“It’s the sense of community, of shared values” asserted Linda, referring to the popularity of the Burning Man festival in California. “Lots of people focussing their consciousness on one thing” added Sarah, an American using Zoom to participate in the discussion. Why do we love large groups so much? What makes us social? What makes parents bond so tightly to their babies?

A flood of questions followed about what makes us tick, what makes us feel happy.

Happiness across the world

As it happens, happiness has become a significant area of research in recent years. Perhaps it’s a reaction to the sense that happiness doesn’t seem to be rising with increasing prosperity; perhaps it’s the rise in the incidence of mental distress. Whatever the cause we can at least rejoice that science is turning its attention to this most central of human concerns. It’s a fascinating mix of biological research on hormones and the brain, psychological studies of moods and emotions and global surveys of how people feel.

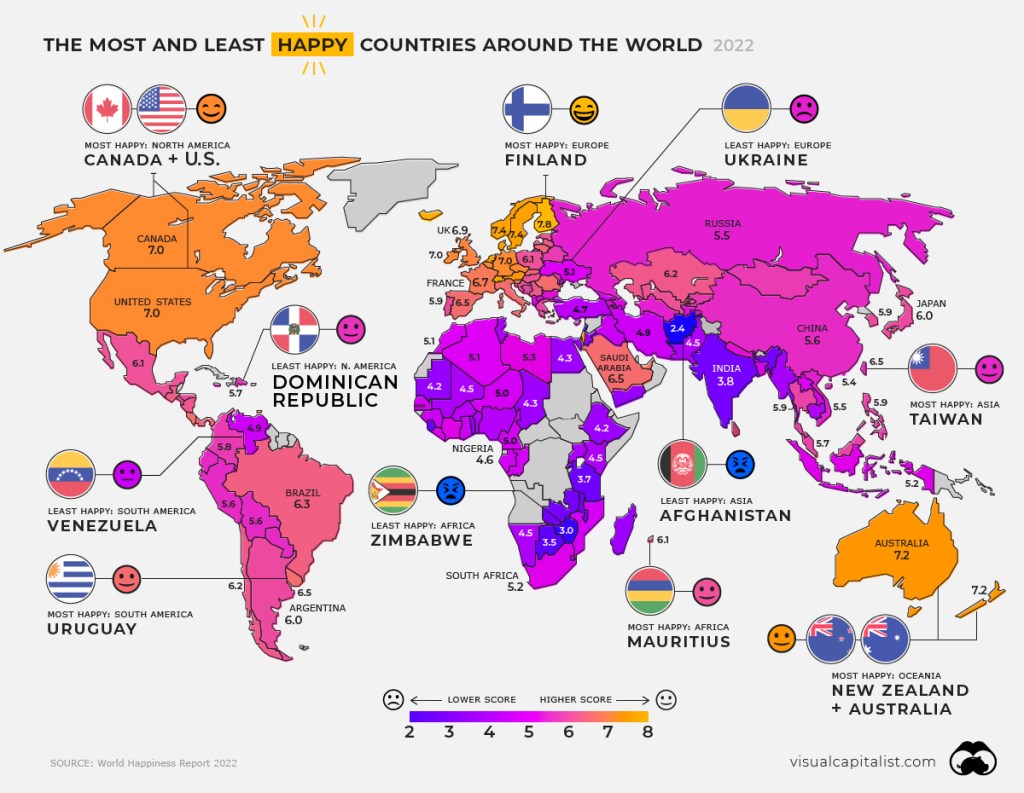

Every year a major international study of happiness levels is undertaken across the world, as part of a global initiative for the United Nations. Its 2023 report shows, somewhat surprisingly, that “despite several overlapping crises, most populations around the world continue to be remarkably resilient, with global life satisfaction averages in the COVID-19 years, 2020-2022, just as high as those in the pre-pandemic years”. However, there are important differences between the top and the bottom halves of the population. Although there are exceptions, people are generally happier in countries where the “happiness gap” is smaller.

