average height, is the set of genes you inherit.

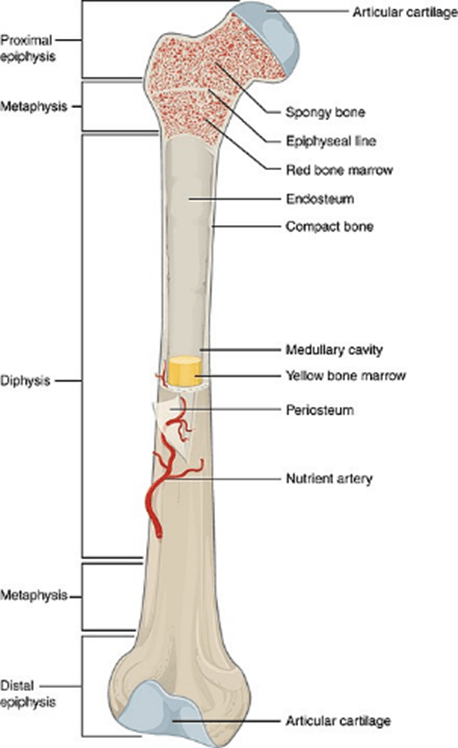

Bones begin to develop in the embryo from around eight weeks and continue to grow in length until around the age of twenty-five. We think of them as hard, almost inorganic parts of our bodies, but, like all other organs, they too are made of cells. In the tough outer part of the bone the cells are embedded in a so-called ‘matrix’ comprising mainly a mixture of collagen (a type of protein) and a crystalline component based on calcium and phosphate minerals. Bone cells first produce the material of the matrix, then become trapped inside it. Collagen fibres give a bone tensile strength, while the crystalline minerals in it resist compression. Together these ensure that our bodies are capable of both stretching, when we run for example, and holding firm when we push or carry a load. The interior of bone contains the softer tissue of the marrow which is fed by embedded blood vessels. It is here that most of our blood cells, red and white (and platelets), are made.

Figure 10 the parts of a long bone

Bone tissue develops initially in the embryo. Flat bones like the skull develop out of connective tissue and long bones out of cartilage. The process of ‘ossification’ that turns this into hard bone continues throughout our early life and is mostly completed by 18 to 25 years of age. Thereafter, the process is called upon to a lesser extent as our aging bones require maintenance and repair.

©Andrew Morris 5th September 2023