It also shows that “acts of kindness have been shown to both lead to, and stem from, greater happiness. Everyday kindness, such as helping a stranger, donating to charity or volunteering, are above pre-pandemic levels”. Emotional resilience is remarkably strong: “even during these difficult years, positive emotions have remained twice as prevalent as negative ones, and feelings of positive social support, twice as strong as those of loneliness.”

An earlier study compares happiness levels with average income in different countries. It shows that above a threshold level, average income doesn’t affect levels of happiness. However, for poorer countries below this threshold, there is a link between happiness and average income. The message is that extra income helps raise levels of wellbeing for those closer to poverty, but not for those who are already reasonably well-off.

What makes us happy?

The idea that there is more to happiness than pleasure (or wealth) alone is not new. The ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, considered that a well-lived life (he called it eudaimonia) also contributed – roughly what we might call meaningfulness today. Feelings of commitment and participation in life are also considered by some psychologists to be important factors today. Historically, ideas about what constitutes happiness have changed with the times. In some eras it was related more to virtue than pleasure, in others to religious faith, in others to the balance of pleasure over pain.

People who research happiness today often use the concept of ‘subjective wellbeing’ as a measure – how individuals themselves rate their feelings. Three principal components of happiness have emerged from this kind of research:

- satisfaction with one’s life – work, health, marriage etc,

- positive emotions and moods

- low levels of negative emotion.

In 2011 the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan sponsored a resolution which was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations inviting national governments to “give more importance to happiness and well-being in determining how to achieve and measure social and economic development.” The resulting World Happiness Report, published each year, reflects growing international interest in measuring levels of happiness as well as productivity.

Based on self-assessment by people around the world, this reveals that over 80 percent rate their overall eudaimonic life satisfaction (meaningfulness) as “pretty to very happy”. A similar percentage rate their current hedonic mood (pleasure) as positive – above the mid-point on a scale. These figures hold even for people living with clear disadvantages. A review of research on happiness in 2008 reinforces this rather positive finding by concluding: “most people report being happy most of the time. Humans appear to have a predisposition to mild levels of happiness”.

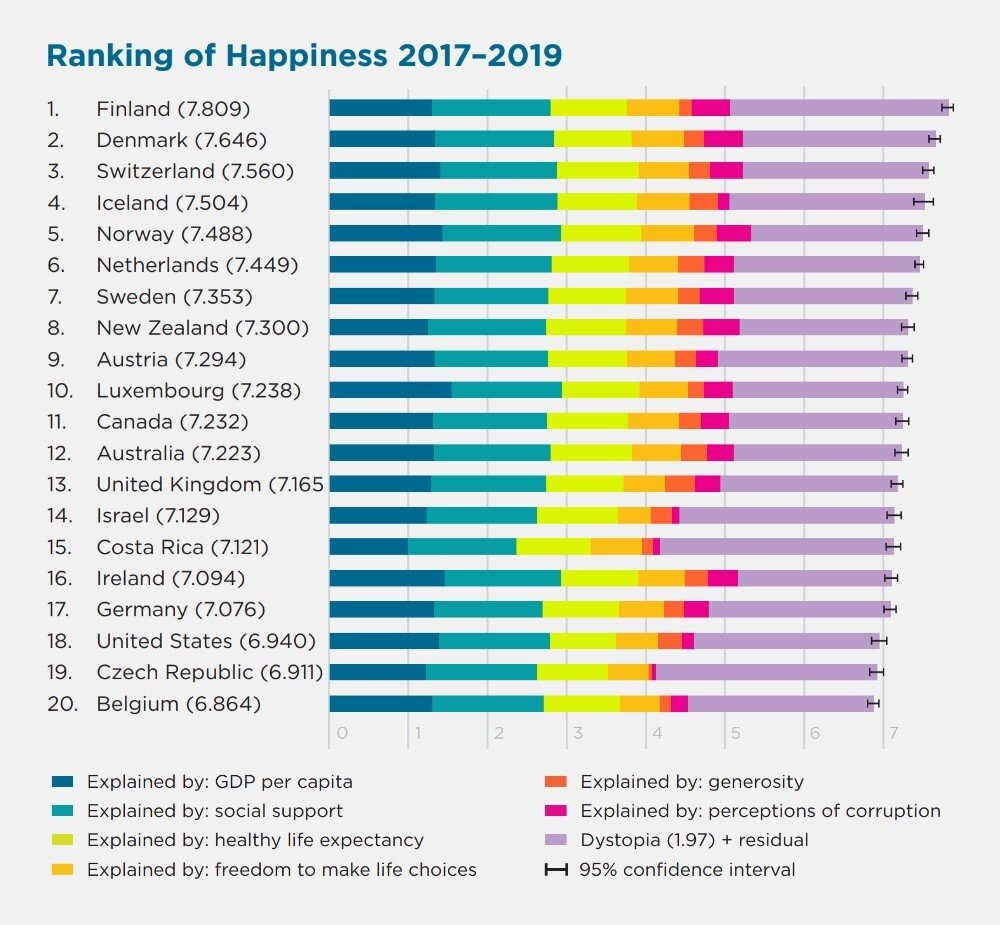

Figure 1 World rankings of happiness in 2022

Of course, levels of happiness vary enormously between individuals and, for each individual, over time. The values quoted in world rankings are averaged over large samples. Differences are also found between differing national cultures. An analysis of the world happiness rankings shows that, across nations, people’s sense of satisfaction with life experience is linked twice as strongly to their experience of positive emotions compared to negative ones – i.e. the route to greater happiness and life satisfaction is mainly through increasing positive emotions, rather than minimising negative ones.

In nations with a more individualistic culture people seem to be particularly sensitive to negative emotions when they report on their state of happiness. Perhaps this reflects the emphasis placed on the individuals feeling good and doing well in such societies. If negative feelings are felt to be unwelcome, bad experiences can have a big impact on whether a person feels unhappy. In nations with a more collective culture, on the other hand, feelings associated with self-criticism and suffering may get more of an airing, making negative feelings seem more acceptable – they are more likely to lead to sympathy and compassion. Having negative experiences would then have less impact on one’s judgement about happiness.

The chart in Figure 3 lists the top twenty happiest countries. It identifies the extent to which levels of happiness can be explained by specific factors such as health and wealth. Clearly, income, social support, health and freedom are major factors in almost all countries. (The extreme right bar in mauve – “dystopia” – can be ignored; it’s a technical device designed to make all countries comparable).

Figure 2 World rankings of happiness averaged over three years.

Why Finland?

Finland has topped this chart for six years in a row. “What puts Finland at the top of the happiness chart and keeps it there, year in, year out?” was the obvious question put by Patrick in a discussion. The Finnish government points out that the World Survey measures overall contentedness with life, rather than momentary pleasure. It relates its high rating to its “infrastructure of happiness”, common to Nordic countries, in which social systems “support democratic governance and human rights, not to mention free education and healthcare”. A Finnish professor who researches well-being comments on a particular characteristic of Finnish people: “when you know what is enough, you are happy.” The Finnish word sisu seems to capture it: “grim determination in the face of hardships” – reflecting an expectation to persevere, without complaining. Others mention the prevalence of music, the arts, sport and abundant nature as important factors.

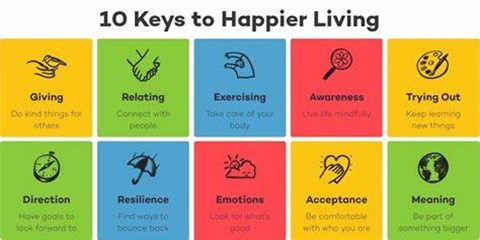

Keys to happiness A key contributor to the organisation behind the World Happiness Report, is the UK economist Richard Layard. He is a founder of the UK movement Action for Happiness, whose mission is to help people create a happier world, with a culture that prioritises happiness and kindness. It has invested heavily in analysing research about happiness, from which it has developed ten keys to happier living.

Figure 3 Themes from Action for Happiness

Most of us are probably aware of the importance of some of these ten themes. Perhaps the most well-known is the importance of physical exercise – underlining the link between physical and mental well. Links with other people and with communities are also widely understood as important to our wellbeing. Scientific studies seem to back up much of what we might pick up anecdotally from our experience of life.

Exercise

Scientific research confirms many of the benefits we expect from exercise for our psychological health and happiness. It helps us manage and treat depression, anxiety and stress as well as boosting our confidence and helping us think better too. Good quality sleep is also important, as is being active for 30 minutes or more on most days. Sitting for long periods each day, over time, can be detrimental; finding ways to stretch, twist, stand up or walk in little moments is helpful. Being outside or near greenery or water is added advantage: we generally feel happier in natural environments than indoors or in those that are built up.

Relating

Research also confirms something we may know from experience: we become happier and healthier through our relationships with others. People that we trust help us feel valued and loved which boosts our wellbeing and resilience, making us less prone to depression. Relationships with friends and family members are important to our sense of happiness, as we might expect, but so too are community relationships with neighbours, work or school mates and hobby enthusiasts.

Emotions

Research at the University of North Carolina shows that experiences of pleasant emotions – even short ones – cause us to be more open and trusting of others, more open to ideas and more likely to adapt. These moments add up over time to build our psychological resources and resilience.

Studies of the brain suggest that evolution fitted us human beings to be particularly aware of dangers, at a time when threats to life were, in general, far greater than today. We still have to contend with this ancient wired-in bias today, because evolutionary change is so slow. This can easily result in undue predominance of negative emotions such as excessive anxiety. Studies show the experience of pleasant emotions can help undo the potential damage in our brains caused by chronic exposure to stress.

Giving

Studies have shown that when we do kind things it can literally give our brain a boost, activating its ‘reward centres’, making us feel good. Scientific studies show that helping others can contribute to our happiness by enabling us to experience more positive emotions and satisfaction with life. This can increase our sense of meaning and boost our self-confidence. It can also help reduce stress and help us feel calmer too. People who volunteer regularly are found to be more hopeful and experience fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Some of the other top tips based on research summarised by Action for Happiness are perhaps less obvious but no less important. Being more aware – or in current terminology “mindful”; being more accepting of ourselves as we are; building up resilience against unhappy influences; developing a sense of direction; seeking meaning in the way we live our lives: all these have been shown to play a part in sustaining our sense of happiness. The evidence from many different trials shows that we can learn skills and ways of thinking that can help to boost and build our resilience and self-regard. Activities such as volunteering, learning, being creative, appreciating nature or practising a faith can give life meaning. Meaning, as well as pleasure, is important for happiness and there are things we can do to foster it.

Neuroscience

Feeling good is an essential part of the reward system that encourages us to take actions that benefit us. Evolution favours behaviour that motivates us to survive to maturity and then to reproduce. The mechanisms that link emotion to behaviour are present in most animals and are similar in many different species today. This suggests they have been selectively preserved throughout evolutionary history because they are of crucial importance.

Research in neuroscience is investigating how different parts of the human brain are involved in different aspects of processing feelings. One area, for example interacts with the stimuli that affect our feelings – things we might see, hear, touch or smell that make us feel happy or motivated (or the reverse). A different region is associated with determining whether we associate positive or negative emotions with any particular stimulus, such as a smell or sound. Yet other regions associate emotion with higher order processes, such as empathy and social behaviour. Interestingly, it appears that pleasures of a more abstract kind, like aesthetic responses and socialising use the same brain mechanisms as more direct sensory pleasures.

However it’s not just the sensation of liking that drives our behaviour. Wanting and learning are also part of the story. We have to be motivated to take actions in our own interest and to acquire knowledge of which ones are helpful and which are damaging.

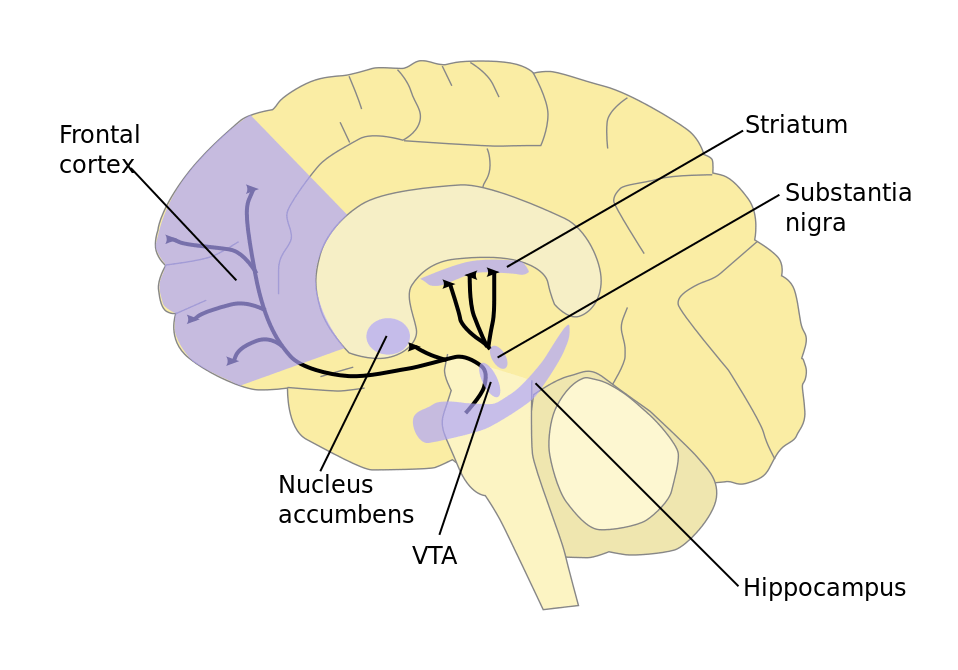

A particular group of neurons, deep inside the brain (called the mesolimbic pathway) is associated with converting a pleasure sensation into a sense of wanting. Dopamine is one of the main brain chemicals involved in activating this pathway.

The diagram in Figure 4 is not intended to be understood in detail. It just shows graphically how our mood is influenced by brain chemicals such as dopamine, moving from one area where they are produced (like the VTA [ventral tegmental area] and substantia nigra) to others where they are released and have their effects (nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex and striatum).

Figure 4. Dopamine pathway in the brain

The sense of ‘wanting’ is produced in the brain in a quite distinct way from the sense of pleasure or ‘liking’. This disjunction helps us understand why it’s possible for us humans to want something badly, without necessarily even liking it – addiction being the extreme example. Exactly how the sensation of pleasure arises in the brain is not fully understood, though research in deep brain stimulation is proving helpful. By inserting a fine wire through a hole in the skull and passing electric pulses through it, pain can be relieved and some symptoms of depression alleviated.

Hormones

Social relationships with other people are known, both through personal experience and from research, to be important factors for happiness. Seeing faces, touching and caressing and thinking about enjoyable relationships are all important triggers for the networks that give rise to feelings of pleasure in the brain. The bonds that bring adults together and keep them bonded and the attachment to infants are obviously extremely important for the survival of the species.

The emerging field of social neuroscience is beginning to study the interaction between parents’ intuitive behaviour towards an infant and the development of the infant’s brain. A particular hormone called oxytocin has been studied extensively in experiments with both animals and humans. It is associated with a range of pro-social behaviours. As well as being involved in sexual activity, childbirth and breastfeeding, it has an important part to play in bonding. In one study, oxytocin levels in the blood rose after petting between humans and dogs and an injection of oxytocin encouraged virgin sheep to show maternal behaviour. Conversely, a drug that opposed oxytocin closed down maternal behaviour when given to female rats. In humans, oxytocin is involved in initiating maternal behaviour and in bonding between member of groups.

Research into what makes us feel happy or otherwise, focuses not only on structures in the brain but also on key brain chemicals. Two of the most important ones that affect our mood are the hormones dopamine and serotonin. Positive mood appears to be associated with increased levels of dopamine in the brain; negative mood, with lower levels. Serotonin levels, also linked to happiness, are found to be reduced in bouts of depression. A major class of anti-depressant drugs acts by stemming the loss of serotonin molecules at the points where brain cells connect to one another (known as a synapses).

A different class of chemicals in the body, called endorphins also play a part in mediating feelings of wellbeing. These molecules are released during many different kinds of behaviour associated with pleasure, including listening to music, eating chocolate, laughter, and having sex. Higher levels tend to inhibit pain and lower levels reduce positive feelings. Endorphins are released during exercise, which helps explain why we tend to feel better after a walk or run.

Another hormone, cortisol, is linked to feelings of depression, stress, and anxiety. Individuals with low levels of cortisol in their saliva give higher ratings for “personal growth” and “purpose in life”, making this measurement a good predictor of happiness. Adrenaline, which increases heart rate in a fight-or-flight response, is also a predictor of happiness.

Clearly, the levels of a variety of distinct hormones affect our behaviour and mood in complex ways. Many differing hormones are involved in the various aspects of our emotional functioning. Understanding this helps us make sense of the great diversity of advice on offer from health experts. This includes, for example: creating a bedtime routine to improve sleep hygiene; taking a walk for exercise; meditating; spending time in nature; engaging in art, dance, yoga or tai chi, practising deep-breathing. All, in their multifarious ways, are recommended as ways to reduce depression and anxiety.

Genetic factors

At this point in one group discussion turned away from brain structure and hormonal effects, to the question of family patterns. Sarah wondered whether the tendency to be generally happy or anxious runs in families – “is there a genetic component to happiness?” she asked.

Questions of heritability like this are often addressed through studying identical twins who have been separated as infants and brought up in different settings to see how differences in upbringing and experience affect people with identical genes. One study, in which twins reported on their well-being, found that many external factors that may at first sight seem relevant – such as socioeconomic status, educational attainment, family income, marital status and religious commitment – only accounted for about 3% of the difference in well-being between twins. Genetic inheritance on the other hand accounted for 44% to 52% of the difference. So, genes are indeed a factor.

A number of genes have been identified associated with happiness, among them one that holds the code for a protein that distributes serotonin in brain cells and therefore leads to mood regulation. There are two versions (or alleles) of this gene. The particular pair of versions you inherit, one from your mother and one from your father, makes a difference. 35% of people with one combination report a high level of satisfaction with life compared to 19% with a different combination. So, there’s a degree of genetic luck in our sense of life satisfaction.

Conclusion

This foray into the science of happiness reminds us that our minds and bodies are not separate things, but aspects of a single entity. The conceptual separation of mind and body, often attributed to the 17th century philosopher René Descartes is considered fundamentally mistaken by many thinkers today. Certainly, there is reliable evidence that particular moods and emotions are associated with measurable levels of specific body chemicals and specific areas of activation in the brain. The cautious phrase “associated with” is repeatedly used in research literature, rather than “caused by”, to remind us that the actual mechanisms that link our feelings to physical actions are not yet fully understood. It’s not always clear whether a high level of a hormone, for example, is the cause of a given mood or the consequence of it – or indeed, simply runs alongside it. Even harder to fathom is the philosophical, or perhaps mystical, question of how we come to experience sensations subjectively – what makes us thrill to the glory of a sunset or melt at the sound of a sweet melody. For these we need to look beyond the limits of the biological and physical sciences!

© Andrew Morris 31st May 2023

You can subscirbe to these blogs by adding your email address below You will then receive a notifcation whenever a new blog appears (roughly monthly)